Babi Yar: Do Not Be Silent, 80 Years Since the Slaughter, Tishrei 5702 (Sept. 1941)

As evening fell, during the night of Yom Kippur 5702, when the voices of those praying rang out of the synagogues with the words “Our Father, our King, we will avenge the blood of Your servants that has been spilled” – the cries of those murdered in Babi Yar had not yet died down, and they mingled with each other.

In the soil of Babi Yar, not only were the murdered buried, but also their story, which was covered up and kept a secret, and the voice of our brothers’ blood cried out from the ground in silence… The account of the murder in Babi Yar raises poignant questions: what did the world know, and the Jewish world in particular? How did Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poem break the silence? What is known about Babi Yar today in Ukraine and what is happening there today?

Researched and written by: Mrs. Devorah Surasky, Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

Babi Yar (literally translated as Grandmother’s Ravine) is a wooded ravine located on the northwestern slopes of the city of Kiev near the Jewish cemetery. The phrase “Babi Yar” is almost synonymous with spilled Jewish blood. The site became one of the prominent symbols of the Holocaust of Russian Jewry. In Kiev, the capital of Ukraine, the Jewish community that was one of the largest and oldest in Ukraine stood out. In the pages of the Jewish history of Kiev, severe pogroms were recorded in the years of 5408 and 5409 (1648-1649) – and not only then, of course. The peak of suffering and persecution came about three hundred years later.

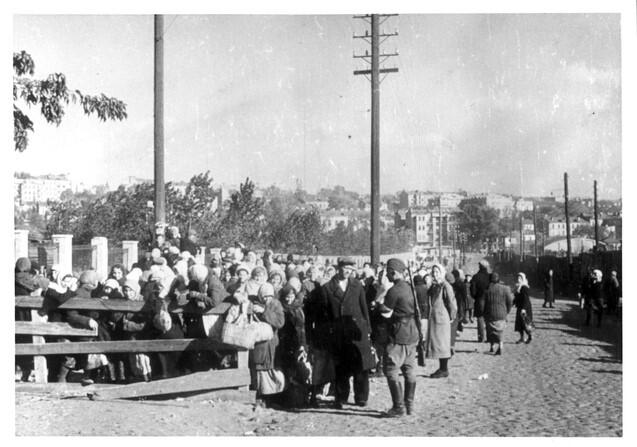

In September 1941, the Germans captured Kiev. The rumours of the Nazi approach led to about 100,000 of the 160,000 to escape into the USSR. A few days after the beginning of the occupation, bombs were dropped in the central streets of the city where the headquarters of the German military government were located. As a result, the Germans suffered losses. The finger of blame was immediately pointed at the Jews, and the officials of the military government decided to eliminate the Jews of Kiev as a result. Later it became known that the NKVD was responsible for the chain of explosions. On September 28, 1941, the 7th of Tishrei, an order was given: “All Jews must report at 8:00 in the morning on Monday, September 29, 1941, at the corner of Malinovski Street […] next to the cemetery. They must take with them documents, money, valuables and warm clothes.”

The wording of the announcement and the instructions for what to bring misled the Jews, who showed up en masse, even though the Germans had already been engaged in the work of extermination since the summer months of 1941. The information was still scarce, and many Jews were tempted to believe the rumours that were flying in the air, such as false information claiming “that the Germans had succeeded in reaching an agreement with the Russians, according to which they would exchange the Jews with German prisoners of war.” There was a whole rumour mill, and the Land of Israel also came up as a possible immigration destination – a German ploy designed to allow the concentration of Jews in one place. Survivors of the community testified about the German deception mechanism in similar ways.

Thousands of Jews obeyed the order and were led to a compound enclosed by a wall and a barbed wire fence, where the Jewish cemetery of Kiev as well as part of the Babi Yar ravine were located. The Jews were brought into the cemetery, placed their valuables in a carriage designated for this (as part of the camouflage policy – “the objects will be sent after you”). They were marched in groups of ten, placed on the edge of the ravine and shot into it. The murderous work was conducted by the Einsatzgruppen, and units of the Ukrainian auxiliary police took part in it. 33,771 Jews were murdered in two days, according to Einsatzgruppen reports. In the months that followed, thousands more Jews were captured and also shot in Babi Yar, including many Jews who managed to hide, and were turned in by their Ukrainian “friends”. The Germans testified after the war that so many whistleblowers arrived – that due to a lack of manpower they could not handle all the inquiries.

Later on, other undesirable elements in the eyes of the Germans were also murdered there: gypsies, mentally ill individuals, and more (in total, about 100,000 people were murdered in Babi Yar).

As part of Operation 1005 (obscuring and hiding the evidence of the murder of the Jews, under the command of Paul Blobel) – in the summer of 1943, prisoners (of which about 100 were Jews) were brought to the place to burn the bodies. About 18 of them managed to escape, after they realized what their fate would be when the job was over. The Nazi camouflage and obscuration was an overwhelming success in Babi Yar. The land maintained its right to remain silent and made an alliance with the murderers. What was heard was only the voice of silence; Babi Yar’s secret was not known.

So what did the world in general, and the Jewish world in particular, know about the events at Babi Yar? From a review of information and documentation files and the press of the time – it seems that not only the Jews of Kiev did not know their future, but the entire Jewish world and the settlement in Israel also knew nothing. Even the global media were caught in this bubble. Admittedly, in 1942 rumours did spread (some of which did not have reliable sources), and the danger of their brothers overseas was felt in the air. Efforts were made to track down any scrap of information – but many reports in real time, or close to it, proved to be unfounded, due to the lack of sources, the secret policies, and the raging war.

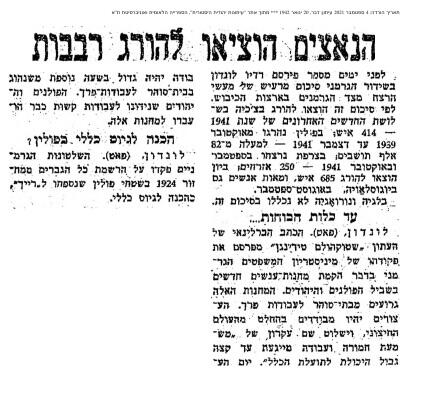

In the press collection of the National Library of Israel, in the newspaper Dvar from January 1942, it states, according to Radio London, news about German murder in the occupied countries (the Jews as murder victims did not appear in the news): “According to this summary, 414 people were executed in Czechoslovakia, in Poland – from October 1939 to December 1941 – over 82,000 inhabitants, in France in September and October 1941 – 250 people were murdered…” These initial data do not reflect even a tiny part of the picture of the loss of the Jews during this period.

The double Holocaust: how did Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poem break the silence?

The silence was not broken, and the Holocaust of the Jews of the USSR remained in darkness even after the war. As part of the Soviet apparatus, the Holocaust of the Jews of the USSR was completely denied and ignored. The word “Jew” was not mentioned in all the descriptions of the war victims, only the words “Soviet citizens”. As part of the trend of hiding information, it is possible to point out the burying of the “Black Book” written by Grossman and Ehrenburg, Jewish writers who served as military correspondents in the Red Army and had gathered information about the murder in Eastern Europe. The book was not published in the Soviet Union. The authorities did not take kindly to emphasizing the suffering of the Jews over other elements. Beyond that, the authorities had difficulty internalizing the amount of cooperation of the Soviet population with the Nazis.

Despite the hiding of information, the silencing, the disregarding, and the blurring – among the survivors there was a feeling of “With your blood, live,” and the memory was alive, cutting and painful. Babi Yar became a center for Jewish pilgrimage. On Tisha B’av or Yom Kippur they would come there, offer a prayer, and commune with their relatives. Yom Kippur became the day of remembrance for Babi Yar and, in general, the day of Holocaust remembrance among the Jews of the USSR, who would come in large numbers to synagogues to remember. The authorities did everything in their power to prevent the Jews from going to Babi Yar, with tricks and claims such as “the road leading to it needs renovation.”

In the 1960s, during the reign of Khrushchev, who promoted de-Stalinization policies, the demand for the commemoration of Nazi crimes in Babi Yar increased. Among the people who demanded this was the Jewish writer Ehrenburg. The attempts met with an impenetrable wall, and not only that – but the sadistic denial increased and even broke records in 1961, when the town of Kiev decided to build a recreational park on the site. All protests were to no avail.

Mrs. Batya Barg, from Kiev, who lost six of her brothers in Babi Yar, described in her book “A Voice is Heard in the Silence”: “I got on the streetcar going to the Podil residential quarter in Kyiv. The streetcar flew through the neighborhood, and every time my heart was pinched anew from passing through this place where six of my brothers were massacred. The streetcar just passed the suburban neighborhood and entered the city, and a tremendous noise reached my ears, like that of an earthquake or a waterfall. When I got home, it became clear that a few minutes after the tram in which I was traveling passed, a huge cloudburst occured in the Babi Yar area. This caused the drift of huge amounts of mud, which was mixed with human bones, a landslide that covered the entire lower part of Kiev and buried thousands of people under it… not only the Jews, but also the common people in the population declared that this was the revenge of the murdered” (S.Z. Sonnenfeld, A Voice is Heard in the Silence, pg. 157).

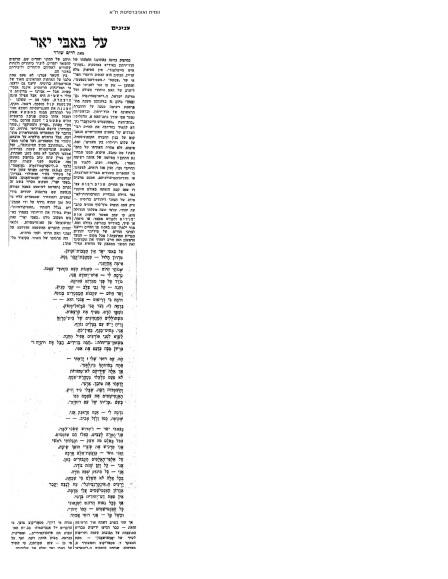

This disaster was called the “Kiev mudslide” – the collapse of the dam placed on the Babi Yar ravine. About 1500 people perished in this disaster. The disaster caused the topic of Babi Yar to break into the consciousness of the population. But the most prominent catalyst for the awakening of the discourse about the murder of the Jews in the USSR and the Soviet silence in the face of the injustice – was undoubtedly the poem by the popular Russian writer Yevgeny Yevtushenko that was published at the time and opens with the words:

“No monument nor gravestone stands at Babi Yar

A drop sheer – as a crude gravestone”

In this pioneering work, the tragedy of the Jews of the USSR was brought up, and a voice of protest was raised against the silencing, the denial, and the mechanism of obscuration; about the cruelty, not only at the time of the massacre, but in the prolonged ignoring of the suffering of the Jewish people in the Russian collective memory. It was published in September 1961, on the twentieth anniversary of the murder of Babi Yar , in “Litaturnaya Gazeta”, a major literary weekly. The poem struck millions of readers with astonishment, most of whom encountered this horror for the first time. The echoes of the poem spread even outside the Iron Curtain. In the Israeli press of the time, we notice the documentation and monitoring of the distribution of the poem, its influence and its metamorphosis. The discourse on Soviet Russian antisemitism and its relationship to the Jews and the State of Israel was put on the agenda. The publication of the poem and its effects raised questions and perhaps hope in this regard. And thus we can see in an article in the Dvar newspaper from September 29, 1961, in which H. Shorer wrote on Yevtushenko and the poem: “…expresses in his poem his experiences of standing at the bloody place ‘Babi Yar,’ and his shock at antisemitism. I wish the words would have an impact on the masses of the Russian people and the peoples of the USSR. Before the list saw the light of day, news arrived of harsh and sharp reactions from the critic… who claims that the comments about antsemitism in the Soviet Union are provocative… We have high hopes that the poem about Babi Yar will fulfill its mission.”

The story of the poem gained momentum after the famous composer Dmitri Shostakovich read the piece and decided to set it to music. Many affairs were bound in the name of the poet and the poem got a platform thanks to him.

The Soviet authorities did not sympathize, to say the least, with the mood created by the printing of the song, and “asked” to change the poem, “and make it less Jewish”, after a short concert tour. News about this appears in the press of the time. In January 1963, a news item appeared in the newspaper Al HaMishmar titled “Yevtushenko fixed Babi Yar”.

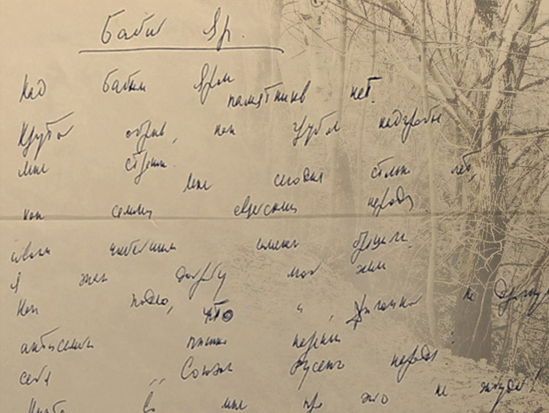

News from the Maariv newspaper, on January 1, 1969, reveals to us new information: “The original manuscirpt of Babi Yar was deposited in the National Library”. It turns out that the official version was preceded by a preliminary version, but Yevtushenko was afraid to publish it due to the Russian censorship. The manuscript arrived in 1968 at the National Library, and is in the National Library’s collections. The information about how it arrived and its whereabouts is still shrouded in fog. It is known to have been purchased by Mr. Leo Graham and deposited in the National Library.

(The original manuscript of Babi Yar, the National Library of Israel)

From a recreational park to a museum – what is known today in the Ukraine and what is going on now in Babi Yar?

The pressure to build a monument bore fruit: in 1966 a competition to see who would construct the monument was held between architects. The monument was completed in 1974. But still – the voice of the dead was not heard. The monument that was erected was in memory of all the victims. It was not until 1991 that a monument was placed in memory of the Jewish victims, and in April 2021 the synagogue in Babi Yar was inaugurated. In current times, the government of Ukraine announced the establishment of a museum complex that will commemorate and give over the events at Babi Yar and document the untold story.

How do we, the Nation that Remembers, remember and commemorate Babi Yar and the martyrs of the Holocaust?

The Jewish duty of remembrance and commemoration.

As a matter of fact, the Jewish memory is shaped by the Jewish-Torah oriented reflection: “Do for those slaughtered for Your Oneness”, which Jews have beseeched for thousands of years. The sages gave us tools for memory and for understanding what the meaning of memory on a Jewish historical platform.

Babi Yar’s story is the story of one of tens or perhaps hundreds of murder sites that are both known and unknown to us. Each site is a witness to a vibrant Jewish life, to people who walked there, and each of these people had a face and a name, a family and a community, a part in Jewish heritage. We remember each of them like the Temple of G-d. Many acts of remembrance and commemoration were initiated by the survivors – whether it was the building of graves, whether it was the recitation of the Kaddish, memorial gatherings, commemorative plaques in synagogues, recitation of chapters of the Mishna, printing holy books, and establishing synagogues and communities.

With the German invasion of the USSR in the spring of 1941, the great slaughter began in the USSR and its annexed territories: in Russia, Ukraine and its provinces, Lithuania and its Baltic sisters, Belarus, Eastern Poland and more, and one after the other in the midst of the killing sprees there were mass instances of the sanctification of G-d’s Name. Ida Pinkert, one of the few remaining survivors of Babi Yar, recalled: “I can’t forget the shouts of Shema Yisrael of the Jews. They also echo in my dreams.” In Ukraine, about 900,000 Jews were exterminated in dozens of murder sites. Large operations also took place in Berdichev and Uman during the Tishrei (Sept./Oct.) holidays.

On Yom Kippur of 5702 (1941), an aktion (roundup operation) was held in the Vilna Ghetto. In the town of Mir, Rabbi Avraham Hirsch Kamai, was murdered in a large aktion on Cheshvan 19, 5702 (Nov. 9, 1941). In front of the shooting pits, he said: “Accept all of this with love, like Rabbi Akiva, that exists in the last hour with all your soul , even if it takes your soul” (Ella Ezkera, vol. 6).

The sanctification of G-d’s Name by the People of Israel during the Holocaust is our point of connection to all of the People Israel and the martyrs. On this point of connection, the Rebbe of Slonim, known as the Netivot Shalom, stated: “And the issue of remembrance is not mere historical memory, but it is by which a Jew links himself to all of the People of Israel, which is an inseparable part of the People of Israel… The special meaning of remembering martyrs from generation to generation is that this is what connects us with the Source of holiness. Because the continuation of the generations of the People of Israel… like a chain in which each ring of coins is linked to its society, and this combination is the foundation of its existence”

Jewish memory is not content with merely embracing or mourning the past, nor with understanding and knowledge of it. Memory is meant to give meaning to the present and the future. It is an order, a deposit and a challenge, and it is not for nothing that the nickname “Am Zocher” (the Nation that Remembers) has stuck to us – because the essence of the values of the Jewish tradition is built on the design of memory.

This task was taken on by Ganzach Kiddush Hashem – to be one of the bearers of the torch of remembrance, to tell the younger generation and its children the song of faith that has not faded, to give them strength to continue and hold on to the chain. Part of the purpose of the discourse is to also remember what was in the past, the prospering Jewish communities. This is how we will ensure a Jewish future, more links in the chain. The strength of the entire chain depends on this link.

These days, when the nation passes before Him like “Bnei Maron” (sheep passing through a narrow passageway) – there is no doubt that the merit of the martyrs’ sacrifice 80 years ago stands for us.

In a letter to his son (on the week that the Torah portion, Noah, was read in 5706/1946) Rabbi Dessler described the destruction of Kelme, in Av 5701 (summer 1941), and compared the death of the martyrs to the joy of the Torah: “Indeed, how did the great ones of the world depart, as those who open hearts, from the dawn of truth? I remember the days of old, the night of the holiday of Simchat Torah in the Talmud Torah, that the rabbis of the house came out of the street gate, and went dancing through the city, dancing with all their might out of the enthusiasm of joy and singing with all their might, ‘Blessed are we, how good is our lot…’ Who can imagine what these supreme saints did at that hour? Strengthen their hearts, And they embraced their spirit, and were enthusiastic with immense joy at the mitzvah of sanctifying the Name of G-d, with weeping and wailing, they were dancing and singing… the same song of joy: ‘Blessed are we, how good is our lot…'”