The Torah was Exiled with Them: Torah in the Cyprus Detention Camps

More than the Voices of Great Waters: Rabbi Yitzchak Kalonymous Stein z”l

By: Devorah Surasky

The Yeshiva and Torah Study

As soon as we arrived there, some young people gathered and founded a yeshiva. The rabbi was a dear Jew from Budapest named Rabbi Yitzchak Stein z”l, and although we had no textbooks, only a few tractates of Bava Kama without interpretations, we would still get up in the winter early in the morning and study Bava Kama with Rashi (a rabbinic interpreter) and Tosfot (another rabbinic interpreter) according to our limited understanding due to lack of books. Later, Polish immigrants also arrived and the yeshiva expanded, and towards the summer we learned Tractate Makot with Ritva (rabbinic comentator)… and we were taught by the late Rabbi Meir Klibanski z”l, and later to distinguish between Chaim and Chaim, by Rabbi Chaim Yisrael Weinstein” (Rabbi Roter, The Gates of Aaron – The Hidden and the Revealed)

Rabbi Yitzchak K. Stein

Rabbi Roter shared with us his memories about these many waters, about the unquenchable love, about the zeal and the thirst of the deportees of Cyprus to study and teach Torah.

The spotlight is directed to the rabbi of the yeshiva, the lion of the pack, Rabbi Yitzchak Stein from Budapest, who dedicated himself to teaching Torah and initiated the establishment of the yeshiva. Who was Rabbi Yitzchak Stein? This riddle was solved on the study day held following the Cyprus project that Ganzach Kiddush Hashem opened in Bnei Brak on the 5th of Av 5782 (Aug. 2, 2022) in Bnei Brak. The writer and lecturer Mrs. Leah Fried shared with the audience the story of her father, Rabbi Yitzhak Stein z”l. In her description of his works and events, she placed emphasis on his stirring and important historical diary. He called the diary, in which he recorded his experiences, “Seven Years of Upheavals”. It was written in Hungarian, over a short period of time and at a frenzied pace, when the writer was in a kind of spree to document the events.

The family members bore witness to the diary in a family booklet they wrote to commemorate it:

The period of terror he personally experienced from 1941 to 1948 was recorded by their grandfather z”l in six thick notebooks… which he filled with dense lines in his eloquent handwriting while staying in a basement in the Mea Shearim neighborhood during the Israeli War of Independence. Straight from the ship he landed in the middle of the fierce battles and stayed in the same shelter together with the residents of the building… Outside, war shells whistled and he sat huddled in his corner, continuously writing down lines about his past and all that he left behind, and accurately recorded, as he did, all the things that happened to him” (Who Will Ascend the Mountain of G-d).

This diary, apart from being a family heirloom, is an important historical and Jewish source, as it contains accurate, authentic, and unique information: names and specific places, which also helped many in claims for reparations from Germany, and a host of rare documents. The diary is characterized by honest and direct writing that evokes empathy in the reader. Chapters of Jewish heroism and the Jewish stance are interwoven throughout the lines of the diary, described as a matter of course. The writer’s humility is a motif that cannot be ignored. In the sixth notebook, descriptions are devoted to the immigration to Israel and the period in Cyprus, descriptions that bring out the pulse of life of the writer and the illegal immigrants around him. From the testimonies of the illegal immigrants and those of other figures of greatness, a masterful picture of determination to continue the circles of Jewish life and hold the tree of life and the springs of the Torah becomes clear, a picture in which the call echoes: “All those who are thirsty, go to the water.”

“Seven Years of Upheavels” – The Notebooks of Granfather Yitzchak: The Untold Story

“As a matter of fact, I was already late in writing these memoirs. I cannot accurately describe the majority in a way that is faithful to reality, and also due to the great suffering – I have forgotten a great many events.” This is how Rabbi Stein opened his diary, and later moved on to descriptions of the events that befell him: “And so, I begin, July 16, 1940/Tammuz 15, 5700 is my wedding anniversary. If I still remember anything, it is of course related to things that happened to me, and that is what I will mainly describe, so it will be my diary.”

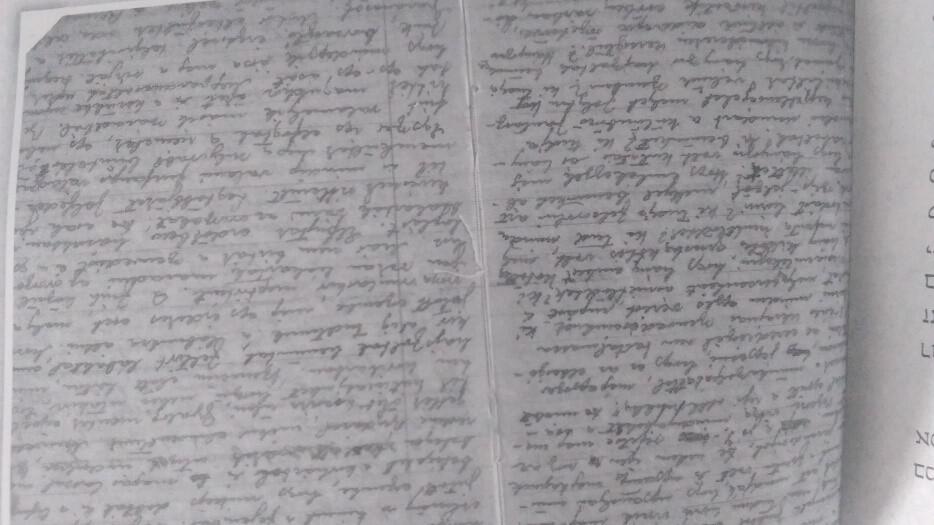

A picture of the authentic diary

Rabbi Yitzchak Stein was born in 5674 (1914) in Papa, Hungary, to a family of Torah scholars. The Stein family lived in Budapest with their toddler Rachel. The conscription into the Hungarian labor companies in 5702 (1942) (the Munka-Tabor) broke up the family. From this point on, Rabbi Stein began to walk on the path of suffering. Suffering, hardship, and horror were his lot in his upheavals across the Ukraine and Poland. The “slave army” became synonymous with the Jewish companies in the service of the Hungarian army, which faced humiliation, suffering, and persecution. A large part of the recruits were sent to the Eastern Front where the conditions of existence were extremely difficult: cold, hunger, and disease. Do not return the Jews – this was the instruction of the Hungarian army commanders. The land of Ukraine was soaked in their blood and many did not return. The fact that the writer of the diary is one of the conscripts that returned, strengthens its outstanding weight as a primary historical source of documentation. His experiences during the recruitment years were given a central place in the descriptions in the diary: the life of the conscripts as Jews alongside the suffering, horror, and persecution. “We unfortunately had to work at the wagon headquarters on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. We had to clean stables and brush horses. Unfortunately, we could only pray in the stable.” He concluded his descriptions of this time period as follows:

“But, before I separate from the discussion of forced labour, I want to point out that all the descriptions we have given here do not even reflect a thousandth of the three years of suffering in Ukraine. Who can describe every blow, kick, and slap that were repeated at every moment… How many times we were hungry and stood shivering from cold, broken from early in the morning until late at night in the rain, mud, snow, storms, etc.?”

At the end of the war he ended up in Germany and later in the Dachau camp. His descriptions refer to and detail his wandering journey, and go over the stops and the great suffering he experienced in each of them. After the liberation, he also came to Bergen-Belsen, where he testified to the Jewish revival: “Large shipments arrived from London; from America came Torah scrolls, all kinds of Torah literature, prayer shawls, tefillin (phylacteries) and kosher preserves. Here I received for the first time tefillin, a prayer shawl, and tzitzit (the fringes worn by Orthodox Jewish men).”

And as a man who sees his suffering, upon his return to Budapest he learned that his wife Esther had been killed in a bombing of the house where she was staying. In a miraculous way, he managed to find his five-year-old daughter, Rachel, and rescue her from a Christian family. In Budapest, he was active in Agudath Israel and the organization of illegal immigration and aliya (immigration to Israel): “I was offered a clerical position in the association and I accepted it. They assigned me the most difficult job, managing the ‘Bericha’ (escape) – that is, managing the department for illegal immigration in the Agudah.” The mission, in all its components, was challenging and dangerous and he fulfilled it with dedication and concern. Later he also came to Yugoslavia as an illegal immigrant.

Rabbi Yitzhak and his daughter were listed with 3,845 illegal immigrants on the Knesset Israel ship in November 1946. In his diary, he devoted space to the Knesset Israeli incident: “What happened – three English warships arrived and started forcing the people to pass, and the battle broke out. The people grabbed cans and started throwing them. One of the officers was hit in the head and he fell into the water. There was a volley of shots, two young men were killed and many were wounded. An unequal war began using tear gas and water hoses. One baby was suffocated, there were many old men, women, and children on the ship…And the transfer to the warships began. Thus came the end of our journey on the Knesset Israel ship. Everyone was searched; everything of value was taken. They gave food on the ship but most of the people started a hunger strike. For three days, we sailed along the shores of the country because, after all, discussions in our case continued, but since no results were achieved, we arrived on December 3rd in Cyprus.”

Arriving at this period of time, the diary writer described life in the detention camps. His descriptions reflect the complex reality of everyday life: “Everything the English gave was bad, the food was scarce and inferior. If not for the Joint and the canteen we organized, the food would not have been different from what it was like with the Germans. The clothes they gave were unusable, they gave us warm woolen clothing, while the sun was shining so much that we sweated even while naked. The military shoes were heavy and wobbly. There was no water, only two hours a day.” Rabbi Stein added and described the magnitude of the bond and mutual concern that prevailed among the detainees: “We carried oranges in sacks, bread, and potatoes to those who arrived after us.”

Close to Rosh Hashana 5708 (1947) he was permitted to immigrate to the Land of Israel, and on Yom Kippur and Sukkot he was already in the Atlit camp, which he also included in his descriptions: “On Rosh Hashanah I was again a prayer leader in Cyprus. The ship left on Saturday evening and on Saturday we did not get off the ship. On Sunday morning they took us to Atlit.”

Torah in Cyprus: No and no! It was a yeshiva in every way, and it was attended by mature boys and not children”

“Your father z”l was the first Rosh Yeshiva (head of the yeshiva) in Cyprus, and we were his students,” said Rabbi A.I. Roter to the family members of Rabbi Yitzchak Stein, the writer of the diary. He also described the Cyprus yeshiva in his memoirs. “At the time, grandfather told us that he gathered a number of children to teach them Torah, but Rabbi Roter protested against the condescending description and emphasized again and again: No and no! It was a yeshiva in every way, and mature boys and not children studied there” (Who Will Ascend the Mountain of G-d).

He humbly described his spiritual endeavor in his diary: “Later I taught for 5 months in the yeshiva. When the Agudath Israel’s group grew stronger due to the addition of more students, the yeshiva expanded and received a separate hall.”

Torah grew in Cyprus. Glorious figures and those who passed on Jewish tradition spread the Torah, established educational institutions, and Jacob’s voice was heard.

“In the Poalei Agudath Israel youth group, they learned Hebrew, and prepared for work in Israel, yet they were kept very much out of contact with the general youth village, and even obtained permission to live in a separate camp… When the group came to Cyprus, the members lived in unheated tents and read the Torah in dim lighting” (Dr. Menachem Oren, From the Other Side, You Will See the Land). This description refers to Rabbi Leibel Kutner’s group that arrived with the deportees of the ship “Arba Charuyut”. This group was established in Italy, in Santa Cesarea, where Rabbi Kutner operated educational frameworks for the youth in the group. He took his works to Cyprus and with the arrival of the group, the Torah classes and the educational institutions for the boys were renewed.

“Even at their third stop, the Cyprus stop, all the members of the group, the older and the younger, were gathered in living quarters next to each other… Tents were immediately assigned for the institutions… and tents for the classrooms” (Rabbi Baruch Lev, Let These Bones Come Alive)

“Without reference books, there is no Shulchan Aruch (Jewish law book), without talking about books of responsa” – this is how the She’arim newspaper describes the activities of Rabbi Bentzion Rotner, a rabbi in the camps in Cyprus. Upon his arrival, he immediately began giving Torah lessons to anyone who needed them without conditions, out of concern for Jewish education and building families. About his activities and educational and Torah enterprises Rabbi Stein, the diary writer, wrote: “Beautiful synagogues, administrations were founded, a yeshiva and Talmud Torah school were established. The youth village was in a separate camp. The Agudath Israel also had a youth village, where they learned Gemara, Tanach (Torah, Prophets, and Writings), geography, writing… Later, more and more people arrived, including Rabbi Bentzion who was elected the chief rabbi, the yeshiva and the Torah Talmud expanded.”

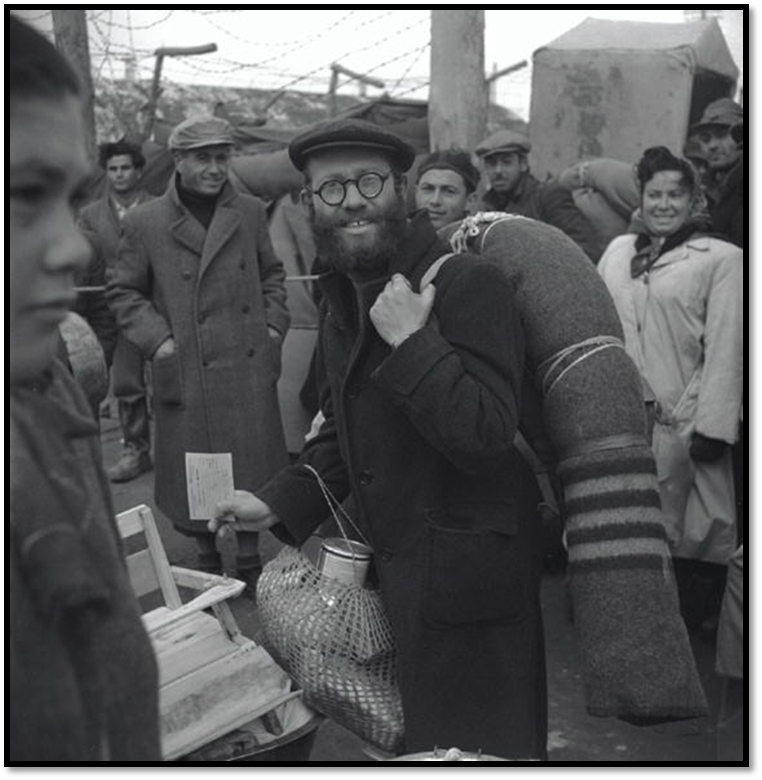

A Torah lesson in a Cyprus detention camp

On the study day, his daughter, Mrs. Riva Abramowitz, who accompanied him as a girl and shared with us her experiences among the exilees of Cyprus, shared with us information about the blessed works of Rabbi Yehoshua Menachem Ehrenberg, the author of “Davar Yehoshua”, who served as chief rabbi of the detention camps in Cyprus.

Rabbi Ehrenberg was sent from Israel to Cyprus. Many Jewish homes were established to his merit, and he was known for his dedication to the issue of releasing agunot (women who did not know the fate of their husbands) and he even founded a yeshiva. This yeshiva left its mark on its students, as evidenced by Z. Berkowitz, the daughter of Rabbi Israel Greenbaum, who was one of its students.

“In Cyprus, Rabbi Ehrenbager z”l founded the yeshiva which numbered about eighty young men, with my father z”l sitting amongst them and he was prominently active in all spiritual matters of the yeshiva. The yeshiva in Cyprus operated in a unique format. Rabbi Ehrenberg, who was specially sent from the Land of Israel to take care of the spiritual activity in the camp, rewarded the young men at his yeshiva, with each young man receiving ‘twenty grosh'” (Z. Berkowitz, The Way of Israel).