“That Horrific Morning” – Cheshvan 7, 5702 (Oct. 28, 1941), 80 Years Since the “Great Aktion” in Kovno

“The Black Day,” “The Day of Horrors,” “The Day of the Great Aktion” – Cheshvan 7, 5702 – October 28, 1941, this is how the bitter day has become known. What happened there? And what is the halachic question that troubled Rabbi Eliyahu, the refugee from Warsaw, during the aktion? Were there rumours about the extermination of Lithuanian Jewry? What is the new information gleaned from a document in the Prager Collection of Ganzach Kiddush Hashem? These are the episodes of greatness and glory that were recorded in the Kovno Ghetto.

Researched and written by Mrs. Devorah Surasky, Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

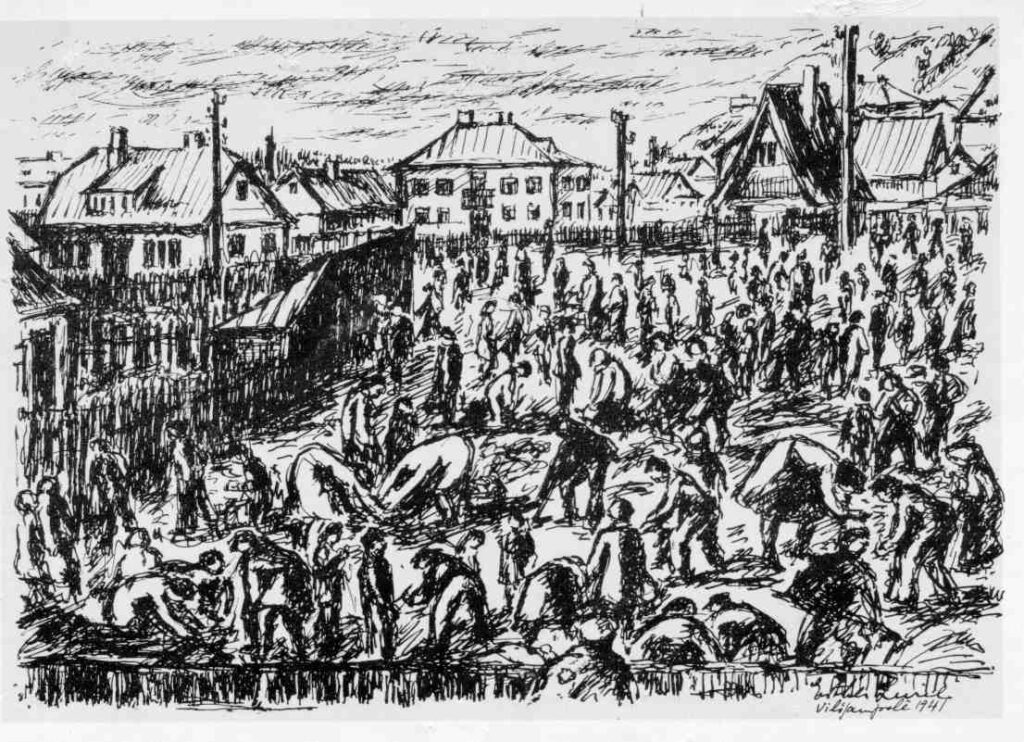

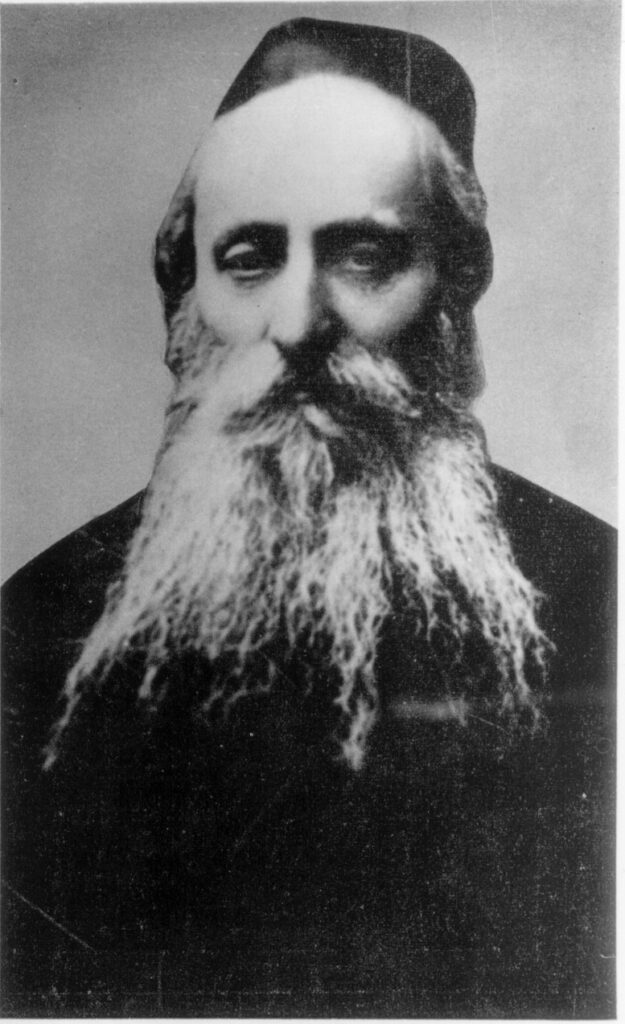

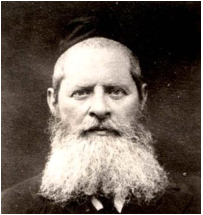

About 26,000 Kovno Jews crowded together in “Democrats Square” in the ghetto one morning at six o’clock. The Ältestenrat (Council of Elders) received an order from the Gestapo to announce a general obligation to report to the square. Incompliance woud be punishable by death. The Ältestenrat was faced with a complex dilemma in the face of the German demand: should it pass on the instruction and fulfill the order or resist the demand? The Kovno Ältestenrat, headed by Dr. Elchanan Elkes, was known for its high moral standards and cooperation with the Jews of the ghetto, and more than once the Ältestenrat consulted with Rabbi Avraham Duber Kahana Shapiro, rabbi of Kovno, as they did in this difficult event.

Rabbi Ephraim Oshry reported on this: “The Ältestenrat immediately sent a delegation of 4 people to the head of the religious court of Kovno and their souls were in question – should they obey the German order and hand up the aforementioned ad or not, because according to the information they have, a significant portion of the people gathered in this lot will be executed… Upon hearing this new decree, the rabbi began to tremble all over with grief, until he almost fainted… That night he did not return to his sleep, but looked for books that would help him make a decision on Jewish law, and after a long deliberation he informed them of the verdict in this manner: If a decree has been issued on a part of the People of Israel, and there is a possibility by various means to save some of them… the heads of the community must have strength in their souls and act out of the responsibility given to them. They should take all measures to save everyone who can be saved” (She’elot U’Teshuvot Mimaamakim – Responsa from the Holocaust, Part 5, Question 1)

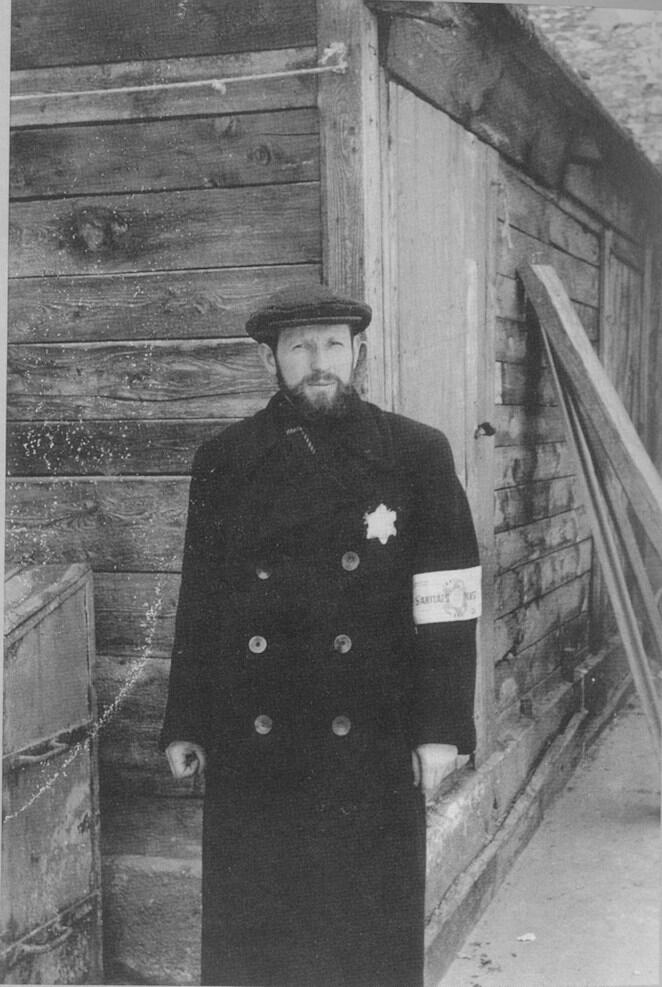

Rabbi Avraham Duber Kahana Shapiro, the rabbi of Kovno

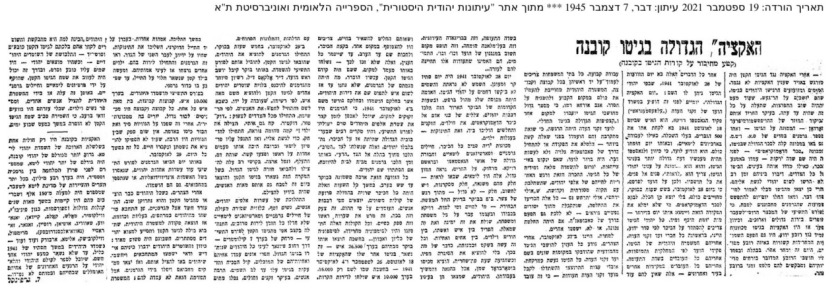

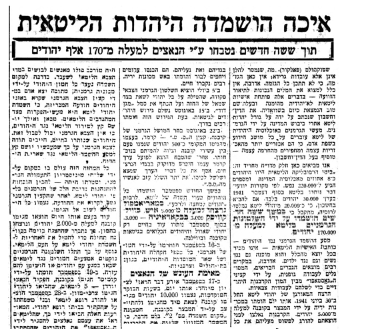

Newspaper clipping, dated December 7, 1945, about the Kovno Ghetto

And so the prisoners lined up in order, grouped by family, surrounded from all directions by machine guns, Germans, armed Lithuanians, and curious spectators who gathered around to witness the spectacle…. Thus began the work of the selection that continued until the evening hours: “The sun was not visible and the sky did not ask for mercy on the Jews of the ghetto, and in the early hours of that damned morning thousands of Jews walked, shadows of human beings… at eight in the morning the act of choosing who would live or die began.” These hard facts were described by L. Garfinkel, who was the deputy chairman of the Ältestenrat, in the Devar newspaper, December 1945. “The Great Aktion in the Kovno Ghetto,” was the title of the article and in brackets it was indicated that the article was an “excerpt from an essay on the events in the Kovno Ghetto.” Immediately after the war ended, Garfinkel began the work of documentation, and his compositions are among the most prominent of the ghetto chronicles.

Over nine thousand people were transferred to the small ghetto that served as a transit station. The next day, under heavy guard, they were taken to the Ninth Fort, where they were shot in huge pits. The Ninth Fort is one of the chain of fortresses that surrounded Kovno and were built back in the time of the czars. It is located near the city and was used as one of the mass murder facilities (like the Fourth and Seventh Forts). In this killing place, over fifteen thousand Jews of Kovno were murdered, as well as several thousand other Jews who had been deported to Kovno from Germany and Austria.

The Ninth Fort

- A question from Hell at the time of the aktion: “What is the version of the blessing over Kiddush Hashem (sanctification of G-d’s Name)?”

- Then, in this situation, Rabbi Eliyahu of Warsaw, may G-d avenge his blood, one of the refugees who escaped from Warsaw, approached me. He asked me what is the wording of the blessing for sancitfying the Name of G-d?” (She’elot U’Teshuvot Mimaamakim – Responsa from the Holocaust, Part 2, Topic 3). The questioner, as Rabbi Oshry testified, wanted to know the answer not only for himself, but to pass it among the people and teach them the law. “Who sancitified us in His commandmant to sanctify his name in public” was the answer provided, based on the opinion of the Shlah rabbi (Rabbi Yeshayahu Horowitz). Rabbi Ephraim Oshry, who was close to Rabbi Shapira, compiled the set of questions addressed to the rabbi in the ghetto in his well-known collection She’elot U’Teshuvot Mimaamakim – Responsa from the Holocaust (in some of the questions he himself made the rulings due to the rabbi’s illness, as well as following his death). From a perusal of the Responsa, it is clear that a number of halachic questions revolved around the Great Aktion, which testifies to the greatness of the questioners. Undoubtedly, the Great Aktion left its mark as a tragic and formative event – as the collection of documentation sources shows – and as a significant part of the memory of the Kovno Ghetto. The work and its contents are a living memory burned in to the testimonies, diaries and memories of the ghetto survivors.

In the testimony of Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan Gibraltar, who at the time was aged 12 years and three months, he tells of his request to his father on the eve of the Great Aktion. “Tonight is the last night of our lives. I want to have the merit of putting on tefillin!” His father agreed and replied “tomorrow morning, you will put on tefillin”…in the morning, while it was still dark, my father looked and said: “now you can put on tefillin.” I put on tefillin for the first time! (Survivor Testimony Database, Ganzach Kiddush Hashem)

One of the last survivors from Kovno, who passed away, was Rebbetzin Esther Rivka Zacks, the daughter of Rabbi Mordechai Shulman, the head of the Slobodka Yeshiva, who was the son-in-law of Rabbi Yitzchak Isaac Sher (Rabbi Mordechai married his daughter, Rebbetzin Chaya Miriam), who was also a head of the Slobodka Yeshiva. In her memories as a child, she described the horror and the impression it left on her: Rauca (Nazi officer) did not take any consideration of family groups. With a devilish smile, he separated families at will and sent them to opposite sides. Those who were sent to the good side were placed at the end of the square, and those whose fate was determined were immediately transferred, under heavy guard, to the small ghetto… They could not choose at all, and and this point he tapped me on the shoulder. I quickly looked around and that’s how I escaped. God wanted me to live, it wasn’t me who understood where to push… After the mass murder, the singing and cheerfulness of the Lithuanian murderers, who returned drunk and merry from the terrible massacre they had committed, echoed with clarity.”

Rabbi Ephraim Oshry following liberation

- And it was after the aktion…

The Great Aktion closes the first tragic period in the ghetto’s three years. The Jews of Kovno began to drink the German occupation’s cup of poison at the end of June 1941. Pogroms and mass murder began. With the imprisonment of the Jews in the ghetto at the end of August 1941, in Slobodka, a suburb of Kovno , the systematic killing increased. This period of time in the ghetto chronicle is known as the “period of mass murders”. The mass murder was carried out by the Einsatzgruppen and Lithuanian partisans, and the Great Aktion constituted the peak of the abuse.

Death knocked at the windows of the Jews of Kovno and there were hardly any homes without someone who had been killed. Families were broken up; children returned home without parents. About 17,000 Jews remained in the ghetto. The period of about two years – from the Great Aktion to the fall of 1943 – was nicknamed “the quiet period in the Kovno Ghetto“, for its relative quiet. This is not the calm after the storm, but rather a storm itself that was quiet.

The ghetto inmates had to face the harsh reality of life in the ghetto: they had to work in demanding forced labor positions as part of the war effort. The meager food supplied to the ghetto was not enough and hunger was a constant. Various decrees were imposed, including the decree to hand over books, the closing of synagogues, and a ban on praying in public. From the fall of 1943, thousands were sent to labor camps in Estonia and to camps near the city of Kovno. The ghetto became a concentration camp. In July 1944, with the approach of the Red Army, the Germans accelerated the liquidation of the ghetto. At the time of its liquidation and the liquidation of the camps adjacent to it, about seven to eight thousand people were transferred to camps in Germany: Dachau, Stutthof and others. About a month later, the city was liberated by the Red Army.

The Jews of Kovno moving to the ghetto

Germany’s defeats in battle, especially on the Eastern Front in Russia, led the Germans in 1943 to start hiding the evidence of their perpetrations. In this framework, “Operation 1005,” the code name of the operation to hide their evidence, began at the Ninth Fort. Jewish prisoners were included in these operations, who in a daring operation managed to escape, and to a certain extent brought out the story of the fort.

The tactics obscuring the evidence were an integral part of the complex issue of information.

- The knowledge and search for sources of information: How Lithuanian Jewry was destroyed and the rescue attempts.

“How Lithuanian Jewry was Destroyed,” “Over 170,000 Jews were Slaughtered by the Nazis in 6 Months,” – These were the compellnig and eye-catching headlines in the Haaretz newspaper in August 1943

In these reports, given by a non-Jewish Lithuanian person residing in Sweden, there is a detailed and hair-raising account of the mass extermination of Lithuanian Jewry. “The October Horrors” – that’s what the days of terror in Kovno were called. “On October 27, the Nazis rounded up over 25,000 Jews in the ghetto square. The Jews were ordered to pass in front of the Nazi officers… The two executioners cut off the fate of passers-by.” This is some of the chilling data in the article. The question is what the meaning of these pieces of information was in those days and whether and how they were received.

What happened to the remaining Jews in the Kovno ghetto? Who was left of the “cedars of Lebanon” and Torah teachers? Who survived the continuation of the horrors and destruction of the ghetto? These were the questions that troubled the Jewish world, searching for bits of information. Information in the press of the time shows that even during the war, information arrived, but the picture was very blurry. In the Haaretz newspaper in September 1944, there is a news item entitled “How the Rabbis of Lithuania were Murdered“, which reports on news that came in a letter from Rabbi Ephraim Oshry, who detailed the fate of the rabbis of Kovno and the murder of Rabbi Elchanan Wasserman and other rabbis in the summer of 1941.

Haaretz newspaper, Sept. 12, 1944

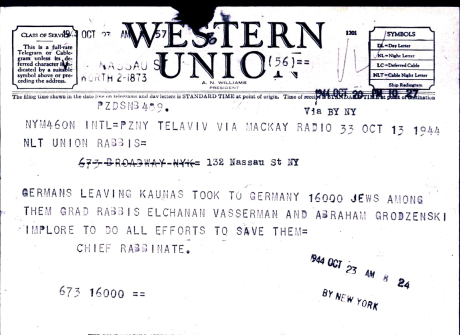

A unique document from the archives of Ganzach Kiddush Hashem found in the “Prager Collection” (the treasure trove consists of testimonies and unique documents that were collected and compiled by the writer and researcher, Rabbi Moshe Prager, the founder of Ganzach Kiddush Hashem, whose life mission was to pass on the memory of the Holocaust) explains a layer of information related to the issue of knowledge about and the rescue attempts of Kovno Ghetto rabbis. This document is a telegram from October 1944, sent from the rabbis of Tel Aviv to the Vaad HaHatzala (Rescue Committee) in the USA: “The Germans are leaving Kovno. They took 16,000 Jews to Germany, among them rabbis: Rabbi Elchanan Wasserman and Rabbi Avraham Grodzinski. We aimplore you to do all efforts to save them.”

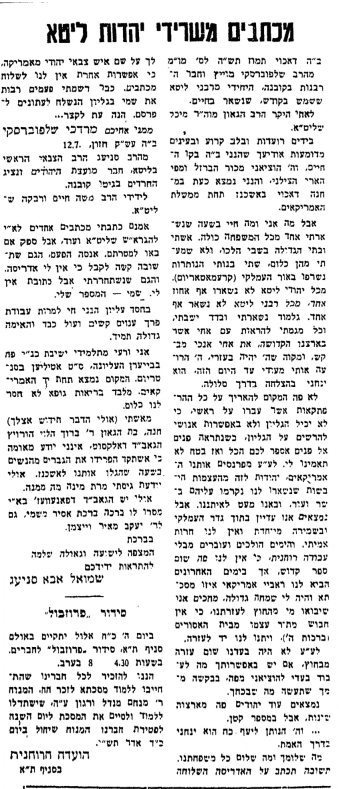

The telegram indicates that at this point in time they still did not know what had become of the rabbis of Kovno, and even tried to begin rescue efforts with the knowledge that the ghetto evacuees were being marched to Germany. “Letters from the Remnants of Lithuanian Jewry” published in the newspaper Shaarim in September 1945 reported important information: “With trembling hands, a broken heart, and tearful eyes, I inform you that I am in God’s line of life, and God took me out of the horrible place and from the mouth of the lion He saved me, and I am now in the Dachau camp in Ashkenaz” – This is what Rabbi Mordechai Shalpobersky, who was a member of the Kovno rabbinate, told his brother. Another sign of life is the letter of Rabbi Shmuel Abba Sneigas, also one of the remaining Kovno rabbis of that time.

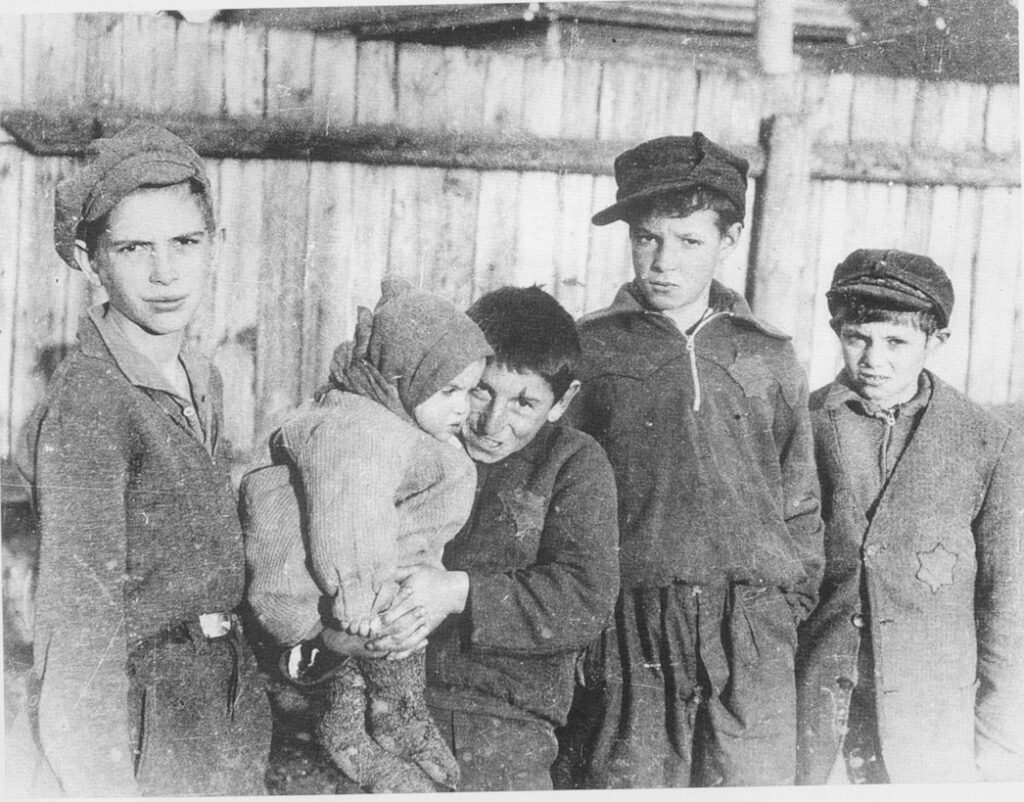

Tzvi Kadoshin and His Photos – The Kovno Ghetto through the Lens of the Camera

Close to a thousand photos can be found in Kadoshin’s collection which constitutes a central pillar in the treasures of visual documentation of the Kovno Ghetto. The photos are the fruit of labour of the photographer, Tzvi Kadoshin, who immortalized life in the ghetto using an underground camera, since photography was forbidden there. The fact that he was employed in the hospital’s x-ray department enabled him to obtain film and a lab to in which to develop the photos. The images were then smuggled into the ghetto using crutches. The photos are characterized by sensitivity and empathy. Some of them were taken though the buttonhole of his coat with a specially created camera.

- Chapters of Greatness in the Days when Kovno Jewry were at rock-bottom

Even in the days of darkness and humiliation experienced by the Jews of the Kovno Ghetto, the image of their greatnes arose and shone. Further evidence of this was recorded in the Prager Archive. The original documentation (in Yiddish) was of course written by hand.

Rebbetzin Chaya Miriam Shulman, who supported many people in the ghetto and especially children, said that during the days of famine that took over the ghetto, Rabbi Shapiro gave a halachic permit to the forced labourers who walked a long way every day to drink the water of the non-kosher soup, on the condition that they be careful not to eat the pieces of non-kosher meat in it. However, many of the Jews of Kovno did not even use this permission and chose not to drink it.

Rebbetzin Shulman’s Testimony

It is now three years since the passing of Rebbetzin Rivka Wolbe (Cheshvan 16, 5779 – Oct. 25, 2018), daughter of the spiritual overseer of the Knesset Yisrael Yeshiva in Slobodka, Rabbi Avraham Grodzinski, who perished in the last days of the ghetto in the hospital that was set on fire by the Germans. In her testimony, which was given to Ganzach Kiddush Hashem and included in her book “Your Faith in the Night”, she describes Slobodka: “Every Shabbat night, the students who were still left in the yeshiva used to gather in our house. My father would whisper in their ears words of Torah and words of strength and encouragement. These boys were broken and torn in body and soul They remained isolated, the only ones from their entire family, and the harsh labour they performed in the German factories completely exhausted them. The words of the Torah and the encouragement that Father showered on them were a source of strength and motivation for them to continue and not break. In his words you could sense the deep and consistent preparation for the sanctification of G-d’s name.”

Rabbi Avraham Grodzinski, spritual overseer of the Slobodka Yeshiva, Kovno

“He even suggested to them that they all sign to keep certain observances as a merit to stay alive…and these are the things: 1) Faith 2) Shabbat observance 3) Family purity 4) Caution from eating non-kosher foods 5) Charging interest 6) Wasting time that could be used for Torah study 7) Love of the People of Israel 8) Kindness 9) Contentment 10) Trust in G-d 11) Education of children 12) The Land of Israel.”

Slobodka was the symbol of Kovno as a beacon of Torah and morality. From there came leaders, and from her trees many fruits and plantings grew. The destruction of the Slobodka Yeshiva in its glory days was part of the terrible destruction of Kovno Jewry. The yeshiva was a symbol of Jewish life, its death and destruction belonged to all of Kovno. This is indeed what the poet Avraham Axelrod, a refugee who ended up in Kovno (he perished in the liquidation of the ghetto), sought to convey in his song “In the Slobodka Yeshiva“. The song was written within the walls of the ghetto following the terrible aktions, at the end of 1941. Through its word, it described the will of the last beadle of the yeshiva, asking to remember the atrocities:

“When you merit liberation, Jews

tell your children the tales

of our blood that flowed there

of the gruesome murders

and graves, that death that was seen there

at the Ninth Fort”

The song used a well-known tune

The will of the beadle was indeed fulfilled, as the words of the song state:

“…The beadle will leave, his will will remain

and in letters of gold it will be recorded and described,

the life that was in the ghetto, his wish, his poem.”

Toddlers in the Kovno Ghetto

But not only ghetto life has been described: Slobodka and Kovno were not just a memory from the ghetto, the aktions, and the death forts.

Slobodka, “the mother of the Yeshivas,” is a living and existing fortress of Torah and morality, its fortress is spread all over the world, and magnificent yeshivahs were built from its model, and from them we live and exist.

Children in the Kovno Ghetto