Rabbi Moshe Prager Z”L

Founder of Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

40 Years Since His Passing (5744-5784/1984-2024)

By: Rabbi Aharon Surasky

A rare figure who represented “seeking the good of his people” (Esther 10:3)

Rabbi Moshe Prager z”l was a prototype of a Jewish-Israeli. His publications, as a great and inspiring writer, one of the greatest creators and generators of charedi (ultra-Orthodox) literature and journalism for generations, largely overshadowed other aspects of his personality, which in fact supported his creative spirit in writing as well. He was surrounded in his life by many friends and admirers whose emotional connection to him was not established just from reading his essays and compositions, but rather through personal contact against the background of his lively activities for every Jewish cause, or even more so due to his abundant friendship and love for every Jew wherever he is, with his chassidic soul and spirit.

The eulogy written in the Hamodia newspaper, upon his death, that “we will long miss the blessed days when Rabbi Prager was enshrined among us,” did not miss a hair’s breadth. The longing, as we move away from those days, increases and increases, pinching the heart without respite. In his midst, miraculous waves of Jewish vitality and eternal optimism rippled, which swept people close to him with dynamic power. His personality sprinkled around its sparks and flashes of joy and love, trust (in G-d) and hope, which ignited into a tremendous warming flame. These qualities were not in him temporarily, but were deeply rooted in his faith and chassidic worldview. This, without a doubt, is the meaning of the wonderful vision that was embodied in him, a survivor of the Valley of Killing, which came out of the whirlwind of blood forged and full of life, with his whole being exclaiming his mighty desire and confidence in seeing the prosperity and goodness of the Jewish People. This is where his personal charm sprouted, which captivated people near and far, religious men, and chassidic people, educators and statesmen, who boasted of the intimate friendship they had with him, and indeed, remained to a large extent enthralled after he passed from our lives. It would not be surprising then that his memory is cherished with intense longing.

With all that said, the image of his original personhood is etched in our memory first and foremost as a great and versatile writer. The longing for him is particularly evident among the old guard of pen-wielders in our practice, who bear the brunt of the ongoing creation of charedi literature and journalism, through which we try to clarify and interpret everything that is happening in Jewish life and in the entire world through a pure theological perspective. Who like him was able to realize and properly fulfill this heavy task with his blessed talents, his thoughtful fruits of labour, and the fervor of faith that turned his writing into “black fire on top of white fire.” Fire illuminates darkness in the soul and warms the heart.

A flagbearer of charedi journalism and literature

Rabbi Moshe Prager z”l belonged to the first generation who arose in Warsaw at that time – between the two world wars – to “wrest the spear from the hand of the Egyptian” (Samuel II 23:21) with a force of spirit, and create charedi literature and journalism, as a counterweight to the flood of gossip by the “maskilim” (englightened) and the secular.

He may have been the youngest of the group of charedi writers who held the banner of war, and polemized with them over the pages of the Agudah newsletter “Das Yiddishe Tagblatt,” but even then, while he was young, he excelled with his witty and sharp pen that betrayed his inner self, as in the wise saying that “the pen is the language of the heart.”

The notes of Moshe Mark (his original family name from his father’s home) were eagerly read by multitudes of religious readers, and became well-known.

His spiritual connection to Ger chassidism

Rabbi Prager was born in 5669 (1909), the year in which the preparatory conference for the establishment of Agudath Israel was held in the city of Homburg, and indeed he once wrote about himself “I am child of Agudath Israel.” He renamed himself “Prager” during the Holocaust, to remind himself of his beloved hometown that faded in the smoke, the Warsaw suburb “Praga” on the other side of the Vistula River, where he was born and grew up (this is also where his close acquaintance grew with the genius Rabbi Menachem Ziemba, may G-d avenge his blood, who was a resident of Praga, and whom he greatly admired). The home of his father, Rabbi Shmuel Yechezkel, may G-d avenge his blood, was full of Ger chassidism. On his mother’s side, Rabbi Moshe was one of the descendants of a line of rebbes, beginning with the Chiddushei Harim. His grandfather, his mother’s father, Rabbi Menachem Mendel HaKohen z”l, was the son of the older sister of the Rebbe of Piltz, Rabbi Pinchas Menachem z”l (known as the Shiftei Tzaddik), son of the daughter of the Chiddushei Harim.

When he was six or seven years old, his father took him to Gur (Gora Kalwaria, Poland – the place of origin of Ger chassidism), for the holiday of Shavuot, and from then he was tied to the soul of the Rebbe for his whole life. “What am I in Gur? I drop from the sea,” he later wrote of his emotions as a young child, “however, I am aware that everyone will be examined in one review,’ the Rebbe counts and counts every drop in this sea, and clearly distinguishes between each drop.” The good eye of the Rebbe, the Imrei Emet z”l, with his warmth and watchfulness was on Rabbi Prager even in the days when he joined the charedi writers’ group.

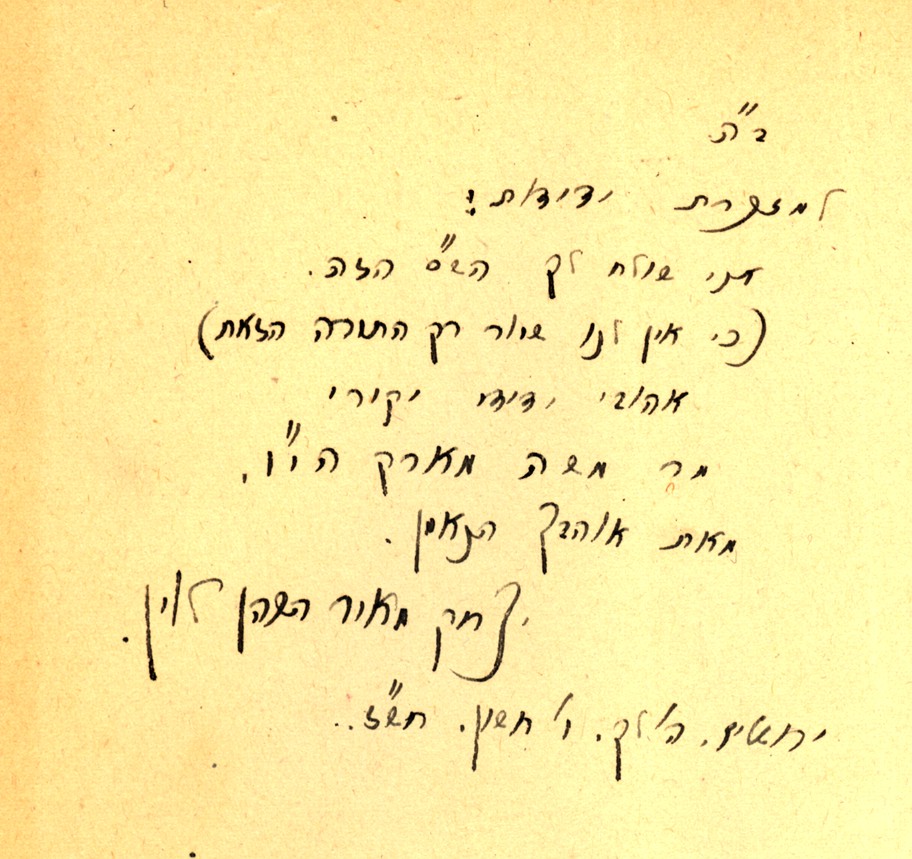

Until the end of his life, he emotionallly told the story of the shocking encounter with the tzaddik (righteous man) he had in the courtyard of the palace of the Prime Minister of Poland, Prof. Bartel, when the Gerrer Rebbe z”l with the Chafetz Chaim z”l and the Belzer Belz z”l came to convey the evil of the decree about Torah education, in the year 5690 (1930). For him, the opportunity to join one of the Rebbe’s trips to Israel was an exciting experience, and he published his impressions in a special book, “Oif der Vegen von Eretz Yisrael,” (On the Roads of Israel) which was published by “Menora” (Warsaw, 5694/1934). During that visit, he purchased a plot of land in Bnei Brak and saw himself from then on as someone tied by the umbilical cord to the Land of Israel. He was also close to all the members of the Rebbe’s family, especially to his son-in-law Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Levin z”l, and his brother Rabbi Pinieh z”l, the sons of the Rabbi of Bendin z”l. A special closeness bound him to the genius Rabbi Meir Shapira z”l of Lublin, who expressed a wonderful friendship when he wrote to Rabbi Moshe in a letter: “to the one who sits in the chambers of my heart,” and when he entrusted him to represent the interests of his great yeshiva at a press conference held in Lublin.

From Heaven it was decreed that he would be able to take part in the rescue of the Gerrer Rebbe from the Valley of Tears, and thus his life was also saved, which according to Rabbi Prager’s perception it was the test of “the ark carried its bearers” (Talmud Sotah 35a). It is amongst G-d’s secrets why he was sentenced to become bereft of his entire family, who were killed for the sanctification of the Name of G-d in the Holocaust. Rabbi Moshe remained alone. However, he saw the miracle of his survival as having a purpose, as a double mission assigned to him by G-d: on the one hand, to mourn the Holocaust victims and tell over its horrors, and on the other hand to serve as the bearer of the belief and torch of faith that G-d will not forsake His people and that the Jewish People are eternal, these because of the power of the heroism of those who sanctified the Name of G-d and maintained their G-dly image, and in light of the revival that began to emerge before his eyes. It was then that his great writings began in full swing, and he produced dozens of compositions and hundreds of articles and essays on the topics of the Holocaust, and instilled in the consciousness of two and three generations an original perception of the destruction and the revival that followed – in the spirit of Jewish continuity. Like Rabbi Yehuda HaLevi wrote in his time, calling to Zion, Rabbi Prager called to the Jews of Poland: “Crying for your suffering, I am a jackal.”

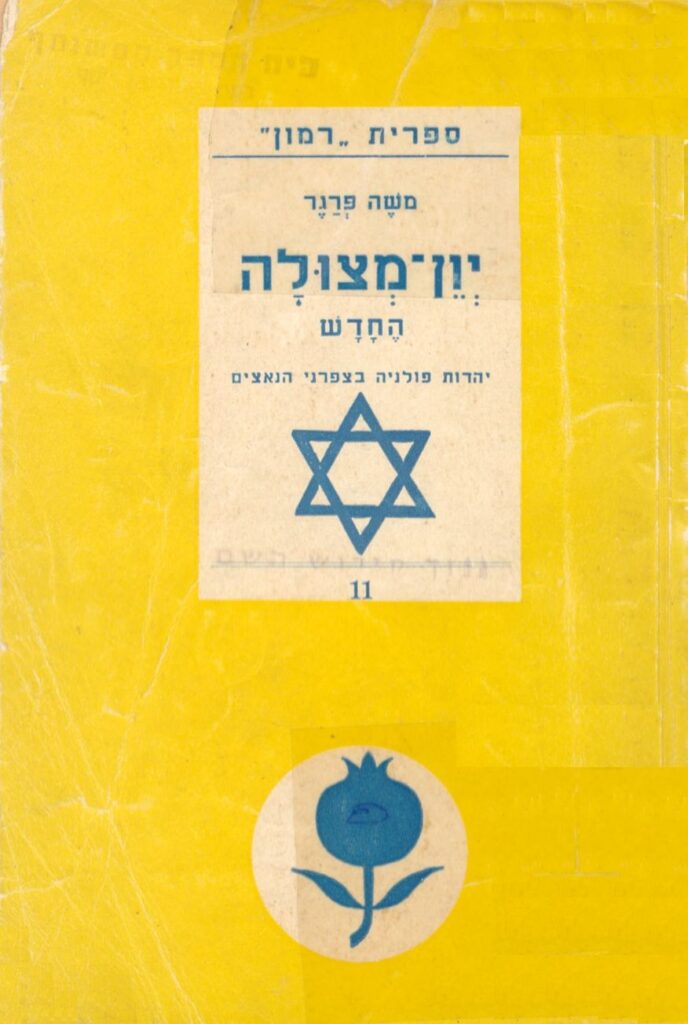

His life’s work – Holocaust research and commemoration

Indeed, his activity on this level began while he was “there,” immediately after the Nazi invasion of Poland, when he initiated and established a secret office near the Joint office in Warsaw with the aim of collecting and compiling first-hand information about the brutal campaign of atrocities by the Germans against the Jews of Poland, and their escape abroad, in order to call on the conscience of the world. Even when he left Poland with the entourage of the Gerrer Rebbe, Rabbi Moshe brought with him important original documentary material, parts of which later saw the light of day in his works. From the moment he set foot in the Land of Israel, he devoted himself to the holy mission, and persevered tirelessly in it for the next 45 years, until he was rightly considered to have paved the way for the study of the Holocaust period. His first composition was “Yeven Metzula HaChadash – Yahadut Polin B’Tzafranei HaNazim” (The Abyss of Despair – Polish Jewry in the Nazi Clutches), published in 5701 (1941). After that, his book, “Churban Yisrael B’Europa” (The Destruction of the Jews in Europe) was published, in which he discussed the motives of Hitlerism, which fought bitterly with the spirit of Judaism and called for its extermination. At the same time, he published dozens of alarming articles with previously unknown revelations about the incredible scope of the destruction machine.

With the defeat of the Nazis, he went to visit the displaced persons camps in Europe. Thus he gathered from the ash heaps of the furnaces sparks of sanctification of the Name of G-d, and from the abysses of sorrow and bereavement he met the sounds of faith of the survivors that he stored with a trembling hand in the collection of Holocaust poems “Min HaMeitzar Karati” (From the Depths I Called Out). In his book “Nitzotzei Gevura” (Sparks of Glory), which made a special impression, he revealed manifestations of spiritual heroism and moral courage of the victims of Nazism during the years of terror. In his preface to this book, he noted that this is not about “literary imagination” but about “terrible-magnificent reality,” and added: “If the things in the book are wonderous – they are the epitome of a generation of wonders; if they shatter the soul – then they reflect a terrible, sublime, emotional period.” It can rightly be said that in these stories the satanic horror of the oppressors and the heroism of the Jewish soul are joined as one tissue, and therefore they conquer every heart thanks to the inner truth that pulsates within them.

Rabbi Moshe Prager wrote a special large-scale work about Jewish heroism in the Holocaust called “Ach V’Achot” (Brother and Sister), with the subtitle: “Sipur Gevura MiSaarat HaTkufa” (A Story of Heroism from the Storms of the Era). He began to publish this large and extensive feature story on the pages of the weekly “Hamodia HaTzair,” since its founding in 5712 (1952), and in the sequels. After that – decades later – he processed and added to what was published in “Hamodia HaTzair” and submitted this important work for publication by “Mesha’evim,” and in the end the work grew and expanded into four volumes. Rabbi Prager considered the series of books “Ach V’Achot” to be one of the best of his diverse works, and defined the preparation for writing them as his life’s task. This is what he himself wrote in the introduction to “Ach V’Achot”: “The author put in great effort, wandered constantly across countries, lived for a long time in the displaced persons camps, and inclined his ear and heart to everything that was spoken by the survivors. This is how he collected detail by detail, line by line, their acts of heroism, and the strength of their stance to sanctify the name of Heaven – and he actually saw this as his life’s mission.”

Lamenting the Destruction and Telling about the Miracle of Revival and the Saving of the Torah

Even though Rabbi Moshe Prager did not physically experience the Valley of Tears, his soul remained stuck “there,” entirely scorched and bruised, together with his Jewish brethren who went through all the “seven sections of hell” in the ghettos and the forced labour and death camps. The survivors who read “Nitzotzei Gevurah” (Sparks of Glory) after the war, in which he describes in a life-like way, the existence behind the barbed wire fences in the camps and on the brink of the gas chambers and death furnaces, found it hard to believe that the author was never there. Only those whose souls remained in the Valley of Tears to the end could write as Rabbi Moshe Prager wrote. Later he wrote his popular books “Elah Shelo Nichne’u” (Those Who Never Yielded) and “Galed L’Yahadut Europa” (Memorial for European Jewry), in which he highlighted again the two central motifs in his study of the Holocaust: the main goal of Nazism – a war against the spirit of Judaism, the Torah and its morality, to the point of their extinction; and the Jewish spiritual heroism revealed in the coping with the (Nazi) Satan.

“The Nazis’ war was not aimed at the Jews, but at the spirit of Judaism,” he used to say. “The living Jews, the bodies of the Jews, were the target of the shooting only because the cursed murderers were sure that the Jews carried the Jewish germ (“Bacillus Judaicus”) and that the spirit of Judaism is truly in the blood of the Jews, which the Satan fears” – Rabbi Prager spread this idea tirelessly.

As a profound thinker, Rabbi Moshe Prager stood against on the roots of the racist philosophy that was laid at the foundation of the Hitlerite movement, and on the animalistic motives of the millions of executioners who worked in the service of that evil idea. One will not find in all his works even one sign of despair or depression, though. He never sought to instill sadness or grief in his readers. Because on the contrary, the purpose of his writing was to reveal and find rays of light even at the height of concealment in the days of killing and extermination, to discover sparks of light of true Jewish heroism and resistance, typical Jewish perserverance, and above all, the strength of Jewish eternity. Even in his shocking lament over the destruction of European Jewry, the “Megillat HaShoah” (Holocaust Scroll) that was added to the Mishnas studied in memory of the Holocaust victims, he concluded his painful lines with “thank G-d that we did not die” and pointed to the wonder, the fact that “even in this generation of the Holocaust, both disasters and miracles were involved.”

In his wealth of spirit, he was always able to link the destruction and extermination with the renewed revival and flourishing of Jewish life after the Holocaust. Only the scroll was burned but the letters flourish. His book “Galed L’Yahadut Europa,” in which he created a memorial for dozens of holy communities that were destroyed, he signed off with a description of the existence of the central fortresses of the spirit in the halls of Torah and chassidim, under the title “The miracle of saving the Torah in our time.” In their revival, Rabbi Moshe Prager saw the seeds of prosperity and the growth of Torah Judaism, seeds that germinated over the years, as our eyes see now. He was endowed with the ability to see into the future, with an eagle’s gaze, in days when no one dreamed of it, and he already knew that a movement of returnees to Torah Judaism was coming closer. He knew that from the ashes of the furnaces a new generation of those who promise eternal Jewish existence would emerge, and such a vision cannot occur unless “all roads lead to faith.”

He published his thoughts on this subject, as well as on many other topics related to the Jewish existence in Israel and in the Diaspora, over the columns of “Hamodia,” the daily newspaper of Agudath Israel, of which Rabbi Moshe Prager was one of the first founders and shapers of its image, and mainly in the monthly “Bais Yaakov” magazine; he served for 21 years as its editor-in-chief. He also greatly enriched charedi literature with his works: thoughts, stories, journalism, and poetry. He edited books of literature and anthologies for youth and adults that were published in Israel and abroad. He evocatively told the generation about the “Miraculous Rescue of the Gerrer Rebbe” and “The Miracle fo Rescue of the Belzer Rebbe.” His works have become mainstays which display a pure Jewish outlook and on whose knees thousands of rabbis are being educated, and will continue to be educated until Mashiach’s arrival.

A wonderful embodiment of Jewish vitality

We have spoken much of his literary work, and we still have not even mentioned the greatness of Rabbi Moshe himself, who himself was a victim of the Holocaust, and the tragedy of Polish Jewry burned like a fire in his bones. Until his last day, all the ideas he used as a speaker and commentator were literally embodied within him. The same scripture reads “Transgressors in the Valley of Tears make it into a fountain,” (Psalms 84:7), which the commentators interpreted in a higher sense, that is, that the Valley of Tears will turn his body into a life-changing spring, Rabbi Moshe Prager lived this line in the full depth of its meanings, first of all for himself and also for others. Who like him knew how to extract from the abysses of darkness and doom the fragments of the dew of the revival of the Jewish faith. He was like a salamander that passed through fire unscathed and continued to live.

In fact, during the terrible days, the days of extermination, he had the chance to meet on the beach of Tel Aviv a Jewish acquaintance, bereaved and tormented, who had somehow arrived in Israel straight from the cremation and was drowning in the depths of despair. Rabbi Moshe’s heart sank at the sight of him, until he grabbed him and cried out: “Oh no, isn’t this exactly what Hitler, may his name be blotted out, is plotting to do!? To break you, to force every Jew, even the one who escapes his claws and is not within his reach, to crash?! Why don’t you cooperate with him and let us carry out his plot?!”, and he didn’t let go of the man, and he didn’t let go of many others like him , until he ignited in them the burning desire to defeat the evil one and live.

And this is known to almost everyone who knew him, that Rabbi Moshe Prager used this “motto” not only in light of the Holocaust, and not only in struggles with the Satan and his collaborators, but also in all kinds of situations of suffering people who were beset by a crisis in life, and the people were engulfed in sadness, grief, helplessness. But he, the eternal friend, whose love didnot depend on anything, suddenly appeared with them, and he “hit” them on the head demandingly: “Despair – unknowingly!” – Don’t satisfy the whims of the enemy in your soul. Don’t play into his hands.

This “motto,” the surprising innovation that one serves in one’s gloomy mood to one’s opponent, did not grow from his mouth from the advice that constantly shone in his mind. Rather, it was the fruit of solid faith and a deep-rooted Jewish worldview that he drank straight from the fountain, from the house of his father and grandfather, from the Ger chassidic shtiebel (small synagogue), from the mouths of sages and writers, and most of all, from the teachings of the Sfat Emet z”l, which he would glean from all his days with eagerness and a burning thirst. The wonder spring of Jewish vitality poured forth from Rabbi Prager, watering and nourishing not only thousands of readers of all ages in many countries and languages, but also the people who surrounded him and enjoyed his conversation, Jews of all ages who came in contact with him, some for the sake of a close neighbor, and some for the sake of brotherhood, traveling by ship, plane, or by train, during his wanderings and journeys to the scattered Jewish People. Many of his children-readers who woven in their dreams the legend that the “eternal Jew” in his stories was none other than Rabbi Moshe Prager himself, were not totally wrong. There was undoubtedly a spark of the soul of the eternal Jew in him, whose adherence to the hidden root did not allow him to be trapped in the snare of failure or despair.

With a generous spirit and an evocative soul

Another shade of Rabbi Moshe Prager’s personality was his generosity, his good eye, and his kind heart. Due to the amount of attention that was, naturally, drawn to his writing and publications, or to his public activities, which will be discussed later, many did not notice his abundant kindness towards others, and the tender sensitivity that characterized this “purposeful” man. How much his heart was touched by his efforts to secretly do good for individuals, to cheer up an orphan or a widow, or to improve the financial situation of a burn patient taking care of children.

With such joy and pleasure, he rubbed shoulders with the Jews of “your people” in the chassidic shtiebel as one of them. How happy he was when he finished studying Shas (the 6 orders of the MIshna), after years of studying together with his beloved study partner, who was decades younger than him, without any distance, as a true humble person. With what admiration he lowered his eyes towards every scholar and important person, especially as he he was filled with idleness and nothingness when he stood in front of his rabbis, the Gerrer Rebbes, or other great Jewish men of their stature, and at the same time his eyes are veiled with a glistening tear of a victorious soul.

Who among us is able to dive into the depths of the evocative, poetic soul of a great writer and poet? Anyone who saw Rabbi Moshe Prager leaning over a colourful flower or a gentle stem and bush in his garden, at 33 Or HaChaim Street in Bnei Brak, as he rejoiced and was full of generosity and spiritual warmth in nurturing with the hand of faith the growing creations of G-d – anyone with a soul could have seen at that moment the great manifestations of his soul that Rabbi Prager expressed in all areas of his life, both in the rising river of his diverse writing and in his general Israeli activity.

One can be introduced to his deep emotional relationship to life and plants, combined with a deep-rooted love of the Land of Israel, through his children’s book – which is almost unknown today, and is very valuable – that he called “Nof Moladeti Mesaper Li” (My Native Landscape Tells Me.” In his short introduction to this book – which he dedicated “to the memory of my beloved Chaya, one of the million children of the exile who was consumed,” i.e. his daughter, may G-d avenge her blood – he writes touching words to his child readers: “Go out and see how great the beauty is and how great the warmth that abounds in every tree, every bud and every flower and every scrap of our dear land.”

A full ocean of emotion poured out of him with high awareness and foresight balanced as needed. His lively temper with his rest of spirit steeped in the ways of wise men was likened to brewed wine that flowed like a stream from his pen.

His part and his contribution in Torah-oriented public systems

In the above lines, his involvement in public issues is implied several times. Indeed, apart from the his writings, Rabbi Moshe Prager was a man of many actions and resourcefulness in many fields that bore a general Israeli character, but his activities were done modestly and quietly and his involvement was almost unknown. Great was his work for the Land of Israel to ensure its existence and a flourishing future for the Jewish People, which was still shaking off its ashes. He had a hand in the creation of the infrastructure and foundation of the Ponevezh yeshiva, with the initial weaving of the entire glorious Torah being, which cries out in a happiness that can be heard, and is full of life for the joy of all of us. As a confidant and person close to the Ponevezher Rebbe z”l, he was able to help him in his first steps – in the midst of the Holocaust – to give impetus to the growth of the yeshiva world.

In later years, when the British would soon be leaving Israel and preparations were being made to declare the establishment of the State, he came up with an idea and acted as the main mediator between the Jewish Agency and the leaders of Agudath Israel, who would hold talks and discuss the future direction of the State. Thanks to these talks, the agreement in principle was then signed on controlling the foundations of Judaism in the public in the State that would be established. This agreement, known as the “status quo,” guaranteed the minimum of a Jewish character in the country in the fields of kashrut and marriage, Shabbat and education (as a token of appreciation for his successful activity in this regard, Rabbi Y.M. Levin z”l gifted him a Shas Bavli [Babylonian Talmud] “as a friendly memento”).

Later, this “status quo,” was called upon to play its part in ensuring the continuity of the “Tribe of Levi” in our time, that is, to maintain yeshivas and kollels (yeshivas for married men) without interruption, based on the arrangement that the enlistment of their students into the army is postponed for the duration of their studies, as well as to freeze the plot to harm our daughters. The rest of his rights in these matters are not among the things which were allowed to be written in this world; the things were known only to the great men of the generation. They managed to find ways to the hearts of the people of authority and to persuade them to behave as they used to, and there is no doubt that everything is engraved in the notebook above (in Heaven).

The writer of the lines heard about this from the Slonimer Rebbe z”l, the “Netivot Shalom,” who was privy to matters and who greatly appreciated and respected Rabbi Moshe Prager, and he noted that Rabbi Prager was the “contact person” who served as an emissary sent from above for the rescue of Torah-learning in yeshiva. Rabbi Y. Abramsky z”l wrote about him in a telegram at the time, “You have much merit…”. Rabbi Z. Sorotzkin z”l noted his value with the words “the merit was rolled out by the one who merited it, an increase was made…” The heads of the Yeshivas Committee, who were well aware of the issue of release from conscription, considered him as the man “through whom the great salvation in Israel was accomplished.”

The Beit Yisrael’s promise: “Your world you will see in your life”

Much greatness was attributed to Rabbi Moshe Prager due to the momentum he gave to the building of homes for Torah and chassidism. In his love for Torah scholars, and in his ambition to expand the circle, he donated his private property, the lot at 15 Meltzer Street in Bnei Brak, on which the magnificent building of the “Beit Talmud Le’Horaah” for Ger chassidim was erected. He was not content with that, but instead mobilized volunteers to raise the funds for the construction of the building, and in the “Megillat HaYesod” (foundation scroll) that he wrote himself, on behalf of the founding members that he formed under his influence, he pointed out that “We are embers plucked from the burning of the Jewish People, believing with complete faith that for renewal and rebirth, G-d sent us to our holy Land, to establish in it a remnant and a continuation of the glory of the Torah that was cut off by the cursed enemies of the Jewish People. The scroll has been burned and letters are flying up, and we are ordered to collect the letters and attach them to the scrolls and revive the Torah in the Land of the forefathers.”

The dedication of his property for the “Beit Talmud Le’Horaah” was preceded by a wonderful sequence. While he was still with the besieged Jews in occupied Warsaw, Rabbi Moshe vowed that if he was saved and remained alive, he would spend his wealth on the needs of a great mitzvah. Later, when he wanted to fulfill his vow, he asked for the advice of the Gerrer Rebbe, the “Beit Yisrael” (who was very connected and close to him) and told him what he wanted to do, but the Rebbe told him “There are more vital mitzvot for you” (“for dir iz farhanden grosereh mitzvos”) – simply put and did not explain further.

Later, when the idea of establishing a kollel came up, and Rabbi Moshe z”l had it in his heart to dedicate his lot for it, it was revealed that it all stemmed from the deep advice of that sage, the Rebbe, because if he had used the lot at the time for the mitzvah he was thinking of doing, he would not be able to make the Kollel now. As he informed the rabbi of his decision to dedicate the lot to the kollel, and the voice of the Torah of the diligent students rose and played in his ears, he would whisper to himself: “Your world will be seen in your life, your world…”

In addition to this: every month, he gave scholarships to excellent scholars who would be able to study the Torah without interruption. He invested limitless efforts to expand the canvases of the holy educational movement of “Bais Yaakov,” and in particular, he supported the seminary in Jerusalem led by his friend Rabbi Pinieh Levin z”l. He even obtained sources of help to establish the existence of the “Or HaChaim” institution in Bnei Brak for sephardic girls.

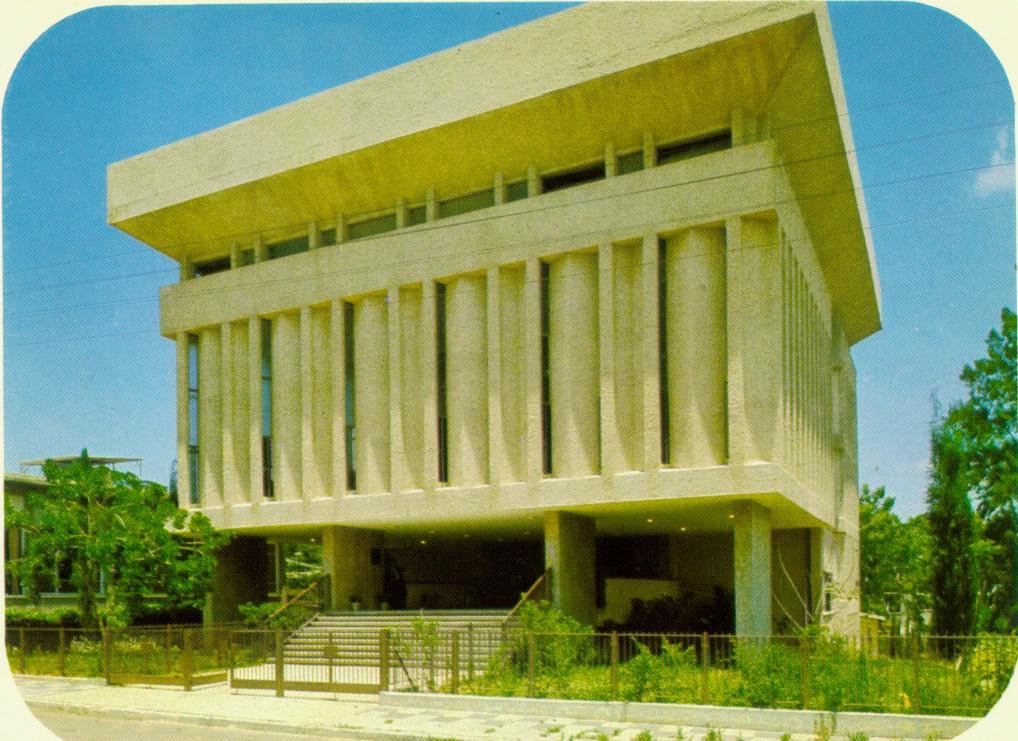

Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

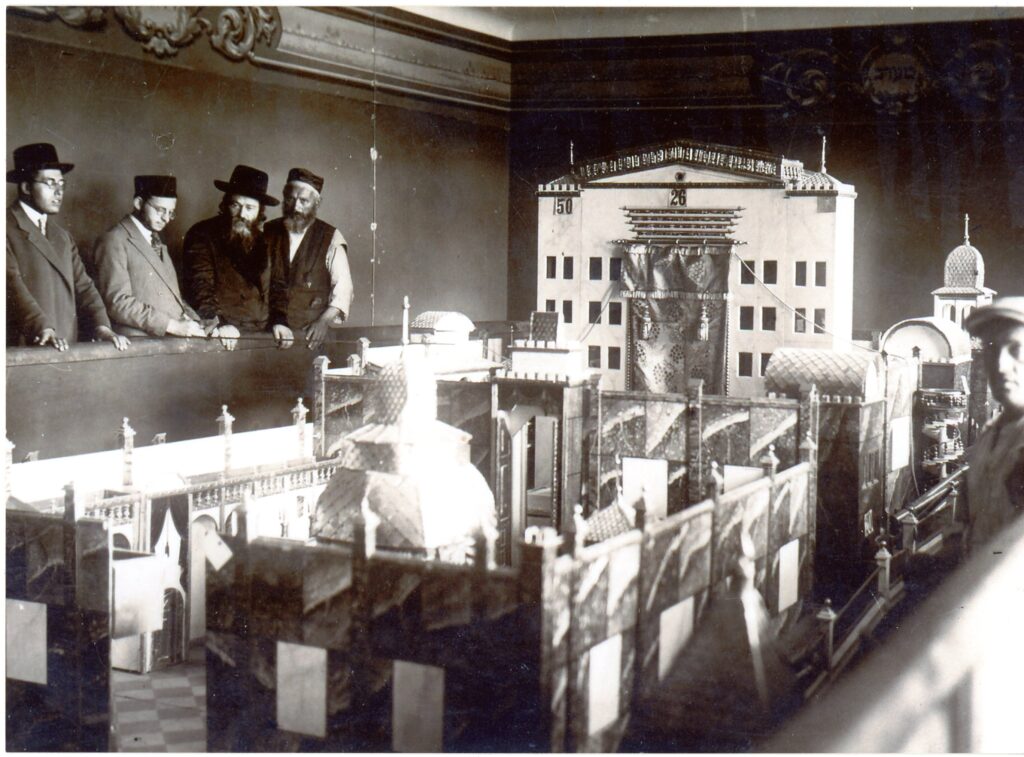

The crowning glory of his achievements and merits is perhaps rightly seen in the founding of his life’s work called “Ganzach Kiddush Hashem,” which proudly stands in Bnei Brak. This is a unique, original commemorative enterprise that exceeds in its scope and goals far beyond a normal documentary research institution intended for a purely archival purposes. Ganzach Kiddush Hashem was intended from the beginning, as its name suggests, to sanctify the Name of G-d, and not just to preserve memories of sanctifying G-d’s Name. Rabbi Moshe Prager intended to make it a distinct and highly influential educational tool that would especially permeate the consciousness of the younger generation, and cultivate the Jewish genius, deepen the roots of faith in their souls, and instill in them the fiery legacy of the sanctifiers of G-d’s Name in all generations. His ambition and great desire was to create in Ganzach Kiddush Hashem the frameworks for restoring the glory of the Jewish People and the colourfulness of the traditional, original way of life that was woven in the “world that drowned,” and in it to treasure, glorify, and emphasize all of the manifestations of the heroism of the Jewish soul in the era of the Holocaust, this against the background of research and a summary of the tragedy of the extermination.

Through Ganzach Kiddush Hashem, Rabbi Prager wanted to deepen among many circles, the consciousness of the unity of the nation and the bringing together of hearts, as well as to serve as a companion to the wonderful process of returning to Jewish roots, which he foresaw. Based on this conceptual message, he formulated a grand plan and outlined the “tools” that are supposed to contain treasures of documentary material, on any subject related to Jewish history. He believed that every matter related to the Jewish People in its diaspora, every document, every photograph and facsimile, are important to store in an accessible way and to make them useful for researchers and students – and first and foremost to save them from being lost and sinking into the abyss.

The beginning of the enterprise was unfortunate. Rabbi Moshe Prager was involved in its establishment out of a feeling of holiness, as one who pours foundations for a lofty building that will become a spiritual beacon in the future and will contribute its part to the glorification of the spirit of the Jewish People, and will sanctify the Name of G-d. Not many understood him. They were not talking about a synagogue or yeshiva. However, in his comprehensive view, modern youth needed a philosophical education, and a significant part of this education they would be able to draw from the historical and visual reservoir in Ganzach Kiddush Hashem which tells about Jewish identity in Jewish communities in the past and present, about the centers of Torah and chassidism, about struggles and trials and transformations, and at its center, of course, is the horrific event – the Holocaust.

He entrusted his life’s work to faithful hands, not least in the director Rabbi David Skulsky and his team, who according to his will ensured the continued existence of Ganzach Kiddush Hashem and even expanded its framework, multiplying its dimensions many times over. Over the years, the reservoir of the documents and photos has grown in huge numbers, and has reached thousands. The techniques of sorting and cataloging were perfected, and the doors of Ganzach Kiddush Hashem were opened to students and visitors from all educational institutions throughout the country who regularly use its services. A number of educational exhibitions have already been held at the initiative of the heads of Ganzach Kiddush Hashem, and a considerable number of professional study kits and important historical educational publications have been brought forth. According to the plan they drew up, and is in the practical stages, a new building for Ganzach Kiddush Hashem will be built in Bnei Brak on a plot of land allocated by the municipality for this purpose. It will contain halls for a library and exhibitions and for conducting educational conferences and seminars on the topics of the Holocaust and Jewish existence. In addition to a treasure trove and a huge collection of thousands of photographs and works of art on Jewish life in the Land of Israel and the Diaspora.

It is difficult to exaggerate the educational value of this tremendous enterprise, which has yet to be assigned great roles; it will bring the members of future generations closer to Rabbi Moshe Prager’s conceptual legacy. If many of the members of the present generation learned about the existence and revival from his writings, and were educated from his essays and books, there will be many more people who will come in living contact with Jewish history and existence for generations, when they come through the gates of Ganzach Kiddush Hashem, whose purpose, as stated, is to sanctify the Name of Heaven.

Taking an example from his spiritual heroism

From the generation of the sanctifiers of G-d’s Name in the ghettos and crematoriums during the Holocaust, Rabbi Moshe Prager z”l, survived and came to us, set himself a challenge to sanctify the Name in G-d in living, to serve as a guide and commentator on the events of the time, and in this way to spread the Divine voice calling to the survivor Jews “through your blood you shall live.” “with my life’s blood” (Ezekiel 16:6). On the threshold of the entrance gate to the “Beit Talmud Le’Horaah” that he founded with care and love for the students of Torah, whom he adopted as his only sons, he engraved the inscription “Were not Your Torah my occupation, then I would have perished in my affliction” (Psalsm 119:92). As you stand on the threshold of Ganzach Kiddush Hashem, the words “All this befell us yet we have not forgotten You…” (Tachanun prayer) flash before your eyes. In these two verses, a summary of the desires and feelings of the wise man are preserved, and done well.

He was almost the last of the group in Poland, the creators of charedi journalism and literature before the Holocaust, who lived and worked among us. In his life, he served as a bridge for us to the Holocaust, and who conveyed to us the ways of thinking and the language of those first writers, the bearers of the banner of faith in God and His Torah.

Following his passing 40 years ago, we only have left to refresh what he tried to instill in his readers and those around him, to collect crumbs from the remains of his desk, to preserve sparks that have not yet been extinguished from him, and above all to take an example from his spiritual heroism to not collapse under any circumstances under the burden of brokenness and grief, not to break under any circumstances, and not to despair, to remember that even when a Jew has lost his entire world, his God is alive and well: “Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil for You are with me…” (Psalms 23:4) – a verse that is repeated in his varied works.