Shana Tova Postcards from Jewish Children Studying Torah in the Detention Camps in Cyprus

By: D. Surasky

The story of shana tova postcards, Cyprus-Israel-Haifa

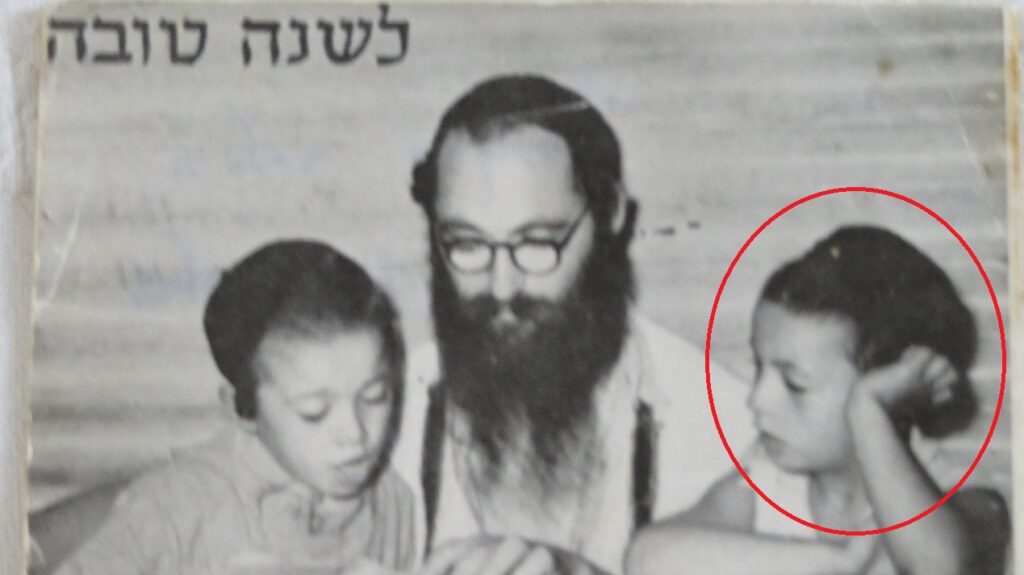

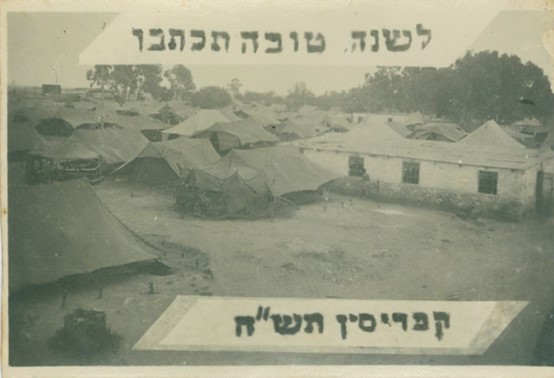

A shana tova postcard combined with a typical Jewish image, another variation of a greeting card for Rosh Hashana. This is what those who see the image before you think.

It turns out that this is what the Haifa street vendor who stood one morning offering his wares to passers-by also thought so. There was also a collection of postcards, like the one in front of us. He didn’t guess who the one hiding behind the camera lens was.

This morning was just another morning for the Popowitz family, as well as for the Haifa street vendor from whom the entire collection of greeting cards was unexpectedly purchased.

What is the story behind the picture? Who are the characters and what is their relationship? Who took the picture? And how did they get to the vendor?

Who are the cute children who study eagerly? And who are the they learning from?

Mysteries arise about the picture. Some have answers that lie in the folds of time, going back to the detention camps in Cyprus.

The cute children in the picture, the teacher in the middle, and the tin they are in are no longer a picture in the series of greeting cards.

Rabbi Ephraim Popowitz and his son Rabbi Dov Popowitz, spreaders of Torah in Haifa, were among the deportees of the “Knesset Israel” ship. As part of the fate of Bukovina Jewry, they were deported to Transnistria. Rabbi Dov was a toddler at the time.

Mogilev Podolskiy served as a concentration point for the deported Jews as well as a central and important transit point in the deportation to Transnistria.

Caravans loaded with Jewish refugees from Bessarabia and Bukovina passed through it. Between September 15th, 1941 and February 15th, 1942, nearly 56,000 Jews passed through the city. The deportees suffered from deplorable conditions in the transit camp. They faced overcrowding, filth, and abuse at the hands of the Romanian gendarmes. Thousands of Jews were expelled from the city, and despite all this, over 15,000 remained there, either due to payments and bribes or because they were considered to be an economic resource.[1] Rabbi Ephraim Popowitz and his family managed to survive the hard times in Mogilev.

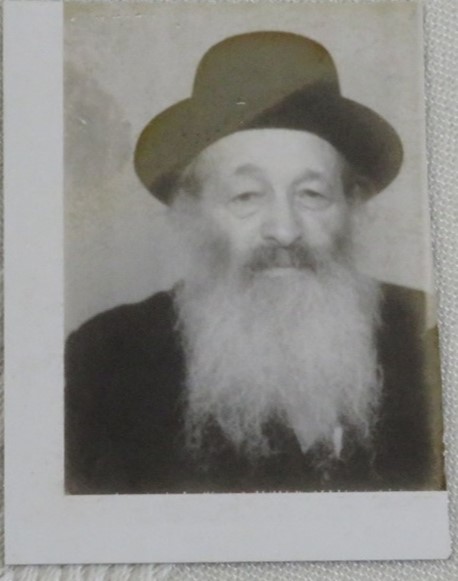

Rabbi Ephraim Popowitz (courtesy of the Popowitz family)

The fact that Rabbi Ephraim Popowitz was a furrier helped his family to survive. The residents of the area were his customers, and thus the family survived, albeit with great difficulty. The mother of the family perished from the typhus epidemic which was a permanent fixture of the area.

In November 1946, with much hope, they sailed on the ship “Knesset Israel.” In the testimony given by Rabbi Popowitz, he shared his experiences, that were burned into his memory as a 6-year-old boy, from the harrowing journey, about the living conditions and the overcrowding on the ship [2]:

“This ship was not for people, it was for packages… they installed shelves on the ship, and loaded people. I couldn’t even sit straight on the shelf as a child…”

“The ship was big, when there was a storm at sea it shook a lot… They made a minyan (quorum of 10) for prayer.”

“I remember very well the burning of the tear gas used by the British during the struggle in the port of Haifa.”

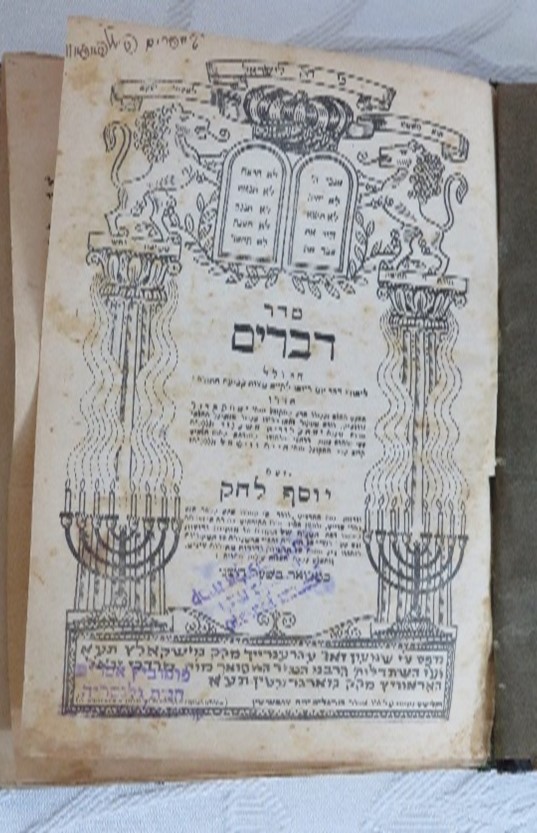

The new reality of life in Cyprus welcomed the refugees. Living in poverty, in overcrowding, in shacks that sweltered in the summer and with sparse food. Each refugee had one backpack in those days; in the backpack of Rabbi Ephraim Popowitz was the “Chok Yisrael” Chumash (Pentateuch).[3] The volumes of the Chumash went on all the rabbi’s trips with him, and he watched over the volumes closely. Even when posessions were thrown from the ship, they remained with him. Rabbi Ephraim Popowitz was a learned Torah scholar. In the detention camps, he was a “wealthy man” with his valuable treasure. The inmates of the camp suffered from poverty and the lack of basic holy books. This is how he began to study with partners.

In his “Chok Yisrael” Chumash, Rabbi Ephraim Popowitz added in the memorial days for his family members (courtesy of the Popowitz family)

But beyond that, the father was concerned with the education of his child, Rabbi Dov. The child’s inactivity and idleness particularly bothered him.

The above photo was taken by the photographer in the detention camps in Cyprus. The tin shack that adorns the picture leaves no doubt as to the location where the picture was taken. In it, Rabbi Dov (on the right) is seen studying Torah, and who is in the middle?

- Rabbi Moshe Yeshaya Berkowitz, a pioneer Torah educator: “May the simple ones rejoice, may the students rejoice, may the supporters rejoice. On Simchat Torah” (a Simchat Torah song). [4]

Among the passengers of the “Theodore Herzl” ship who arrived in Cyprus immediately after Pesach 5707 (1947) was Rabbi Moshe Yeshaya Berkowitz. Even during the ship’s voyage, he stood out for his resourcefulness and willingness to help with all necessities. Rabbi Shmuel Kaufman, who was with him on the voyage, testifies: “Rabbi Yeshaya stood in the kitchen all day and made sure that no one lacked anything. He would volunteer for the task and carry it out perfectly.”[5] The situation of the youth in the absence of a framework touched the heart of Rabbi Shimon Benisch. Already in the displaced persons camps in Germany he was among the pioneers in establishing educational establishments, and in Cyprus he was also one of the activists. His first educational enterprise was the establishment of a yeshiva in Camp 64, in the “winter camps” under the presidency of the rabbi of the detention camps, Rabbi Y. Bentzion Rotner. But the younger classes and the middle classes of the children remained unorganized. This fact was an impetus to establish a Talmud Torah school. “I started searching through the camps, and in the first phase I gathered about ten children from religious families, and now I had to find a teacher who would dedicate himself to them and teach them to read and write. The addressee was Yeshaya Berkowitz, who besides his kindness was also gifted with ironclad patience. And he is indeed willing.” [6]

And so, along with other children, Rabbi Dov was one of the students of the Talmud Torah. It is true that his father, who was very involved in learning, taught him as well, but the Talmud Torah school and his studies with Rabbi Berkowitz heald special meaning and purpose for him. The cradle of his Torah world was at the Talmud Torah. Later he was sent to the Vizhnitz Yeshiva in Haifa, and then to the Ponevezh Yeshiva in Bnei Brak.

Rabbi Ephraim Popowitz’s chanukia which accompanied him thoughout his journey, and now graces the home of is son, Rabbi Dov, in Haifa (courtesy of the Popowitz family)

Children learning Torah. An eye-catching reality in the detention camps also caught the (unknown) photographer’s eye and entered the camera frame, with Rabbi Berkowitz documented in the photo.

- “The art of life” behind the barbed wire fences – creation, photography, and crafts

In the circles of day-to-day life in the detention camps, a system of creation, crafts, and art of various kinds developed. “Necessity,” the mother of invention, was the initial motivation. The lack of clothing and footwear, tools, basic elementary life necessities were a primary fundamental factor for the development of crafts and the popular creation of “useful art.” Clothes were sewn from the tent fabric, an iron was made from a tin, and a fire pit was created from a tin can. The raw materials in the camps were the basis and the source of the fruitful creation, a breakthrough for any imagination that has no match. The food boxes, the ropes of the tents, the blankets, as well as the camp facilities such as the soft stone floor, formed the basis for a multi-faceted and colorful creative arc, far beyond their initial use. On the one hand, they were used for useful amateur creations, a unique method for solving problems, and on the other hand, for folk artistic creation of decorative objects, drawing, illustration, painting and sculpting, a new kind of factory for creation and art. Beyond that, an organized professional training system of creative and artistic workshops, organized by bodies such as the Joint, also developed. Art workshops were integrated into the education systems and youth movements. “Rotenberg Seminar for Teachers” was an institution that operated art classes for adults.[7] Among the deportees from Cyprus there were also artists with professional backgrounds. During their detention in Cyprus, they drowned their experiences in works of art. Cyprus was a stop for them and the spark of their development. Among the well-known artists, we can mention Shraga Weill and Abba Fenichel.

In the realm of fruitful creation, we can include the prosperity of photography, which ranges from art to craft. Photography workshops operated in the detention camps, which were also part of trade.

Of the businesses established in the Cyprus camps, the photo shops operated by the illegal immigrants are particularly noteworthy. The photography workshops, which stand on the border between craft and art, document the daily life in the camps.

The photographers photographed groups and families privately, but also documented public events and scenes from camp life. These photographs were sold as souvenirs to the illegal immigrants and emisaries…[8]

“Photo Rachel” was one of the well-known photography workshops, and was operated by Rachel Fisher. Already in her childhood as a photography enthusiast and before the war, she worked at “Photo Brand,” photographing, developing and retouching photographs in her hometown of Kolozsvár.

Upon her arrival with the illegal immigrants of the “Pan York” ship (in January 1948), she opened a photography shop, “Photo Rachel,” which is what was written on the sign in front of. [9]

“Within a few days, we set up a dark room in the nearby tent… where I would develop the pictures. A Cypriot young man of Greek origin smuggled me paper and development chemicals from the city of Famagusta. I painted a kerosene lamp red.” [10]

A combination of factors shaped the creative works, their spirit and the cultural environment of the illegal immigrants and they are present in the works and are a source of inspiration. The perception of the reality of those imprisoned in captivity, the events of the Holocaust and their stops in ther journeys, the experience of illegal immigration alongside the Jewish tradition and faith and its symbols, commemoration and remembrance of family members and communities, the longing for the Land of Israel and Jerusalem – all these are embedded in the works. Judaica was one of the treasures of the works. The cycle of the Jewish year is reflected, alongside landscape paintains of Cyprus.

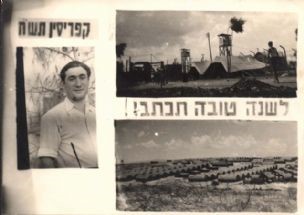

An ancient Jewish custom that began in the Middle Ages in Ashkenaz is sending greeting cards. From there it expanded and took shape over the years, and did not pass over the creative spaces in Cyprus. Quite a few postcards and greeting letters have been preserved in different variations and techniques, such as photomontage (combination of several images in a photograph), combination of illustrations, typography, and graphics. Along with shana tova greetings from the prisoners, their prayers and dreams were evident in them. The illustrations and photos portrayed a picture of their lives and their situation, and even expressed their hopes…

“Some of the photographers also specialized in “shanot tovot” (shana tova cards) photos prepared using the photomontage technique. The photographers chose photographs and drawings of rows of tents, the tin huts, the watchtowers, the bridge over the gravel road between the camps, the illegal immigration ships off the coast of Israel and its scenery and “handshakes” between the Holocaust refugees in the Cyprus camps and the residents of Israel – which was being built and was growing – and combined them in “shanot tovot.”[11]

A greeting card for the New Year sent from the detention camp in Cyprus, bearing pictures from the camp (Ganzach Kiddush Hashem archive)

A photo of a detention camp in Cyprus with the phrase “LeShana tova techateivu” (may you be written in for a good year) written on it (Ganzach Kiddush Hashem archive)

The postcard in question is a product of photography in Cyprus. Many questions about it are still unresolved. Who took the picture? How did it end up in Israel? How and by what means? And who duplicated the postcard that was sold?

It may also be one of the greeting cards created in Cyprus.

There are many questions, but one answer stands out to those who look at the picture beyond what is captured in the photographer’s eye: Jewish children continue to study Torah. One picture and many are depicted in this context, even though they were not in the camera’s focus:

“There is no honour like the Torah. And there are no students as Israel (the Jews) – From the mouth of G-d, Israel will be blessed” (a Simchat Torah song)

[1] I. Gutman (editor), “The Encyclopedia of the Holocaust,” Yad Vashem, Vol. 3, pg. 668.

[2] From an interview conducted with Rabbi Popowitz. Thanks to the Popowitz family for the assistance in obtaining the information and its accuracy, and for transferring the documents and photos.

[3] Chok LeYisrael: “A daily study schedule that includes reading Torah verses, Prophets, and Writings, studying a Mishna chapter, and passages from the Gemara, a book of Halacha and a book of the Zohar. The order of study is based on what the Ari z”l used to do…”

[4] The source of the initial information about the postcard and its background are found in Rabbi C. Benisch’s book, “Ish Lehava: D’mut Diukeno u’Masechet Chayav HaMuflaa shel Sarid HaKavshanim, HaRav Shimon Benisch z”l, Ish Chai Rav Paalim,” chapter 25, 5775 (2016-7), pg. 360–364. I based the material on what was written there.

[5] Rabbi Benisch, ibid., pg. 360.

[6] Ibid.,

[7] Y. Kaufman, “Malacha V’Omanut Amamit BeMachanot HaMe’atzar LeMaapilim BeKafrisin (1946-1949),” essay for obtaining a “certified humanities and social sciences” degree, Ben Gurion University, 2019. My thanks go to Y. Kaufman, the director of the information centre “Benitivey HaApala” – Atlit, for the assistance and guidance in research and the sources of information. This study serves as a basis and source of knowledge for me.

[8] Ibid., pg. 10.

[9] https://hope.eretzmuseum.org.il/photographers/%D7%A4%D7%99%D7%A9%D7%A8-%D7%A8%D7%97%D7%9C, Muza – HaBayit LeTzilum: The center for documentation and research of local photography

[10] Raz G. (exhibition catalog), “Photo Rachel: Tzilumim MiMachanot HaMeatzar BeKafrisin, 1948-1949,” Eretz Yisrael Museum, 2011, pg. 64.

[11] Feldman N. “Bracha Lach Moledet M’Ever LaTil: Shanot Tovot U’Mizkarot MiMachanot HaMe’atzar BeKafrisin,” Et-Mol, 252 (2017), pg. 19.