Would You Give Away Your Bread in a Concentration Camp?

By: Rabbi Dovid Campbell, Originally printed on Aish.Com on May 7, 2023

In the dark pits of hell, Rabbi Gershon Liebman somehow managed to spread his light.

Life in the concentration camps was inherently dehumanizing. The work was crippling, the hunger was unimaginable and the threat of death was constant. Under these conditions, it was difficult to focus on anything but survival. The young Rabbi Gerson Liebman, who would eventually become a powerful force for Jewish education in postwar Europe, quickly recognized the great need to preserve his sense of humanity.

Throughout his time in the camps, he maintained the practice of never eating his entire meal at once, always leaving some food on the plate. This simple action reminded him that he could still behave with refinement and moderation, even here. In a place where people swallowed whatever food they could find, as quickly as they could find it, it seemed absurd to bother with something like this. But Rabbi Liebman refused to be dragged down by external circumstances, no matter how hellish they were.

A similar story is told by Rabbi Yaakov Galinsky, who survived the Soviet labor camps in Siberia. Early one morning before the other prisoners were awake, Rabbi Galinsky awoke to a strange sight – an older Lithuanian prisoner was quietly donning a military uniform that he had hidden in a work satchel. Complete with impressive ribbons and medals, it was the full-dress uniform of a Lithuanian general. He began to quietly bark orders and salute the air. He returned the uniform to his satchel when the other prisoners began to wake.

Rabbi Galinsky couldn’t contain his curiosity. The Lithuanian was initially embarrassed to have been seen, but he eventually explained: He had been a general in the Lithuanian army, a decorated military hero with tens of thousands of soldiers under his command. Then the Soviets came and it had all disappeared in an instant. “They sent me here into exile, to this miserable hole, and they’re doing everything they can to turn me into a wretched prisoner so that I’ll forget my former glory. But I don’t intend to forget!”

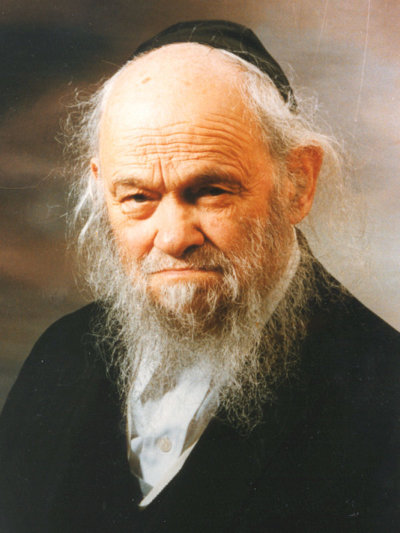

Rabbi Gershon Liebman z”l

Rabbi Galinsky absorbed a powerful lesson from these words – the same one Rabbi Liebman embodied with his small plate. Circumstances might rob us our comfort, our glory, or even our basic human necessities, but no circumstance defines our self-worth. We can always remind ourselves of who we are, using the mirror of our own proper conduct.

Pass the Bread

Rabbi Liebman would often share his bread with other prisoners, nursing them back to health from the brink of starvation. It’s difficult for us to understand what an enormous sacrifice this was. Imagine a patient suffering from pneumonia, struggling to fill his lungs with air, who nevertheless chooses to share his oxygen tank with others. The small daily ration of bread was their tenuous link to life.

Howard Schultz, CEO of Starbucks, recounts an unlikely encounter he had with Rabbi Noson Tzvi Finkel, the head of the Mir Yeshiva seminary. Rabbi Finkel wanted to convey the Holocaust’s enduring lesson for our times, and he did so by portraying the Jewish prisoners’ first night in the camps:

“As they went into the area to sleep, only one person was given a blanket for every six. The person who received the blanket, when he went to bed, had to decide, ‘Am I going to push the blanket to the five other people who did not get one, or am I going to pull it toward myself to stay warm?’ It was during this defining moment that we learned the power of the human spirit, because we pushed the blanket to five others.”

As Rabbi Finkel concluded his meeting with Mr. Schultz, he told him, “Take your blanket. Take it back to America and push it to five other people.”

In the midst of unimaginable hardship, when we would expect individuals to be at their most selfish and cruel, we discover what we are truly made of. Rabbi Liebman took himself out of the picture and focused on the needs of others.

Find a Reason to Try

In the Buchenwald concentration camp, it was not unusual for the prisoners to succumb to starvation and exhaustion. The Nazis would place their bodies in a designated room until they could be buried the next day. But Rabbi Liebman suspected that some of these poor souls were not actually dead. Risking his life, he crept into the pitch-black room at night and, crawling among the bodies, searched for signs of life.

Sometimes he would feel warmth in a body, awaken the man, and help him back to his barracks. On one occasion, a body seemed totally dead, but Rabbi Liebman felt a small tremble in the man’s lip. Not knowing the man’s barracks, he brought him back to his own, where he massaged the man back to consciousness. But he was still too sick to be moved and this created a terrifying problem.

Officially the man would be listed as dead, and there were now the wrong number of prisoners in the barracks. Additionally, he would no longer receive food rations. Rabbi Liebman and the other prisoners chose to hide him and feed him from their own meager rations. The man survived and was eventually reunited with his wife after the war.

There were so many reasons not to attempt these nightly rescue missions, but Rabbi Liebman was looking for the opposite: He wanted an excuse to try, and he found it in even the smallest tremble of life.

Whether saving a single soul or pioneering Jewish education after the Holocaust, Rabbi Gershon Liebman embodied the beautiful words of Anne Frank: “How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.”

About the author: Rabbi Dovid Campbell lives in Ramat Beit Shemesh with his wife and children. He is the creator of NatureofTorah.com, a project exploring the Torah’s role in revealing the moral beauty of the natural world.