“All the People of Israel are responsible for one another.” Even amid the devastating and difficult reality in which the Jews of Europe lived during the war, there were many who mobilized to help the weak among them and those in need - whether by means of entire charitable organizations established for this purpose or whether by means of private acts of relief and help from one person to another. As the years go by, we are exposed to more and more documents about the extent of mutual aid and res...[Read more]

“All the People of Israel are responsible for one another.” Even amid the devastating and difficult reality in which the Jews of Europe lived during the war, there were many who mobilized to help the weak among them and those in need - whether by means of entire charitable organizations established for this purpose or whether by means of private acts of relief and help from one person to another. As the years go by, we are exposed to more and more documents about the extent of mutual aid and responsibility during the Holocaust. It seems that there is not a single Holocaust survivor who did not encounter help and an outstretched hand from another Jew. Here is a collection of testimonies and exhibits from the repository of Ganzach Kiddush Hashem, which describe the mutual responsibility and the emotional and material relief that the members of the Jewish people provided to each other during the Holocaust.

Rabbi Sinai Adler – A Lesson in Faith (Prague, Czechoslovakia)

Lonely But Not Alone

Lonely But Not Alone

An open miracle happened to me on one Shabbat. When I arrived at work on Shabbat morning, I immediately prayed the Shabbat day prayers, after that, fatigue took over me and I decided to rest a little. In the yard there were usually closets, next to each other. I went into one of the closets, and fell into a deep Shabbat sleep.

At ten in the morning, a by German officers suddenly arrived for an inspection, but I was not aware of the "visit" at all because I was deep in sleep. Suddenly the closet opent and I see a group of German officers in front of me…I went completely pale.

Human nature is that when one is awaked suddenly, his face will go very pale, but all the more so when the awakeners are Nazi army officers…

Fortunately for me, the Jewish guard in charge of us was standing with them, and at his own risk he said to them: This guy was not feeling well, he turned to me and I gave him permission to rest here. The Germans were satisfied with his answer, and continued on their way… Miraculously, the incident ended peacefully, because normally one would be killed for such an offense. The kindnesses of G-d never cease! Indeed, His mercies never fail!

Our foreman received a special order one day: locating a certain piece of furniture for a Gestapo man named Brand. Anxiety mixed with curiosity accompanied us when we brought the furniture to his home. When we appeared at the door of the house, he received us with respect: it turns out that he was in charge of Judaica objects; we concluded this since his house was full of Jewish silver items, and in his personal office there was a small silver ark with a Torah in it… "For this our heart has become faint, for these things our eyes have grown dim"…to see the ark and the Torah in captivity, in exile - in such an unclean place.

Since I was working outside the ghetto, I got lucky and was able to smuggle food to the starving ghetto residents. It was a great danger, and many perished when they were caught with smuggled food in their bags. My Jewish family's ties with our gentile neighbors stood out to me at this time: a Polish gentile, who before the war worked as a building guard where we lived helped, me and exchanged food with me for material. I brought the material from a warehouse where goods from the family's store were hidden, and in return I received bread, milk, eggs, cheese, and even vodka. We got along very well. The Jews had temporary well-being.

(A Mother's Prayer, Natan Ginzberg)

Jews in line to receive assistance from the Jewish Self-Help Organization in Warsaw

Faiga Leah Bolak – Assistance and Aid in the Lodz Ghetto (Lodz, Poland)

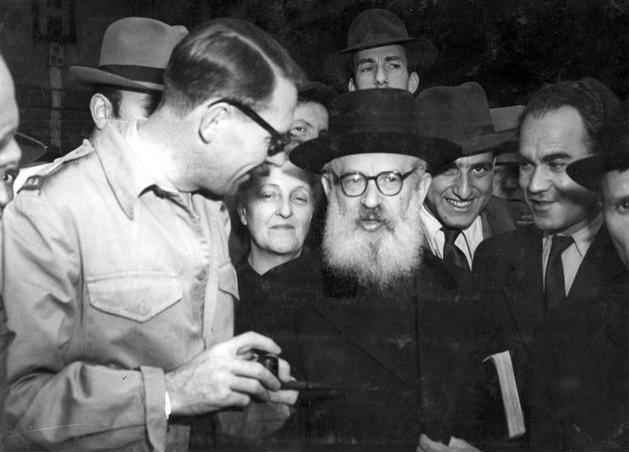

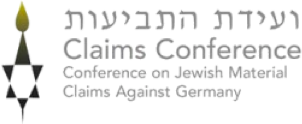

Rabbi Yitzchak Herzog at a meeting arranged in his honour in Prague, with members of the UNRRA relief organization

Esther Horberg – Mutual Aid in the Labour Camp (Krakow, Poland)

An elderly couple receive aid from the Jewish Self-Help organization in the Warsaw Ghetto

Poria Sokal – Mutual Aid with Self-Sacrifice/The Death March (Warsaw, Poland)

Aid packages being put together in the Joodse Raad (Dutch for Judenrat, Jewish Council) in Amsterdam

Chava Drenger – Mutual Aid in Auschwitz (Poland)

Members of the Malbish Arumim (Clothe the Naked) Organization in Chelm, Poland

Gita Cycowicz – “Living Waters” (Chust, Czechoslovakia)

The dining room for child refugees inside the Jewish Italian aid organization, Delasem, in Milan

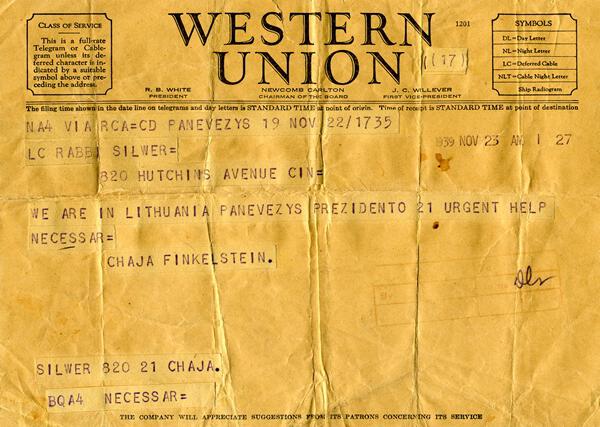

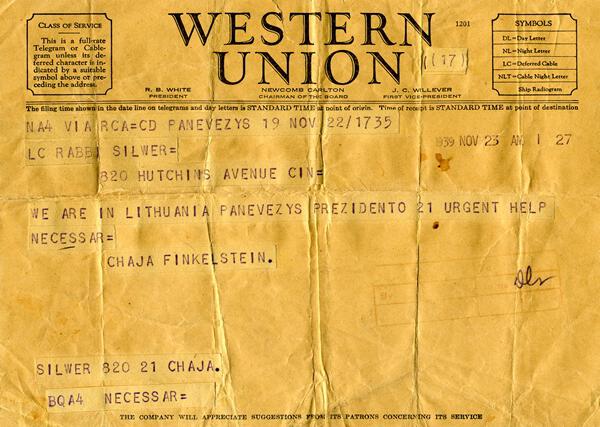

A telegram sent to Rabbi Eliezer Silver by Chaya Finkelstein from Ponevezh, Lithuania, turning to him to ask for help

Dov Silber – Hospitality with the Outbreak of the War (Piotrkow, Poland)

Jews waiting in line to receive food in the Warsaw Ghetto

Survivors Jews dine at the kosher kitchen established by Committee of the Religious Jewish Community in Czestochowa, Poland

“Send Forth Your Bread Upon the Surface of the Water”

“Send Forth Your Bread Upon the Surface of the Water”

In the first months, my friends and I worked as simple labourers in the camp. It was hard work, where we loaded or unloaded the cargo from the train cars. The work started at 6:00 in the morning and continued continuously until 6:00 in the evening; we ate a small slice of bread in the morning and at noon we received a plate of soup. I had not yet returned to normal after the illness that attacked me in the Blizyn camp. I knew that in this situation, I would not be able to last. A week will pass, maybe two weeks, and I will be like those unfortunates who lost their souls, as a result of the hard work and severe hunger…

Jews from France were also brought to Auschwitz, from them we learned that the Nazis had invaded their homeland. And it occurred to me to search, maybe I'll find someone familiar, maybe one of my uncle's families living in France. Indeed, I met a Jew from France, and I was amazed to hear how the conversation flowed out of his mouth in the "Mama Lashon," Yiddish in a Polish dialect. He corrected me by explaining that he was a Polish Jew, he was even one of the reporters in the newspaper "Moment" published in Warsaw. In the first days of the war, he fled from Poland to France, where he fell into the hands of the Germans. When he heard my family name, he was excited to hug and kiss me for a long time. "It's a small world," he concluded. I was dumbfounded at the sight of his enthusiasm. "Is Deutscher who lives in Paris a relative of my family?" He asked and did not wait for an answer, "Know that I owe my life to this Deutscher!"

"I wandered and wandered throughout France, an exilee without anyone who knew who was aware of me. Until I chanced upon your uncle's house and he, with the his big heart, opened his door wide for me. I lived in his house for many months, until the day the Germans caught me and sent me to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where I have been for almost a year."

The luck of this French-Polish Jew improved and he was one of the people who worked in "Kanada," the Jews who took the Jewish arrivals to Birkenau off the trains.

There was no lack of food for him, and he brought me a whole loaf of bread every day, from which I and ten other Jews who shared my portion with me subsisted. This practice continued even after I moved to a workplace where the conditions were more benign.

I received a whole loaf of bread from him - a "treasure" in Auschwitz terms - every day, from which a number of other Jews were fed. This is what the wisest of all people said: "Send your bread on the surface of the water, because on most days you will find us." Thanks to my uncle's "bread", I was saved. After half a year - I had to help this Jew, whose life turned upside down, his conditions deteriorated, he was transferred to a worse camp and his bread was broken.

(The Candles that were Not Extinguished, Mordechai HaKohen Deutscher)

Frieda Schiff – Hosting Guests in Romania (Bielec, Poland)

A child supporting an elderly blind man in Lublin

Children eat in the kitchen of the Agudath Israel orphanage at Twarda 21 in Warsaw, Poland

Yehudit Rubinfeld – “Der Shvester Lager” (Camp Sisters) (Lutynia, Hungary)

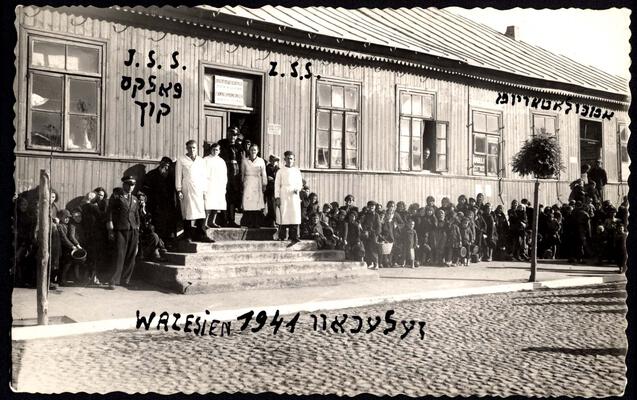

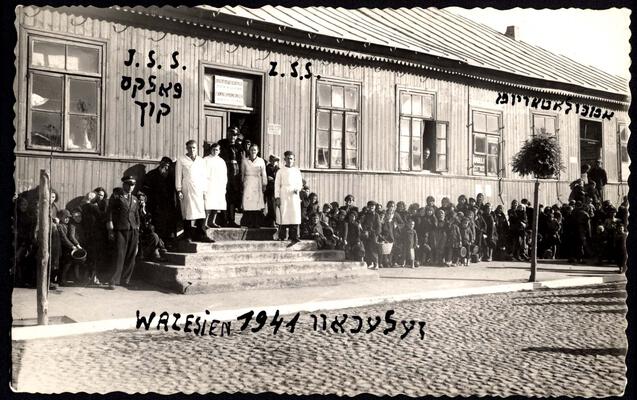

Children and staff at the entrance of the barrack used as a public kitchen in Zelechow, Poland

Yehoshua Eibishitz – Work on Yom Kippur (Wielun, Poland)

Girls in the dining room in the orphanage in Czestochowa

Yehudit Rubinfeld – Giving and Support in the Bergen-Belsen Camp (Lutynia, Hungary)

An illustrated poster of the Jewish Self-Help organization in the Warsaw Ghetto

Nachman Sonabend, a postal worker in Lodz, distributing aid packages to the needy

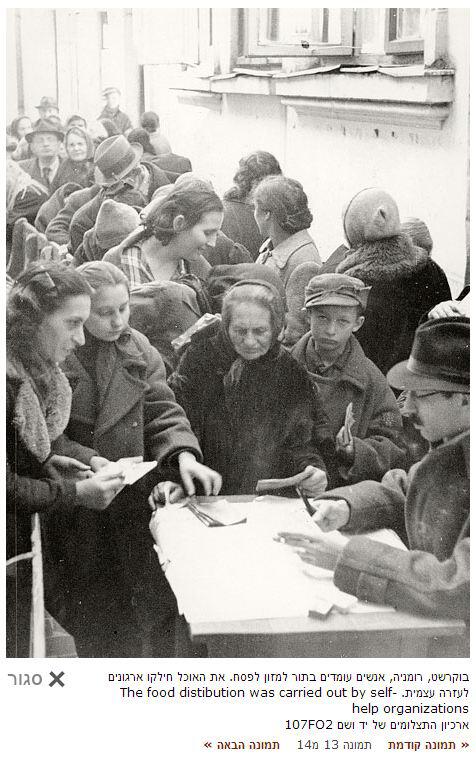

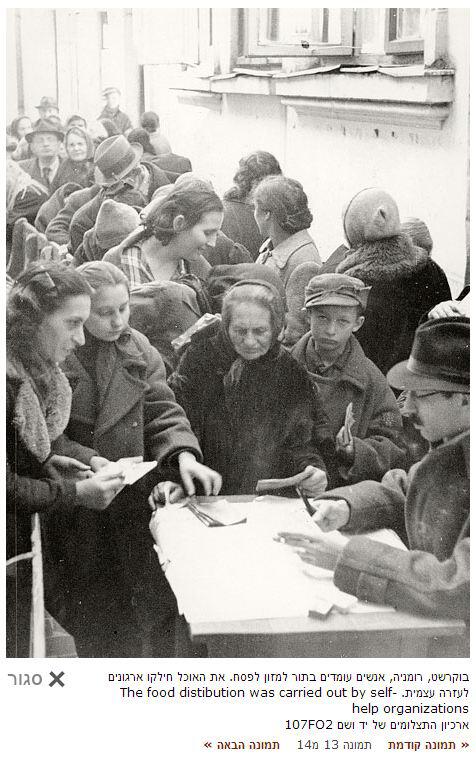

Jewish refugees in Bucharest wait in line to receive food for Passover

A line of people waiting for food in the Warsaw Ghetto

A Roll and Herring

A Roll and Herring

Their day began with the sharp cry of the wake-up alarm that propelled them from their bunks. Shivering under their shabby work dresses, the girls and women would run to the Appelplatz (roll call ground) for the predawn roll call, as the prolonged screech of the alarm continued its assault on their ears.

Lining up for roll call was the same every day: standing at attention, motionless, for no reason other than to humiliate them and leave them open to any sort of sadistic abuse that struck the fancy of the commander, who strutted between the rows swinging his whip.

One morning, it was pouring rain, but they had to stand there as usual, in perfectly straight lines, with the rain beating on their faces, soaking their dresses, and chilling their emaciated bodies. Mama stood there, silently murmuring the Morning Blessings, as she did every day. She had no siddur (prayer book), and davening (praying) the whole morning service was impossible; it belonged to another time, another world where life was normal. Here, there was nothing to life but staying alive for one more day. But every morning, Mama said Birkos HaShachar (the Morning Blessings) under the nose of the Nazi with the whip. No one could take the Divine spark of her soul from her, and that short segment of the daily prayers was a window through which its light shone.

That morning it was harder. It was very cold, and she was soaked through. The ground under their feet had turned to mud, but the commander went on as usual, up and down the rows, abusing the young women as if they weren't suffering enough.

Mama recited the blessings silently, and just when she came to the brachah (blessing) of "shelo asani goy" (that G-d did not make me a gentile), the Nazi passed by her. He was well protected from the rain in his long, heavy coat, his polished boots, his officer's cap, and his gloves. He had everything they didn't have. He embodied power and strength, while they were defenseless, weak, and exposed.

But Mama looked him in the eye, through the pouring rain, thinking for an extra moment about the brachah she was about to say. What a blessing not to be a gentile like that one, even with all his power, strength, and splendid uniform! Suddenly, fear left her, and she was filled with clarity.

The rain continued beating down on their heads, filling their dresses with water. But Mama was lifted above all that. She was above this Nazi, with his bloodthirsty eyes and his whip. She was drawing in all his strength. She felt nothing but scorn for him, and nothing but pride that she was not in his place, striking out at young, defenseless women. "Baruch Atah Hashem...shelo asani goy" (Blessed are You G-d...that you did not make me a gentile).

♦

The terrible hunger that raged in the camp brought on an epidemic of typhus that ran wild through the barracks, snatching young women and leaving them to die in the absence of any proper medical care.

Mama caught the infection too. Burning up with fever, writhing in pain, and half-conscious, she was taken to the infirmary. In the bed next to hers lay another girl, delirious with fever and mumbling unintelligbly. The high, uncontrolled fever cause strange delusions. Suddenly, the girl turned to Mama with glassy eyes and said clearly and eagerly, "Could you please get me a roll and some herring? I've just got to have it, a white roll and herring. Please!"

A white roll and herring? She must have a very high fever and a lot of imagination to be asking for something like that. She might just as soon have asked for the moon.

Mama began to recover, which was a miracle, since she wasn't getting any medicine. She went back to Rutka and her other friends, weak and shaky, but out of danger. The strange request of the girl in the infirmary retreated to the back of her mind.

A few hours later, some items were thrown over the fence that separated their camp from the men's camp and landed on the ground near them. The men didn't have any better conditions than the women, but sometimes if a man managed to steal or barter for some extra food, the thought that his wife, sister, or daughter might be on the other side of the fence moved him to toss it over to the women's side. There were certain times of day when the Nazis weren't watching closely and the "mail delivery" took place.

Mama went over to the fence when she noticed the first items flying over, and suddenly a little bundle landed at her feet. She picked it up, opened it, and froze in disbelief. It was one white roll and a little packet of herring.

The image of the girl in the infirmary rose up before her. She saw the pleading eyes, glassy pools of suffering.

According to the rules, she was supposed to share her prize with her closest friends. It was an unwritten, but sacred law. Everyone shared; that was the only way to survive. And her friends were looking at her expectantly. But Mama made a special appeal to them: "There's a girl in the infirmary, and she asked me for a roll and herring today. And of all things, that's exactly what I found her! It might be her last request. We must give it to her!"

"You're not being rational," they told her, their eyes flashing hungry fire. "That girl is dying, and this food won't save her. But it could save us!"

But Mama didn't see it that way. How could it be that a roll and herring, of all things, had just fallen at her feet, if it wasn't meant for that poor, sick girl? "We wouldn't dream of asking for something like this," she said. "And we certainly would never expect to get it. But that girl, in her delirium, asked for precisely this. Her last request! How can we refuse?"

Mama won the argument. She went to the so-called infirmary, where the sick were left to get well miraculously or to die, and with trembling hands she offered the little meal to the dying girl. The girl took it in her hands, not sure whether it was real or part of a hallucination.

That was Mama.

One day, many years later, someone told Mama that Malka Wolf from Bnei Brak had sent regards. "Malka Wolf?" Mama scrolled through her memory, trying in vain to remember someone by that name. No, she didn't know any Malka Wolf. The regards must have been meant for someone else.

And then one day, Mama herself was in Bnei Brak, and a lady of impressive bearing came over to her. "I'm Malka Wolf," she said, almost choking with emotion. "Don't you recognize me?" Mama gazed at the woman's face for another moment, and suddenly, she recognized the eyes. Big, blue eyes...a high fever...Hamburg...delirium...a roll with herring.

"Is it you?!" Mama grabbed her by the shoulders, as if to verify that she wasn't seeing a ghost. "You mean you survived?!"

"Yes, it's me. I had techiyas hameisim (revival of the dead). The shadow of death was closing in on me. I felt my life running short, like the last bit of sand in an hourglass. And then, suddenly, a hand reached out to me, breaking through that dark fog - a hand bringing me a roll and herring. I held that roll in my hands, and I felt new strength flowing into me. It came from knowing that someone had thought of me...someone saw me...someone heard my cry...someone cared...and suddenly I knew I could make it...I knew I deserved to live...and I began to get well.

"I don't know how you got that roll and herring. It was surely a miracle, and many more miracles got me through the rest of the war, and all this time I've been searching for you. I found out your name, but I didn't know where you were. And now, finally, I've found you!"

Mama's eyes were full of tears. "I was surely going to die that night," said Malka. "When you came to me with that little package, that was the turning point. I owe my life to you."

(How Could I Not Have Known?, Chana Rotenberg)

Members of the “Gemach (Loan) Committee” in Sierpc, Poland

Sarah Geiger – Taking Care to Respect Parents (Lodz, Poland)

Abba Halperin – Auschwitz (Lithuania)

Children ritually wash their hands before eating in the public kitchen for children run by the CENTOS aid organization at Penska Street 29 in Warsaw

Devorah Berger – An Apple in the Camp (Lodz, Poland)

The food distribution line at the public kitchen in the Ostrowiec Ghetto

Yosef Dzialowski – A Lesson in Faith in a Labour Camp (Lodz, Poland)

Jews dining at the soup kitchen in Warsaw, Poland

Poria Sokal – “Camp Sisters” – Majdanek (Warsaw, Poland)

Uri Teitelbaum – In the Train on the Way to Auschwitz (Hajdunanas, Hungary)

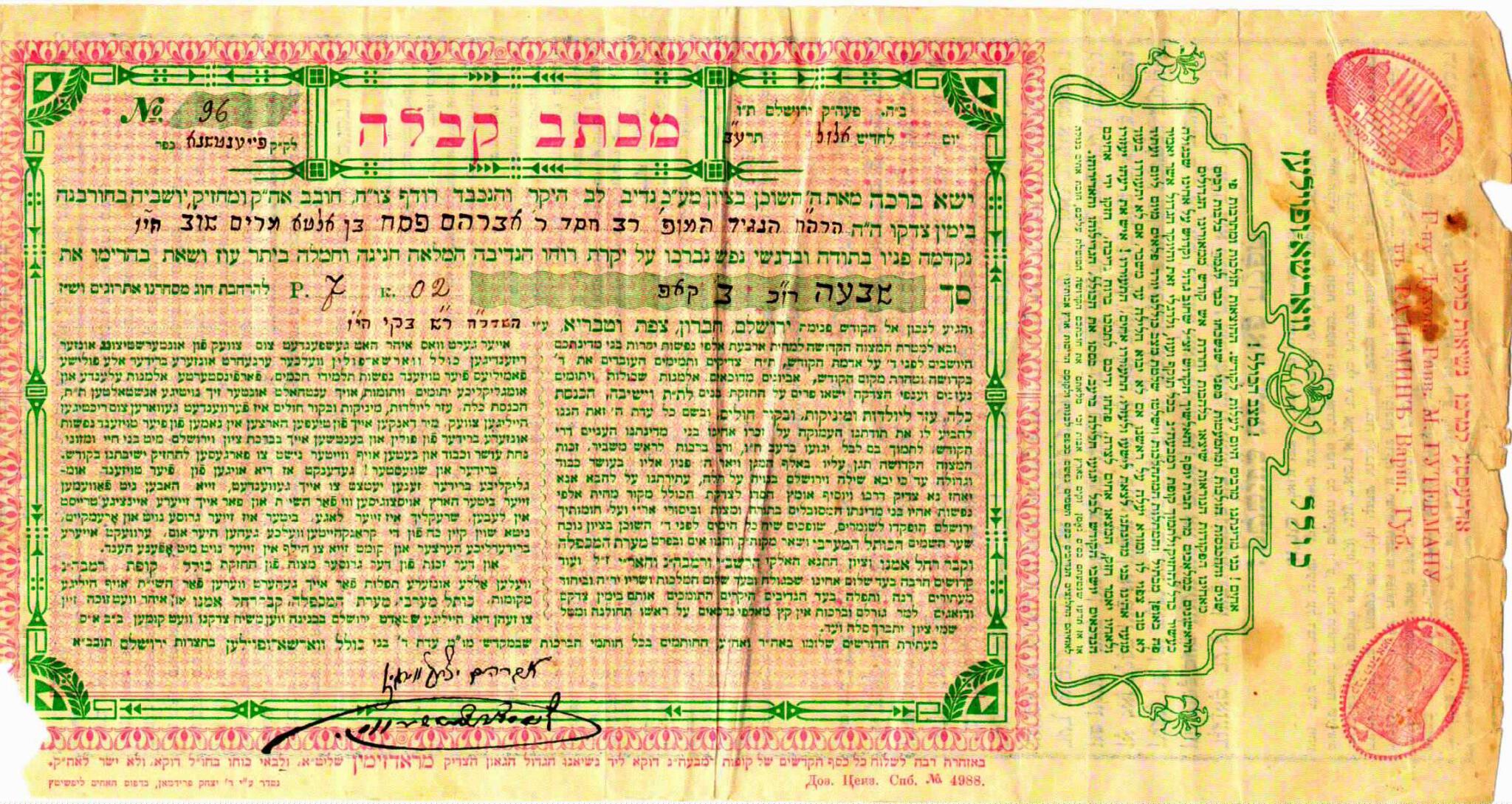

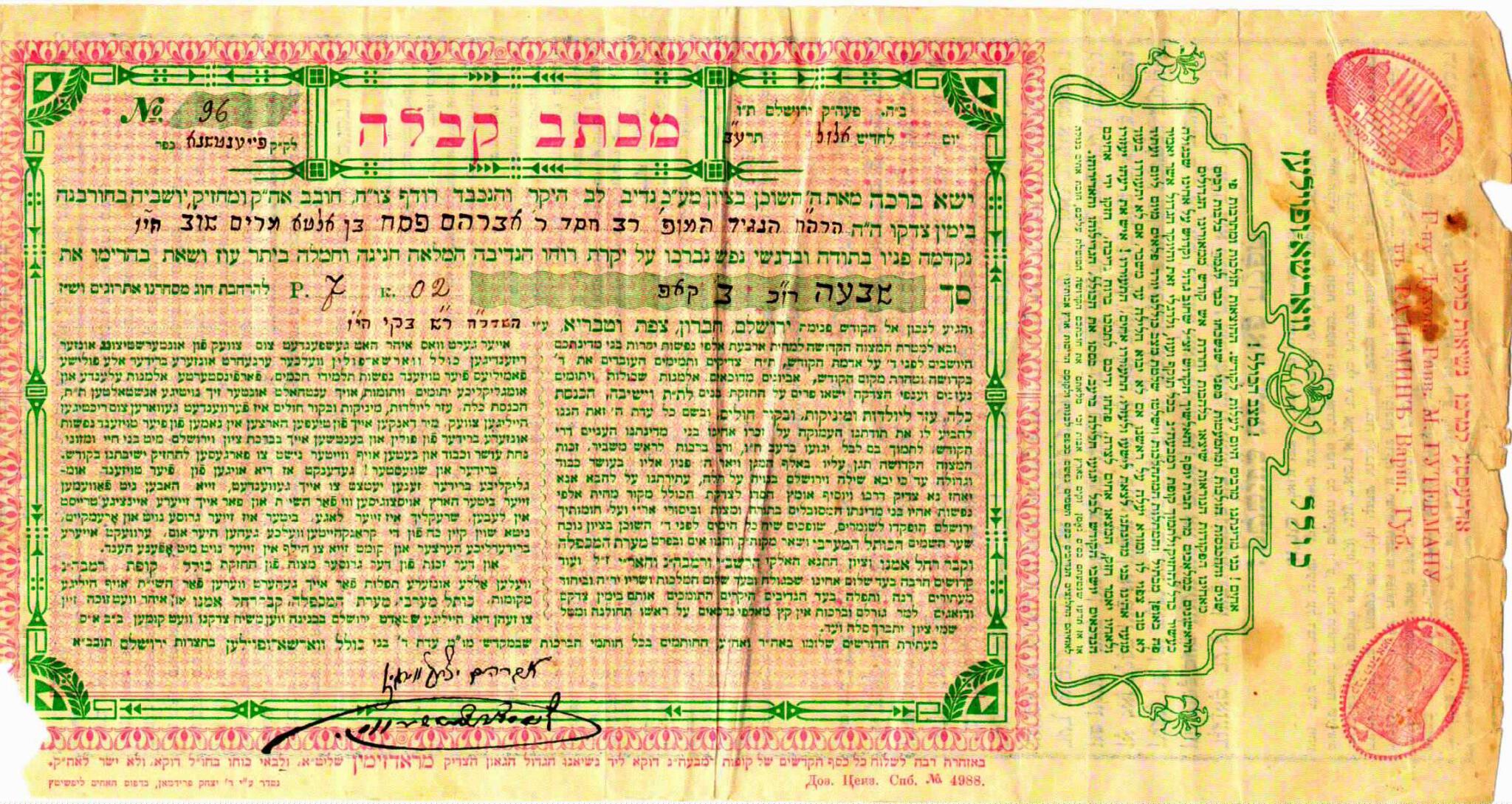

A receipt for a donation of seven rubles from a Kollel (yeshiva for adult males) in Poland to the Jews of Israel

The Gemara of a Young Girl

The Gemara of a Young Girl

The Nazis didn't stop at only taking young men; before long they were rounding up all the Jews. My mother's family was taken to the ghetto of Pabianitz. Each person was permitted to take a suitcase containing whatever was necessary for the family. A suitcase! For a family of fourteen people, and a houseful of posessions. How do you pack up your life into one suitcase? WHat do you leave behind, and for how long would they have to live out of a suitcase?

Mama was thirteen years old, but she and her younger brother were the "little ones" of the family. The older ones always knew better what should be done and how, so Mama and her little brother stood aside, looking on as chaos spread through the house and panic appeared in the eyes of the elders.

Her mother was beside herself. So many people were depending on her! She flitted among the kitchen cupboards and drawers, feverishly scanning their contents and desperately wondering which items to take. Time was running out, and the suitcase just wasn't big enough. She couldn't possibly fit in the china...and there was no point in taking the silver. Finally, she selected a potato masher, flourished it like a soldier claiming his plunder, and stuffed it into the suitcase.

To this day, the image of her mother holding up that pathetic potato masher is branded in Mama's memory, encapsulating the breakdown of the world she knew, a world where things made sense.

They were hustled out of the house as if it were an emergency, with no chance to pack up and store their things or to leave a letter. It was all unreal. A wonderful wlecome to the ghetto.

All that day, chaos prevailed. Suitcases and duffel bags, people, wagons, horses, and babies...all were shoved into the ghetto as if there weren't a moment to spare. The families were all looking for someplace where they could possibly live. But nothing was possible, nothing.

Little Nadja looked around her in dismay. The whole crowded space was pervaded with fear, so thick she could smell it. The one suitcase was full of an odd assortment of things, and nothing was as it should be. But worst of all was when father cried, "Oy! I forgot my Gemara!" and they all froze in shock. Tatte (father) had left his Gemara at home...and the curfew had already began. No one could go back to the house for it now. And that was the moment when all this pent-up pain and anguish spilled out to the surface.

His precious Gemara, his very life's blood, was lying there on the table in the big house, on the starched tablecloth, back there where they'd left normal life behind for this insanity.

How could this have happened? Nothing in the world was more important than the heilige (dear) Torah.

Mama didn't stop to consider. To her, there was no question, there was only Tatte's anguish, and the Torah he needed - that they all needed - like water to drink. This miserable, crowded space, maybe even more than the comfortable house, needed to be filled with the melody of Tatte's learning. Somehow, Mama knew that once the Gemara was here, it wouldn't be quite so dark. Some of the bright, familiar light of home would come back to them.

Silently, Mama got up, tiptoed over the mattresses that covered the floor, and felt around for her shoes. It was ten o'clock; she should be sleeping by now, but instead, she crept out of the house, slipping past the soldiers patrolling the streets until she found herself at the boundary of the ghetto. The wall hadn't been built yet. Rows of soldiers, armed with rifles, marched back and forth, blocking anyway from going in or out.

But somehow, Mama got out, not even knowing the magnitude of the risk she was taking. And then, light on her feet as a gazelle, she ran through the familiar streets toward home. With a trembling hand she opened the door, which hadn't been locked, and entered the house, breathless. The hosue caressed her senses with its lingering fragrances, the feel of the soft rugs under her feet, and it filled her with longing - but there was no time for that now. The Gemara lay on the table, closed and waiting. Mama picked it up, and holding it close to her heart, hurried back to the ghetto. Once again, she found a way to escape the soldiers' notice and sneak past them, unaware of how much she was risking.

Mama found the apartment where her family was housed and went inside, to her father, holding the Gemara before her like a flag of victory.

The family stared at her, stunned. What was this? "Nadja," her parents wanted to know, "where did you get that from? You went home?! How on earth..."

Her father took the Gemara and put it down. He hugged her with all the love in the world, and then gave it a light slap on the hand with all the love in the world.

Mama was a thin slip of a girl, who was always being urded to finish her milk or her kasha (buckwheat), so she would be strong and have some flesh on her bones. And she, of all the children, had sneaked out of the ghetto and back in again, past merciless, armed guards! "It was wrong of you to endanger yourself like that," her father reprimanded her, with nothing but concern in his eyes. "The Gemara isn't more important than your life. Don't ever go out again without asking our permission..."

Mama stood there, silently accepting her parents' rebuke, her lovely blue eyes fixed on the floor. She didn't know hwo to explain it to them. But she knew inside that she couldn't have done differently. She simply had to go and get that Gemara.

That night, the singsong melody of her father's learning filled the house once more, carrying away their pain and sorror, their fear and confusion on the soaring notes of "Zogt di heilige Gemara..." (This is the dear Gemara). Their anxious breathing slowed down, and they deeply inhaled the words, the song of life that had followed them even here. And Mama knew that although she'd risked her life, she had brought her Tatte a gift of life.

(How Could I Not Have Known, Chana Rotenberg)