The holiday of Passover occupies a place of honor in the Jewish calendar, being the holiday that symbolizes our exit from slavery to redemption and our becoming a nation. Even during the Holocaust, Jews did not give up observing the mitzvah of Passover, and this raised difficult and heavy questions: Is it possible to avoid eating chametz (leaven) for a week, when all the food one had was a slice of moldy bread? How can one drink four glasses of wine when even water is a precious commodity? And is it even possible to celebrate a holiday whose essence is freedom and royalty under the burden of Nazi enslavement? In the persistent attempt of the Jews to keep the mitzvot of the holiday, it was not only the “four questions” (of the Passover Hagada) that arose, but a barrage of difficult and complicated questions – and who would be the father to answer them?

Teaching Kit – Freedom within Slavery

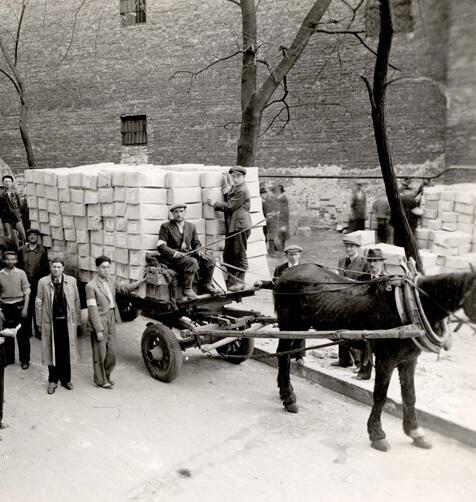

Judenrat members moving Matzah to be distributed in the Warsaw Ghetto, Poland

Hard Labour in the Melk Concentration Camp

Hard Labour in the Melk Concentration Camp

The week before Passover, I began to think about how I would succeed in not eating, G-d forbid, chametz (leaven) on the holiday. It had been three years that I'd spent Passover in concentration camps, and thank G-d, I had been successful until then, and chametz did not pass my lips on those Passovers. I planned for this Passover not to be different from its predecessors…

I learned that one of the workers in the kitchen used to live in Radom. I immediately turned to him with a request that he give me potatoes boiled in their skins on the days of Passover, in exchange for giving him a portion of my daily ration, bread and meat. He accepted the proposal, and I made my way to my bunk happy and good-natured.

On the eve of Passover at 11 in the morning, a doctor's check was held at the hospital. The patients whose condition allowed them to go entered the room, where the Jewish doctor sat along with the German doctor, who was the commander of the hospital. The doctors approached the weak who could not get out of their beds, and they decided what to do with each patient: whether he was permitted to stay and be treated in the hospital or be sent to death.

I entered the doctors' room and showed them my leg. There was a huge ugly scar over the wound that had been on my leg for a long time. The doctors took a look and both said in unison, "You are as healthy as any other person - to work"! The "healthy legs" (?!) almost carried me in a dance, comparable to the "Exodus from Egypt" on the eve of Passover. I did not believe that I would be allowed to leave the hospital and here I was walking out of it "healthy and safe".

Chametz instead of matzah

I joined the work group hungry. This was work in "Stollen", the work of cutting the giant tunnels in the bowels of the earth, in the Tyrolean mountains. It was hard, arduous work, in which the workers were replaced within a short amount of time, sturdy and tall people turned into human skeletons and after a short period of time fell, lifeless… May G-d avenge their blood! I joined the employees at "Stollen". I got an electric air hammer with the help of which I started carving in the mountain. Dirt and soot filled the area and I lacked oxygen. I felt myself collapsing into myself.

Black circles floated before my eyes as I returned to the camp exhausted and tired, unable to stand on my feet. With the rest of my strength, I inquired about the food we would receive, would it be a stew, or would it be bread, after all, the first day of Passover is today… My friends answered me that sometimes they get cooked food, and sometimes bread. I was hoping that this time it would be cooked food, and not actual chametz - bread. But it was no so, the nimble among the prisoners carried in their hands thin slices of bread, which they had just shared…Feelings of loss and failure filled my dying heart, I felt my mind emptying, my strength running out. My hands fell limply to my sides, my eyes filled with tears and my heart fell. But this morning I was happy about the arrangement I was able to reach with the kitchen worker. I had promised that I would be able to get through this Passover as well, without chametz entering my mouth, and here bread was being served. This was the first time for me during the war years, in which I spent in the concentration camps, that I was being forced to eat chametz on the first night of the holiday…

The hourglass was quickly running out. I felt that I was closer than ever to death… The slice of bread was placed in my mouth and a fierce war raged within me: On the one hand, my weak body threatened to devour the slice and swallow it in an instant. On the other hand, my heart was driven, and it harassed, poked at me and didn't let up - would it be possible, to eat chametz on Passover? I went to the corner, I prayed tearfully, by heart, alone. I had no prayer partners, and when the tears washed through my eyes, without stopping. I could not stop. I continued my prayer and whispered in pain, Master of the universe, let it be so… for it is written "and live by them" (the commandments)… I continued to cry, I cried without respite. After all, we eat the arm of a chicken in memory of the "celebration", charoset in memory of the "mortar", and karpas (celery, parsley or another vegetable, depending on the family's custim) in memory of the hard work in Egypt. And now, it has been reversed: we work hard on the Seder night and kneel under the mortar, the material and the bricks, and eat bread instead of matzah. I forced myself to eat the whole slice, its crumbs sticking in my stomach like swords. I continued my reflections; our fate here is similar to the fate of our ancestors in Egypt. We also had to work in hard labor, with material and bricks, on the one hand, and on the other hand, our neighbors abuse us cruelly! Our land had been conquered and bitterness was abundant. We too, like in the Egyptian exilees, eagerly awaited the redemption, the day when we will go from slavery to freedom, from captivity to redemption from days of mourning to holidays and from death to life…

The next day I managed to arrange food for myself for Passover.

The Candles That Were Not Extinguished - Mordechai Deutscher - Published by Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

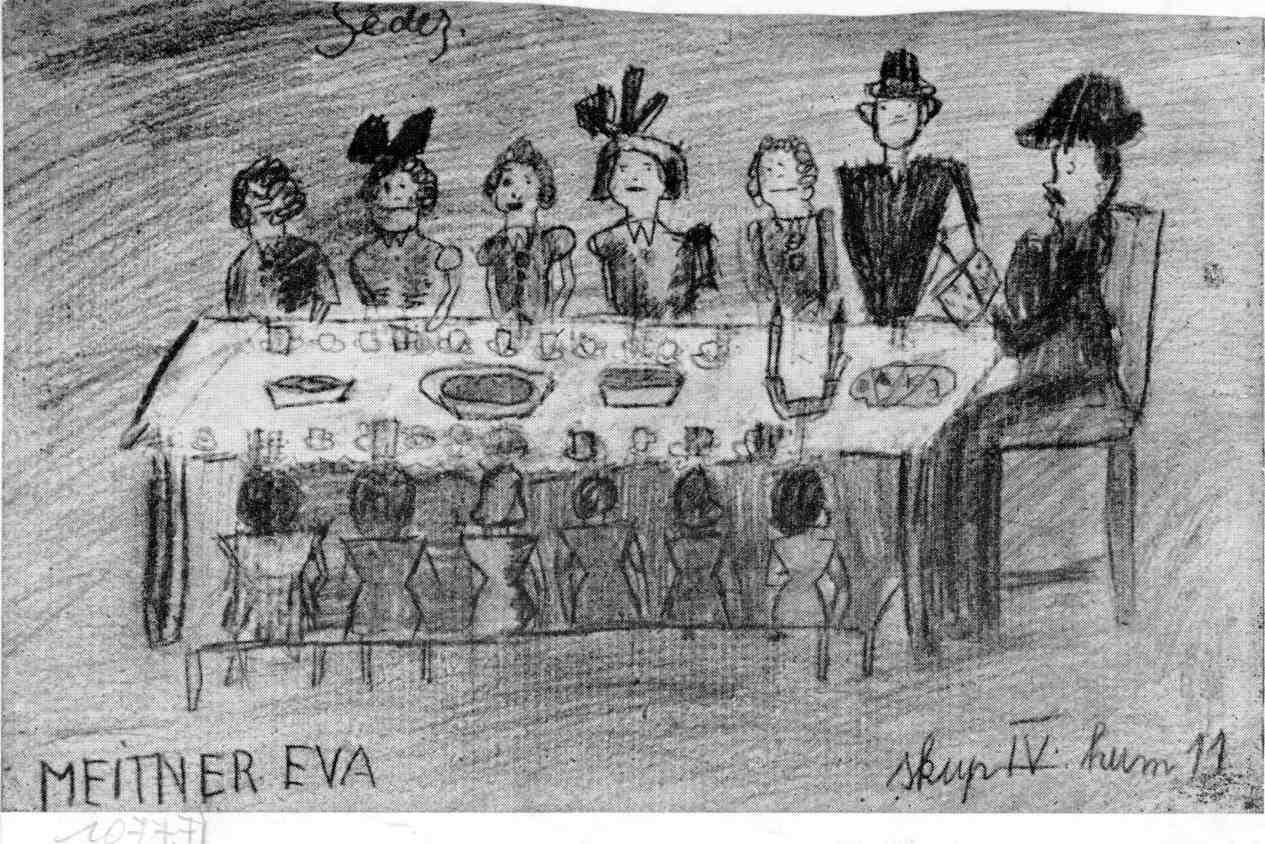

Drawing of a Passover seder table by Eva Meitner, a child in the Theresienstadt Ghetto

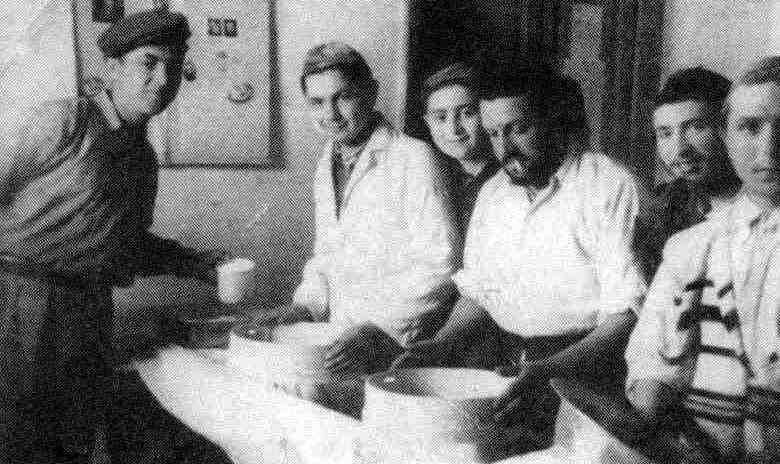

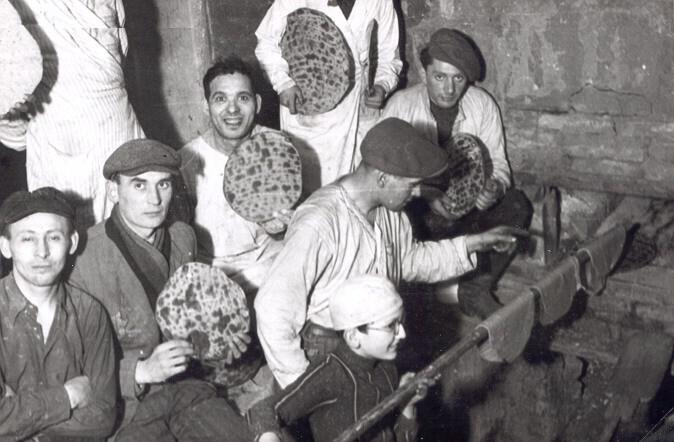

Surviving young men bake matzah in the Santa Cesarea DP camp in Italy, under the guidance of Rabbi Leibel Kutner

Self-Sacrifice in the Valley of Death - Baking Matzah in the Bergen-Belsen Camp

Self-Sacrifice in the Valley of Death - Baking Matzah in the Bergen-Belsen Camp

A special chapter in the stories of self-sacrifice of the Bluzhever Rebbe, Rabbi Yisrael Spira.

When Passover 5704 (1944) approached, a group of 70 Jews in Bergen-Belsen organized themselves and gave a signed request to the camp management, asking to receive a small amount of flour each day instead of the daily bread distributed among the prisoners. Their goal was to be able to bake a few matzahs every day for Passover. The rabbi who was the spirit of life in the group of people who constantly ensured the existence of a "kosher kitchen" in the camp for religious prisoners, was chosen as the representative of the group to deliver the letter of request to the camp commander.

The commandant accepted it with an amused mocking gesture, but a moment later he replied that he would forward the request to Berlin and would deal with it according to the instructions he would receive from them.

When days passed without a response, the members of the group were filled with the fears that they may have harm themselves with their "brazen" wish, and who knows what was in store for them. But two or three days before the holiday, two SS officers accompanied by fearsome dogs suddenly arrived to where the Rebbe was housed and immediately ordered him to report to the camp commander. The Rebbe prepared for the worst and asked the people around him to remember his yarzheit (anniversary of death) day. It was close to Passover, and with the confessional prayer (said before death) on his lips, he went to the commanding officer's office trembling. How great was his surprise, when they announced the news that he would receive from Berlin permission to give flour to the group's members - a special privilege for foreign nationals - to allow them to bake matzah. According to his order, workers were even told to make a small brick oven in one of the barracks in the area of the camp where foreign nationals were housed. The group members' joy grew beyond measure. They began to bake a small amount of kosher matzah.

But all of their joy was interrupted, when one day the commander of the camp suddenly appeared, boiling with rage, and with a strong kick of his feet, shattered the small stove into pieces. What happened? It turned out that someone tried - and failed - to smuggle a letter out to nearby Switzerland, in which he described the suffering of the Jews in the camp. The letter fell into the hands of the Germans, and the commander in his anger severely reprimanded the Rebbe and scolded him: "I behaved so nicely towards you, I even allowed you to bake matzah, and you dare to spread 'lies' and slander us to the wider world - is that how it is done? Is this your way of expression gratefulness?" The Rebbe apologized and promised that he had no knowledge of this, but the commander did not give up: "You are the rabbi of the Jews… I put all the responsibility on you… within the next few hours you must find out who wrote this and turn him in…" The Rebbe responded to the German's words with determination: "I have already explained that I have no idea who did this. However, even if I did not know the man, I would not reveal his identity to you, sir. I am not ready to do so, I will not save myself by sending someone else to death - if you wish, you can shoot me right now!" May G-d have mercy. Hearing his decisive voice, the commander retreated for some reason and returned his drawn gun to its holster. A tone of disappointment rose from his mouth as he muttered, as if to himself: "If only all the Jews were like Rabbi Spira, many things would not have happened in this war…" and with a characteristic raised hand hinted that the Rebbe was freed.

Ma Nishtana HaLila HaZeh? (How is this night different? - The 4 Questions)

When Passover began, the Rebbe held the "seder" in a secluded corner, without a shulchan orech (the meal part of the seder) and without leaning (a custom to show the comfort of being free), but sitting on the ground. Along with him were a small number of children and adults. Amonsgt them as well were the Bluzhover Rebbe and his brother Rabbi Yitzchak Elazar. They placed in front of the Rebbe some matzah, a potato, and a beet, inside the remains of a broken vessel that served as the seder plate. A zeroa, charoset, and the egg (all three are symbolic inclusions on the seder plate) were nowhere to be found. They had more than enough marror (bitter herbs)… In every situation they were in, a a verge large amount of marror was present.

With special enthusiasm, the Rebbe told the children about the exodus from Egypt. One of them asked the 4 Questions - Ma Nishtana. The eyes of those present welled up when the boy in his young sweet voice repeated the age-old questions that Jews all over the world have been repeating for thousands of years.

When the boy finished saying the Ma Nishtana, the Rebbe repeated the questions and gave them a different interpretation than the usual, He began by saying: "Why is this night different from all other nights?", and after all, the dark exile is referred to as a night, why is this exile so much worse than all the other exiles the Jews have experienced?! "That every night we eat chametz and matzah, but this night we only eat matzah" - the chametz swells and rises, the matzah is shallow and low. Why in every exile have we had high and low times, but this time we are in a completely low situation. Never have the Jews been in such a low place as they are now?! Why tonight - is this exile so bitter?! "And we are all leaning," lying on the ground, unable to get up. Why?!

Here the Rebbe lifted his eyes to the Heavens and continued: "Know, children, that every night before dawn, the darkness increases. We are very close to the complete redemption and that is why our eyes have seen so much darkness. This is implied by the author of the Hagadah. "Avadim Hayinu..." (We Were Slaves) stands for "David ben (son of) Yishai, your servant, your messiah" to imply that this is the reason for the difficulty of our exile, the righteous messiah is about to come soon and redeem us.

With these words, the Rebbe strengthened the spirit of the tortured Jews who gathered around him that night, among them desolate children who had never tasted sin, in the concentration camp on the Land of Blood.

Ephraim Manela – Matzah for Passover in the Ghetto (Sosnowiec, Poland)

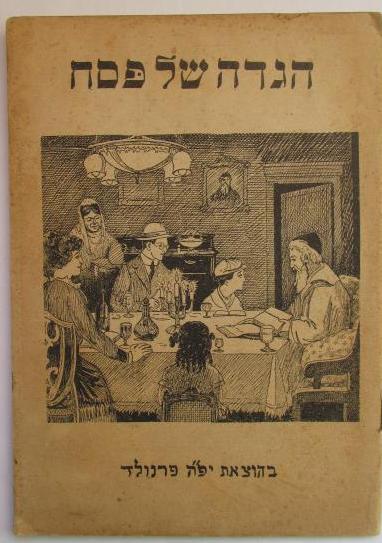

Cover page of a hagada from the Foerenwald DP camp, Germany

Boiling vessels (to make them Kosher for Passover) in Lodz

Next Year in Jerusalem - In Bergen-Belsen

Next Year in Jerusalem - In Bergen-Belsen

The first days of spring had come, hearlding the approach of Passover, the joyous festival of freedom and redemption. Would anyone be left in Bergen-Belsen to celebrate, or survive to witness his own redemption?

Our Zehnerschaft (group of ten), like the rest of the camp, was separated by the epidemic. Some had returned from the infirmary, still sick, dragging their swollen feet. A few more were still hallucinating in the infirmary. The rest were waiting their turn.

Even in this condition, it was a double blessing to go to work: for the sense it gave us that we still existed...and for the turnips.

"What now?" Rivkah asked one day. "It's almost Pesach, and we have no matzas." I had already comtacted the men in the Internierunglager (prison camp area for foreign citizens), who had a better chance than we did of baking matza. They had promised to help, but thus far nothing has been forthcoming. All I wanted was one matza for us to say the blessing over. I searched for other ways.

"I asked Naomi," one girl reported, "but she can't lay her hands on any flour in the kitchen."

"I asked Hanka if she could dig out something from the stockroom," Rivkah added. "She can't. The only way is through the men in the Internierunglager."

Nothing happened for the next few days. We had no matzas, no wine, no kneidlach. Only one thing was plentiful: maror - bitterness, misery, sickness, death, pain, cruelty. Scores of thousands would greet Passover in Bergen-Belsen this year: some sick and some dying, but most of them piled stiff and white all over the camp.

Even so, the peeling-room crew sat down for Seder on the first night of Passover. There were two Rivkahs, Ruchka, Rega, and several other Bais Yaakov girls in the reduced crowd. Rivkab Englard said Kiddush over some ersatz coffee saved from the morning ration. Then came the Hagada. Someone started from memory; someone else continued. Everyone contributed what she remembered. As for the parts we did nto remember, our present circumstances filled them in.

I had prepared three "matzas" - white, thin, almost round. As I covered them with a square rag, the assemblage waited for the surprise I had promised. "Here are the matzas," I announced, uncovering three thin slices of turnip. They looked like matzas - almost.

"What kind of matzas are those?" the girls asked, laughing. I was quite serious. "And what kind of a Seder is this? Those are the matzas I was able to make: the rest is up to Hashem.

"Don't you remember the story of Rabbi Chanina ben Dosa?" I continued. "One erev (eve of) Shabbos, his daughter ran to him, crying, 'I poured vinegar into the candlesticks instead of oil. How will they burn this Shabbos?' Rabbi Chanina put her at ease: 'Don't cry, my child' He Who told oil to burn can tell vinegar to burn.' Miraculously, the candles shone brightly all that Shabbos, and were even used to light the Havdalah candle."

"Wouldn't it be easy for He Who turns dough into matzas to turn turnips into matzas?" I asked seriously, waiting for a miracle to happen. It did not. The embarassed white turnip did not turn into a crisp matza. So at that night's Seder, we did not say the blessing over matza. But we did over the Karpas (the sweet turnip) and the maror (bitter herbs). Of maror there was plenty: around us, between us, inside us.

"If I live through this Gehinnom, Rega declared fervently, "the most important food on my Seder table will forever be a turnip." This was the cue for nostalgia for Seders gone by, with everyone exchanging stories.

Later came Hallel (a prayer), and, finally, "Chad Gadya" - the story of a lamb that Father bought for two zuzim. The world wanted to destroy the little lamb, but each time devoured itself instead, until the Final Judgement came. G-d Himself descended to earth to judge the generations that would not let the innocent lamb live in piece - the lamb that He had bought for two zuzim to bring light, justice, and joy to the world.

We finished with song and prayer "Next year in Jerusalem," a song of hope against hope, a tiny spark of life in the Valley of Death.

To Vanquish the Dragon - Pearl Benisch

Yosef Ansbacher – Beets for the Four Cups of Wine (Brussels, Belgium)

A hagada printed for Holocaust refugees who were sent to Cyprus

Selling My Chametz

Selling My Chametz

My uncle, my mother's brother, lived at 34 Dav Otsu Street before the war. "Let's go there." "Maybe they are still alive and they will be able to host us and help us," I said to my friend Magda Singer who accompanied me. We walked the streets of Budapest, every second house was destroyed by the Allied or Russian bombings. Everywhere there was barbed wire and piles of dirt and debris, the roads were destroyed and the sidewalks were broken, but amazingly the house at 34 Dav Otsu stood intact, unharmed.

I stood in the street, looked at the house and hesitated for a moment before I went up and knocked on the door, afraid of disappointment… I finally gave in. I went up the stairs with Magda as we held onto each other with hope… maybe we won't be disappointed… we knocked on the door which miraculously was opened for us by my uncle Miksho Batchi himself.

"Chani!" He recognized me despite my skinniness and my hair that had only just started to grow back. "Piri!" he cried to his wife excitedly, "come see what guests just arrived!"

Piri Neini received me with a warm hug and with tears of exciement mixed with tears fo sorrow, because with my arrival they received the news of the death of those who did not return with us.

My friend Magda went on her way with the group who wandered along with us to Budapest. I remained in the house on Dav Otsu until after Passover.

Before the holiday, I went to the offices of the Joint. I worked with a woman named Sidi Feldman. She got me new clothing and shoes. She also got us matza for Passover.

I had a loaf of bread as dry as an old tree, which I carried with me along my wandering path home.

The loaf was so dry and shriveled, but it was still bread, and to me it was of great value. These were times when there was no certainty of anything. Deep in my heart I did not believe that the nightmare was over, I was not sure that the terrible war was behind us, I was not protected from the fear that the Germans would return to rule over us. Inside I was afraid that one day the hunger, deportations, and wanderings would return again. I wasn't ready to part with my loaf of bread - it was a kind of "insurance certificate", a "mouthful of bread" in the simplest sense of the phrase.

But Passover was approaching, and Piri Neini explained to me that according to halacha (Jewish law) there is no permit that would allow me to have the square of bread in my possession during the holiday. With no choice, and with a heavy heart, I went out into the street and… believe it or not, managed to sell the old, dry loaf of bread, which was which was barely fit for human consumption to one of the gentiles for a few pengos.

The Apple Tree - The Story of Chana Galandauer, Holocaust Survivor

Preparing matzah in a bakery in the Lodz Ghetto

Rabbi David Brudman – “Ma Nishtana” (The Four Questions) in Theresienstadt (The Hague, Holland)

Avraham Abba Factor – The Hagadda and the Book of Esther (Enschede, Holland)

Yehudit Rubinfeld – Leaves with a Special Taste/Passover in the Camp (Lutynia, Hungary)

What I Learned at My Father's Home

What I Learned at My Father's Home

In Bergen-Belsen, Bronia's dedication to the education of her two small sons, Zvi (later the Bluzhever Rebbe) and Yitzhak, was viewed by some as an obsession bordering on insanity. She would deny herself food, bartering for her children's education. For a piece of bread and a potato, Mr. Rappaport taught her children Jewish law and tradition. She hersefl taught the children the weekly portion of the Five Books of Moses. At times, the children were so hungry that they could neither hear nor see. Words became muffled, distant sounds and the letters seemed like a colony of busy ants rushing in all directions.

When Passover approached, Bronia's program became more rigid. She insisted that the children learn all the laws and customs pertinent to the holiday, while she herself supervised their studies and hustled some beets and potatoes, and these she saved for the holiday so she and the children would be able to manage without bread.

Bronia did not rest until she got rid of her chametz, or leaved food and bread, as required by tradition. She sold it for the duration of the Passover to a gentile woman from Prague, the wife of a famous Jewish lawyer. Both of them were now inmates in Bergen-Belsen. Bronia's sale of chametz became a source of mockery, and people taunted her and asked if the sale of chametz were her only concern at this particular time and place.

"I learned the Jewish tradition in my father's home when I was a child. Now it is my duty as a Jewish mother to teach it to my children in my home."

"Some home, a Nazi concentration camp!" someone said, while glancing at the two children with pity for their sad lot, being children to a mother who had lost her mind in these troubled times.

One their way back to theri barracks, Bronia and the children stopped at the infirmary. A long line of people were standing and waiting for treatment that would offer relief from their pain and discomfort. Two German doctors in white coats passed by on their way to the infirmary. One casuallly pointed to the people on line and said to his companion, "I don't know why G-d has punished me so severely by forcing me to witness daily such ugliness as these Jews."

Bronia glanced at the line. All around her were skeletons disfigured by disease and starvation, covered with boils, blotches, and sores.

"Mutti (Mommy), did you hear what the German doctor said?" asked Zvi of his mother.

"Yes, I heard," Bronia responded. "Just study and be good, for a time will come when we will once more be a great and wise nation. Remember the Ten Plagues that G-d brought upon Egypt?"

Zvi was comforted. In his mind he saw Germans cobered with sores, boils, and lice, while the Jews were marching to freedom through the open gates of Bergen-Belsen.

Passover came and went, and the Jews of Bergen-Belsen were still slaves behind barbed wire. One the evening when Passover ended, a woman by the name of Mindel Heller came running. "Bronia, it is a matter of life and death. The Rabbi of Pruchnik is almost dead. He hardly ate during the Passover holiday, and now he refuses to eat chametz that was not sold priot to the holiday as required by law. i heard that you are the only person in camp who sold your chametz."

Bronia did not hesitate for a moment. She took out a loaf of white bread, her most precious posession, and gave it for the Rabbi of Pruchnik.

People around her nodded their heads in disbelief. "Woe to a woman who gives away her children's last bit to a stranger," said people in her barracks.

"What I learned and saw at my father's home, I want my children to see and learn in my home. I could not choose the home but I can preserve its spirit." said Bronia as she handed the bread to Mindel.

"Mutti, Passover is over and we are still slaves and the Germans eat pleanty and are free and clean," said Zvi as Mindel Heller was rushing with the bread to the Rabbi of Pruchnik.

"My child, the Jews were slaves in Egupt for 210 years and then freed. We have been slaves for only the past four years," said Bronia. Little Yitzhak, who was listening to his big brother's questions, said "The Ten Plagues are here, so the Exodus to Freedom will soon follow,"

Zvi was tempted to point out to his younger brother that at present it was the Jews who were afflicted with the Ten Plagues and not the Germans, but he remained silent.

"Where are we going to be next year on Passover?" Zvi continued to ask. "In Jerusalem," responded Bronia.

"How do you know?" Zvi continued to question.

"I learned it at my father's home," said Bronia.

Mindel Heller returned. The Rabbi of Pruchnik was improved. Bronia's bread had saved his life.

When Rebbetzin Spira (Bronia) finished her story, she said to me, "Do you know the value of the loaf of bread I gave Mindel Heller?"

I shook my head.

"Today a skyscraper on Times Square is less valuable than a loaf of white bread was in Bergen-Belsen," said Bronia Spira.

Based on a conversation between Rebbetzin Bronia Spira with Dina Spira, May 2, 1976, and a conversation between Prof. Yaffa Eliach and the rebbetzin on April 26th, 1979. Taken from the book "Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust," by Yaffa Eliach, pages 123-125.

An American Jewish soldier gives matzah to a child in a DP camp in Germany

Baking Matza and the Seder Night in a Concentration Camp

Baking Matza and the Seder Night in a Concentration Camp

A hard winter came upon us in the year 5705 (1945) in the Vaihingen concentration camp in Germany. We faced hard work in the stone quarries, night shifts, cold and hunger, and as well, the typhus epidemic prevailed in the camp, which claimed many lives. On top of these were the victims from the brutal murders of the SS. The result was fainting and indifference to everything that was happening. However, even in this camp there were individuals who stubbornly maintained their Jewishness until the last moment. Passover was approaching, and these people thought of the question, how can one avoid eating chametz?

A few days before Passover, one of the SS men entered the workshop where I was working making signs, and asked me if I could make shooting targets for him. At that moment, a thought flashed in my mind and I offered him to make large targets on which pictures of shooting soldiers were pasted. For this, I told him, I need a large quantity of flour, for the purpose of preparing the glue.

The German liked my proposal and so he gave me a note for the food warehouse to receive 5 kilograms of flour. Seeing the time of salvation, I immediately went to the kitchen manager and told him about the matter. Hela, a Czech of German origin, was very interested in the program, I mustered up the courage to add a request: to give me 10 kilograms of flour. To my surprise, the majority agreed to my request, on the condition that I would not take out the flour all at once, but in small quantities. I couldn't believe what I heard, but it was true, and I now had a permit for 10 kilograms of flour.

After transferring the flour to the workshop, I called my friends and revealed the miracle to them, and their joy cannot be described. The extinguished will to live was rekindled. We "organized" some wood, found a wheel and started the holy work, after we scrubbed a table with the help of glasses, and put some hot bricks on it.

The workshop bordered the camp elder's room. After the wall warmed up, he suddenly knocked on the door and demanded that we immediately open it. Having no choice, we opened it, but after he saw the unleavened bread and our work, he stopped in great surprise, and only asked us to continue quietly, lest we attract the attention of the patrol guards. When he left the room, he asked that we not forget about him and leave him a portion of matza on the first Seder night.

With the speed of a lightening, the news spread amongst all the Jews in the camp, and hearts began to beat again with hope, at the sound of the success of the daring action.

On the first Seder night, we gathered in the workshop as in the days of the sceret Jews in Spain, and reverently we opened by saying: "We were slaves…" We were each given three matzas, and instead of wine, we used water sweetened with sugar. We had potatoes for "karpas" (the symbolic vegetable) and white beets for "maror" (bitter herbs). There was no shortage of salt water…

We recited the Haggadah from several prayer books that we managed to hide the whole time. After we finished half of the Hagada, Azriel became enthusiastic and began to demand from us not to despair, to withstand the test of suffering, for redemption was already near… After that we learned that others were standing outside on guard. Indeed it was a "guarded" night!

Moshe Perl, The Book of Radom (Translated from Yiddish), Tel Aviv, 1961, in Mordechai Eliav (editor) I Believe: Testimonies on the Life and Death of People of Faith during the Holocaust, Jerusalem 5739/1978, page 219.

Dov Osdorf and Yehuda Van Dyke – Passover in Hiding (Rotterdam, Holland)

Abba Halperin – Words of Encouragement from the Klausenberger Rebbe (Lithuania – Israel)

Shlomo Abrams and Yona Emanuel – Passover in the Bergen-Belsen Camp (Holland)

Ha Lachma Anya (This is the Bread of our Afflication) in Auschwitz

Ha Lachma Anya (This is the Bread of our Afflication) in Auschwitz

In the 2 or 3 days before Passover 5703 (1943), one could notice a special expression of anguish and sorrow on the faces of the charedi (ultra-Orthodox) Jews in Auschwitz. Neither the gas chambers, nor the daily selections, nor the brutal forced labor, nor even the tormenting hunger and death of the victims left their mark on them at that time. What made them so upset was the torturous thought of having to eat chametz on Passover. Their sorrow was too much to bear, and more than once one could hear a heartbreaking sigh from these Jews. When one of them was asked what he was sighing for, he replied: "Yes brother, in a few days Passover will be near, and it will be the first time in my life that I have to eat chametz." The sighs keep multiplying. You could also hear things like, "After all, the holiday will last for eight days, and you can't fast that long."

Finally, the sad days of Passover of the year 5703 (1943) arrived in Auschwitz. In the evening one could notice complete depression in the barracks of the Torah-observant Jews, like the atmosphere of the Neila service on Yom Kippur. After a while, a number of Jews gathered in one of the corners of the barracks, and started reciting the Ma'ariv prayer to the tune use on holidays. After the prayer, when the crowd had dispersed, the voice of one of them, a thin and tall man, was heard: "Jews, don't forget that today is Passover - we have to hold the seder." From a remote corner of the hut, a trembling voice was heard beginning with the words: "Ha Lachma Anya." Suddenly, the people began to flow like shadows towards that corner. Between the narrow bunks, next to a broken and wobbly table sat a thin and gaunt Jew, and holding a small slice of bread in his hand, he called out in the tume used to read the Book of Lamentations: "Ha Lachma Anya…", and when he reached the words "Next year free men" and for the blessing of "Shehechiyanu," many burst into tears. Streams of tears flowed from desperate eyes. Did anyone else believe that they would ever again be free men, totally free people?!

The Jew holding the slice of bread continued to recite the Hagada in his broken and depressed voice, and when he reached the blessing on one of the four cups, he added his "promise" to the words of the "Hineni Muchan" (I am ready) prayer: Lord of the world, I promise you, that the blessing of the "creator of the fruit of the vine" I will bless in a year... And so he continued with the words of the Hagada, when the slice of bread in his hand literally symbolized the bread of poverty; He recited the blessed for eating matzah and marror (bitter herbs) and even came to afikomen (the part of the seder where matza is eaten as dessert), and every time he blessed, he took a bite from the slice of bread in his hand.

And then he arrived at the blessing "Shfoch Chametcha" (Pour out Your Wrath on Your Enemies). This wonderful Jew rose up and cried out: "Jews, I am telling you, perhaps this is an "et ratzon" (a goo time to request things of G-d), and we must pray and ask that a swift destruction will come upon our haters", and with a tearful voice full of sorrow we repeated after him as an echo: "Pour out your wrath…"

Zlatow M., Morgen Zhurnal (07/04/1947)' in: Eliav Mordechai (editor), I Believe: Testimonies from the Life and Death of People of Faith in the Holocaust, Jerusalem 5738/1978, page 224.

Rabbi Sinai Adler – Passover in the Mauthausen Camp (Prague, Czechoslovakia)

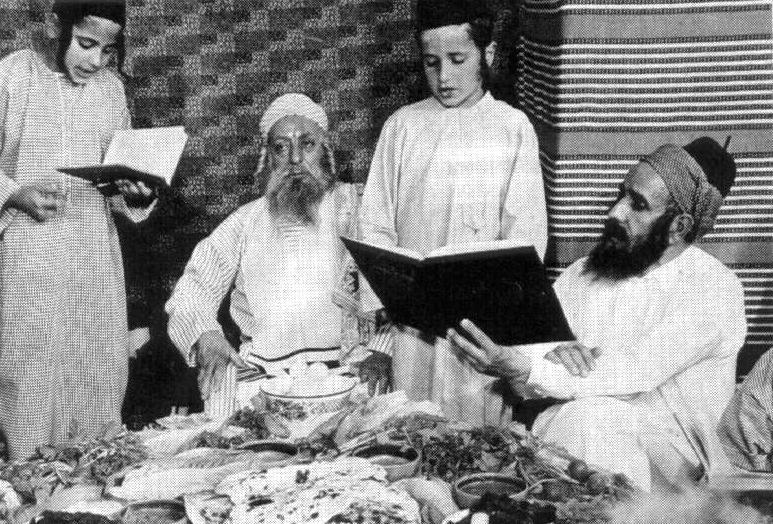

A Yemenite style Passover seder

Carmella Wertzel – The Last Passover (Szilagysomlyo, Transylvania)

Chad Gadya in the Middle of Auschwitz

Chad Gadya in the Middle of Auschwitz

As you can see, I am a regular taxi driver in Bnei Brak, I have the rare pedigree of being one of the most senior prisoners of the Auschwitz death camp.

I was on one of the first deportations sent straight from Slovakia to a work company, chosen after the strict selections in the death trains. I was about eighteen years old then, when I was expelled from my home town of Trnava. Along with me, several dozen other Jewish boys shared this fate. They were seen by the SS officers as fit for cruel exploitation in hard labor until they met their deaths. And my luck enabled me to withstand all the antics and abuses of Auschwitz, even though I was destined to live together with the angel of death for almost three years.

I was a young man, and when I fell into this bottomless pit I thought that the summer had ended for me in my young years. And here in "Block 14", where I was put together with about seventy healthy and lively young men, is where I recovered again. There were different boys among us, from respectable homes and poor families, poor boys and rich boys, intelligent as well as "simple ones". And the most important young man in our block - was whom? It was Itchi-Motel from the Mlawa Ghetto, which is in Poland. He was a chasidic boy whom we all liked and were ready to sacrifice ourselves for. He restored our human dignity, he rekindled the Jewish spirit in us. "Don't give up! Do not panic! Don't collapse in hell! Keep your will to live, despite the cursed oppressors, may their name be erased!"

What was Itchi-Motel's power? To be honest, to this day it is not entirely clear to me. It's not that I don't understand, it's just that we didn't have chasidic people in Slovakia, and I never heard chasidic music in my youth, like I heard in Auschwitz from the mouth of Itchi-Motel. I see him even now before my eyes. Skinny and ragged, because when he came to Auschwitz he was already fairly exhausted. He came from the ghetto after a long period of hunger and hardship. He was one of the "Seventy-four". By this, I mean that his tattoo number started with 74 thousand… and we, the boys from Slovakia, who came a long time before him to Auschwitz, were stronger than him, and we helped him. Itchi-Motel would sing his chasidic tunes to us. When he began to sing, we instantly forgot the furnaces and the kapos, and Auschwitz in general…

And how can I forget the Seder night that Itschi-Motel arranged for us. He kept track of the Jewish calender. I do not understand how he managed to do this. Everything was kept in his memory, everything was in his head. Each time it was Rosh Chodesh, whether it was one or two days. And every day of fasting. And it was the easiest thing for him, to fast and not taste anything. Well, his body got used to it. And it was possible for him to arrange the Seder night by "fasting", Itchi-Motel must have felt happy.

Our great question was when would we celebrate "the time of our freedom?" We had enough maror (bitter herbs), Matza - we did not even have an olive-sized portion, and we had the "four cups" but of tears, not wine...we didn't have anything to be ashamed of. We generally didn't cry in Auschwitz. Our hearts had enough and our eyes dried up. He who had a human heart - it was broken. The heart burst into itself and was destroyed. The exception was those who had faith burning in their hearts, these people endured, because they were stronger than the angel of death and the hell. And that's what Itchi-Motel was, and it brought us to tears. Not tears of fear and terror, God forbid. I am ready to swear that I did not feel any fear in Auschwitz. He who is already inside the furnace, surely has no more fear. And so it was with us, we lived right inside the furnaces. We clearly knew, if we don't burn today, then we will burn tomorrow. And what is the difference? Only Itchi-Motel drew from us tears of great excitement, tears of singing and exaltation, which is difficult for me to express, such tears we shed a lot on that first night of Passover.

When did we shed the tears? It was while Itchi-Motel sang the "Chad Gadya" song to us. Many songs were sang that night, what could we do? All the boys in our block slept on the wooden bunks, which in the prisoner language we called "shelves". We knew very well that the "Blockeltester" (block head) also knew the Jewish calendar, and he would ambush us on this night of "Osteren" (Passover in German). We chose to lie on our beds because in the meantime we had nothing to eat and nothing to taste in honor of Passover. Then Itchi-Motel began to sing special chasidic tunes in honor of the holiday. I don't remember everything. He sang "Vehi Sheamda l'Avotaynu v'Lanu" (And He who stood for our fathers and us) and he "Hodu La'Hashem Ki Tov" (Thank G-d for He is good) from the Hallel service, and he sang and sang some more. And all the tunes were like "impressions" of victory. Not songs of crying, only uplifting and encouraging songs. And because of that we were all overjoyed, and we shed tears like streams of water. But of all his tunes, he rose even higher when he sang "Chad Gadya" for us. Because then we all felt that we were overcoming and defeating the "kapos" and the "sondekommando", and the "blockeltester" and the corrupting devil himself.

Itschi-Motel sung "Chad Gadya" comfortably and joyfulling, as if he wanted us to understand the parable that lay in each and every word. Who is the "gadya" (baby goat) that "Father" bought? And what happened to him? And when he reached the end of the song, he raised his voice in a way that shook us all: "And You, G-d, slaughtered the slaughterer" - and again he repreated the phrase with emphasis: "And You, G-d, salughtered the slaughterer - and we trembled and were awakened because each of us understood exactly who the "slaughterer" was and that his end would be bitter and quick, at the hand of G-d, Himself.

Such was Itchi-Motel, and in this way, he breathed life into our dry bones. He himself lived through his chasidic tunes. After the Russians occupied parts of Poland and approached the camp, Itchi-Motel fell on the way, but until his last day he did not stop singing his chasidic tunes, and these tunes accompany me until today.

Yechezkeli (Prager) Moshe, Bais Yaakov: A Monthly Magazine on Matters of Education, Literature, and Thought, 59 (5724/1964), pages 6-7, Jerusalem.

Yitzchak Meir Shpernowitz – Passover Seder in the Siberian Steppe (Ostrow Ozowiec, Poland)

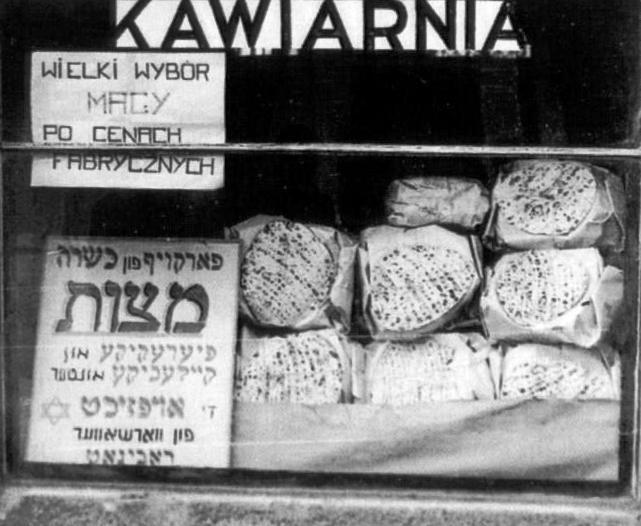

Matzah for sale in the Warsaw Ghetto

Seder Night in Bergen-Belsen

Seder Night in Bergen-Belsen

A few weeks before Passover, about 70 Jews in the section for foreign nationals in Bergen-Belsen organized into a group. Most of them were Hasidic Jews who had arrived at the camp from the Bochnia Ghetto. The majority of the people from the Bochnia Ghetto transport were holders of South American passports; a few held British papers from Eretz Yisrael. They organized the group in order to request flour for making matza in honour of the approaching Passover holiday. They addressed their written request to the camp commandant, suggesting that instead of their daily ration of bread they be given flour from which they could bake matza. in this way they would not strain the camp food supplies. Each of the seventy people signed the petition, and the Rabbi of Bluzhov, Rabbi Israel Spira, an old-timer in Bergen-Belsen, was selected as the group's spokesperson.

Adolf Haas, the camp commandant, read the petition carefully, then looked at the rabbi with open contempt and ridicule. "I will forward the request to Berlin," he said, after a long silence, while nonchalantly toying with his revolver, "and we will act according to their instructions."

Days passed and there was no reply from Berlin. With each passing day, the signers of the petition became more depressed. Some were convinced that they had made a grave mistake by signing the petition, for in doing so, they separated themselves from the rest of the inmates and probably signed their own death sentence, thus making their own "selection." Knowing from their past experience that the Germans set apart the Jewish holidays as days of horror, torture, and death, the seventy petition signers feared that they would probably be the Passover sacrifice, the Paschal lambs of Bergen-Belsen. Passover was only a few days awat and the reply from Berlin had not yet arrived. At the height of their despair, when all hope had appeared lost and a bitter fate seemed inevitable, two tall S.S. men with two huge dogs briskly entered the section for foreign nationals. They summoned the Rabbi of Bluzhov to the commandant. In those dark days a summons by an S.S. officer cleared spelled one thing for a Jew: death. The rabbi parted from his friends and began reciting th Viduy, the prayer one reciteds before death, as he walked in the direction of the commandant's office.

Camp cap in hand, the rabbi stood before the commandant and listened to what he had to say: "As always, Berlin is generous with the Jews, You can bake your religious bread." The rabbi remained standing, waiting for the horrible decree to follow the commandant's statement, but to the rabbi's great amazement, none did.

Instead, the camp commandant called in a few inmates from another section in camp who were already waiting at the office entrance, and ordered them to help the rabbi build a small oven for baking matza in the section of the foreign nationals. The rabbi thanked the commandant and rushed back to the barracks in disbelief that they had indeed been granted permission to bake matza.

The building of the oven began with feverish haste, the chasidim fearing that the camp commandant would change his mind at any minute and stop them. In the few days before Passover, matza was baked from the meager rationed flour, matza that only in name resembled the pre-World War II matza baked at home. But the people were thrilled with the shapeless black matza, especially for the children's sake, so they might see and learn that a holiday is observed even in the Valley of Death.

Passover arrived. A seder was arranged in one of the barracks. Three-tiered wooden bunk beds served as tables and as traditional seats for reclining. These precious unbroken matzas were placed on the table. An old, dented, broken pot was used as the ceremonial seder plate. On it there were no roasted shank bone, no egg, no charoset, no traditional greens, only a boiled potato given by a kind old German who worked at the showers.

But there was no shortage of bitter herbs; bitterness was in abundance. The suffering of the Jews was reflected in their eyes.

The Rabbi of Bluzhov sat at the head of the table. He was surrounded by a group of young children and a few adults. The rabbi began to recite the Hagada from memory.

He uncovered the matza, lifted the ceremonial plate, and began to tell the story of the Exodus.

"This is the bread of affliction that our fathers ate in the land of Egypt. All who are hungered - let them come and eat, all who are needy - let them come and celebrate Passover. Now we are here; next year may we be in the Land of Israel! Now we are slaves; next year may we be free men!"

The youngest of the children asked the Four Questions, his sweet childish voice chanting the traditional melody "Why is this night different from all other nights? For on all other nights we eat either bread or matza, but tonight only matza."

It was dark in the barracks. The moon's silvery, pale glow was reflected on the pale faces. It was as if the tears that silently streamed down their cheeks were flowing towards the legendary angel with the huge jug of tears, which when filled to the brim would signal the end of human suffering.

As is customary, the rabbi began to explain the meaning of Passover in response to the Four Questions. But on the seder night in Bergen-Belsen, the ancient questions of the Hagada assumed a unique meaning.

"Night," said the rabbi, "means exile, darkness, suffering. Morning means light, hope, redemption. Why is this night different from all other nights? Whyis this suffering, the Holocaust, different from all the previous sufferings of the Jewish People?" No one attempted to respond to the rabbi's questions. Rabbi Israel Spira continued.

"For on all other nights we eat neither bread nor matza, but tonight only matza. Bread is leavened; it has height. Matza is unleavened and is totally flat. During all our previous sufferings, during all our previous nights in exile, we Jews had bread and matza. We had moments of bread, of creativity, and light, and moments of matza, of suffering and despair. But tonight, the night of the Holocaust, we experience our greatest suffering. We have reached the depths of the abyss, the nadir of humiliation. Tonight we have only matza, we have no moments of relief, not a moment of respite for our humiliated spirits...but do not despair, my young friends."

The rabbi continued in a forceful voice full of faith. "For this is also the beginning of our redemption. We are slaves who served Pharoah in Egypt. Slaves in Hebrew are "avadim;" the Hebrew letters of the word "avadim" form an acronym for the Hebrew phrase: David the son of Jesse, your servant, your Messiah. Thus, even in our state of slavery, we find intimations of our eventual freedom through the coming of the messiah.

"We who are witnessing the darknest night in history, the lowest moment of civilization, we also witness the great light of redepmtion, for being the great ligh there will be a long night, as was promised by our Prophets. 'But it shall come to pass, that at evening time there shall be light,' and 'The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light; they that dwelt in the land of the shadow of death, upon them hath the light shined." It was to us, my dear children, that our prophets have spoken, to us who dwell in the shadow of death, to us who will live to witness the great light of redemption."

The seder concluded. Somewhere above, the silvery glow of the moon was dimmed by dark clouds. The rabbi of Bluzhov kissed each child on the forehead and reassured them that the darknest night of mankind would be followed by the brightest of all days.

As the children returned to their barracks, slaves of a modern Pharoah amidst a desert of mankind, they were sure that the sounds of the Messiah's footsteps were echoing in the sounds of their own steps on the blood-soaked earth of Bergen-Belsen.

Heard at the house of the Grand Rabbi of Bluzhov, Rabbi Israel Spira, June 22, 1975, from Eliach, Yaffa, Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust, New York, 1982, pages 16-19.

Shlomo Wakstok – Passover in Siberia (Kalisz, Poland)

Yosef Balsam – Passover in Siberia (Lancut, Poland)

Dr. Leiben's Sacrifice for Passover

Dr. Leiben's Sacrifice for Passover

Dr. Shlomo Menachem Leiben was born in Prague, Czechoslovakia. His father was Gavriel Leiben. He received both a Torah and general education in his home. His family had been in Prague for a long time and were descendants of the Baal Tosfot Yom Tov.

In 5673 (1913), Dr. Shlomo Leiben married his wife, the eldest daughter of Rabbi Sinai Shiffer, who was the head of the Beit Din (Jewish court) in Karlsruhe, Germany. He studied medical theory in Berlin, and upon his return to Prague began to practice his profession. Working in his profession was a kind of holy work for him. All he cared about was helping those in need. In fact, Dr. Leiben healed not only the body but also the soul. He refused to accept payment from the poor. He also gave them medicine for free, and if he saw that there was not a penny in the house he visited, he left money there as well. Therefore, it is no wonder that his home was a place that benefitted the poor and the oppressed, and they knew they would receive cordial, compassionate, and loyal care there.

Over time, his apartment became too small for all the Jews who came to him for their needed treatments. The community in in Prague made gave him two rooms in one of its buildings that served as an "ambulatorium", where he received patients before noon.

A new chapter in Dr. Leiben's life was the period of German rule in Prague. The testimony of a Jewish businesswoman in Prague, Ms. Irma Polak ("The Echo", Sivan 5712/1952) describes Dr. Leiben's devotion to the people of Israel and to the Torah under the shadow of the occupation: "Dr. Leiben maintained his mental balance and immediately began to act. One of the first orders of the occupiers was that the Jewish patients must immediately leave all hospitals. Dr. Leiben immediately vacated the community's orphanage, recruited Jewish doctors, and established a Jewish hospital within 24 hours. From that point, Dr. Leiben worked at a feverish pace. He established several branches of the hospital, homes for the elderly, daycare centers, and other institutions. His physical and mental powers, it seems, exceeded the limits of man. I helped him in these actions, full of admiration for his initiative and energy, and above all - for the courage he showed in his meetings with the Nazis. He stood before them, as G-d's creation, in the face of blasphemers and defamers of human dignity. The Nazis placed a mine inside the 'Altenoy Shul' synagogue, and the synagogue's beadle found it at night. Frightened, he ran to call Dr. Leiban who hurried and without hesitation took the mine out of the building. Near Passover, the Nazis ordered the closure of Dr. Leiben's public kitchen. At five o'clock in the morning I woke up to loud ringing. Dr. Leiben's wife stood at the door. She was trembling all over, and told me the reason for her visit at this unusual hour. Her husband decided, against the Nazi order, to distribute the matza at the kitchen. She demanded that I use all the influence I had, in her opinion, to convince her husband to stop doing this and endagering his life. I immediately went to the kitchen and found him in the storeroom, helping to open the boxes of matza. 'Do you think' - I asked him - 'that this act of yours, which endangers you and your helpers, might please G-d? You are crossing the line!' I dared to raise my voice out of great emotion: 'You are doing the a mitzva that causes damage!' My warning was of no use. He distributed the matza and the Germans knew nothing about it."

Dr. Leiben was imprisoned in the jail in Prague, transferred to Theresienstadt, and from there - to the Dachau concentration camp. In the letters he sent home from Dachau, they discovered hidden messaged using tiny dots. In this way, he sent them a request to send him a package of clothing, and to bury crumbs of matza shmura (matza that is watched during the entire production) inside his gloves crumbs so that he could fulfill the mitzvah of eating matza. However, before Passover came, Dr. Leiben was murdered by the Nazis on the second day of Nisan 5702 (March 20, 1942).

These I will Remember 7, pages 252-257

A Jewish youth helps to bake matza in a DP camp in Austria

Women baking matzah in the Warsaw Ghetto

The Healing Matza of the Klausenberger Rebbe

The Healing Matza of the Klausenberger Rebbe

Meldorf, Germany, Passover eve 5705 (1945).

In those difficult days, when I was hospitalized in the "hospital" barracks in the camp, hunger was our constant companion. Even those hospitalized in the "hospital" received only meager portions of food, and even the water was given sparingly. Therefore, many of the hospitalized people perished from both hunger and disease.

While I was still hospitalized, with my life hanging by a string, a real life and death situation, the days of Passover came and went. We didn't even dare to dream about matza, we wished only for a little chametz crumbs to revive our souls. My illness got the better of me, I lay exhausted, with my eyes closed, and imagined the near end.

"It is the eve of Passover today" - I heard a familiar voice near me. I opened my eyes and saw the Klausenberger Rebbe, standing by my bed.

While he was telling me to be strong and giving me a number of instructions on how to be careful regarding eating chametz (leaven) on Passover, I shouted at him: "Indeed, I wish I could get a piece of leaven to eat!"

The Rebbe, who secretly slipped into the "hospital" barracks, had to continue on his way for fear that the Nazis would notice his actions, but he still said to me: "Aharon, my love, in spite of everything you got stronger! Don't lose heart and God will save you!"

After being surprised by the sudden visit, I pondered in my heart: "How is it that the Rebbe, who himself was surrounded by the sea of troubles and torments that surrounded him in the same Valley of Tears, had no other concern at the time except the concern of not failing to by eating chametz on Pesach?!"

A few hours later, the rebbe again slipped into the "hospital" barrack, after carefully checking that he was not being followed. He approached me, handed me a piece of matzah that he carefully pulled out from under his clothes, and quickly left the barrack.

I held the piece of matzah in my emaciated hands, as tears welled up in my eyes, and in my ears still ring the few words the Rebbe said to me: "May you have the matza of healing…"

Indeed, I testify that that piece of "healing matza" was a miracle cure for my ailments. After I ate it, there was a change for the better in my health, day by day I got stronger until I could walk on my feet like a human. Less than a month later we were freed from the camp along with the rest of the Jews, the survivors!

Testimony of Rabbi Aharon Furst, Bnei Brak, in Shema Yisrael: Encyclopedia for Documenting and Commemorating Acts of Self-Sacrifice in Ghettos and Camps, Shema Yisrael Institute, Bnei Brak, 5760 (2000), page 214.

Shlomo Cohen – Passover in the Russian Prison (Bielic, Galicia)

Chaim Binyamini – Baking Matzah in Bergen-Belsen (Budapest, Hungary)

A Passover seder in the Feldafing DP camp in Germany

Nachman Bistritz – Passover (Krasna – The Hungarian-Romanian Border)

Akiva Goldshtof's Matzas of Faith

Akiva Goldshtof's Matzas of Faith

It was in the days of World War II, during the Nazi occupation and in the concentration camps with their terrible violence. One day, Akiva Goldshtof arrived in a group that was transferred from the infamous Plaszow camp near Krakow, to the camp in Starachowice. From the first moment he attracted attention due to his noble appearance. He was wearing an old coat, but it was spotlessly clean.

Yosef Friedenson (the son of Eliezer Gerson Friedenson, one of the heads of Agudath Israel and founder of Bnos Agudath Israel in Poland, and the editor of the "Bais Yaakov" monthly magazine) who was already a veteran in the camp, became interested in him, felt that he was a precious Jew, a chassid and an aristocrat, even if he was already beardless.

In the Starachowice camp, like any other camp, there were departments with hard work, and supervisors or "meisters" - evil men who bullied and harassed the prisoners, and there were easier jobs. Friedenson thought that action should be taken to place Akiva in the department of the German Bruno Papa, the manager of the blacksmith shop where 120 Jews were employed, whom Friedenson considered to be a Righteous Among the Nations.

However, the blacksmith shop had more workers than the norm, and this was only thanks to the above-mentioned manager who treated his prisoners in a humane manner. So that his superiors would not raise complaints against him, he decided not to accept any more workers. And here the camp council tasked Friedenson to arrange with Bruno the acceptance of Akiva into his department. The chances seemed slim. Nevertheless, Friedenson went to the manager's office to recommend to him that Akiva be placed in the blacksmith shop.

Bruno Papa's first reaction was completely negative. "The people of the camp council are brain-dead - he claimed - they are abusing my good will to help. It won't work anymore."

However, when he saw Akiva, Bruno Papa had a sympathetic smile on his face. And the good man hired him. And not only that, he ordered the Polish professional to give him light work, and to hand him over as an assistant to an older Pole who would treat him more gently.

Friedenson testified that throughout all the years he saw his act as a victory that helped this wonderful Jew to be accepted in a comfortable place relative to the conditions in the camp. And Akiva rewarded him with something that in those days he could not have received from anyone else - an abundance of influence that forged "Yiddishkeit" (Jewishness, from a religious perspective) in him.

In the camp itself, Akiva remained a complete Jew, a Hasid in all ways. He was upright. He always adhered to Hashem (G-d). His mincha and maariv prayers were recited deeping, and probably with great intention. He lived on dry food. He was not seen standing in line to receive the daily soup. It was known in the camp that he strictly observed kashrut. Akiva was in the camp without a beard, but a Hasidic appearance shone from him. In the imagination, one could see him as a father, or a grandfather of days gone by, a Jew like any Jew in a chasidic shtibel (small synagogue), wearing a shtreimel or a spodik (2 types of fur hats). He had an abundance of reverence for God, and influenced others, reminding those around him of the obligations towards G-d: to pray and not to forget to make a blessing.

As Pesach 5704 (1944) approached, Akiva had the idea to bake matza. He suggested to Fridenson that he should ask permission for this from Bruno Papa. To be honest, he had already taken care of himself weeks earlier, and he had a good amount of matza. However, he wanted the other to get the mitzvah of eating matza, explaining to Friedenson that the mechanical ovens in the locksmith were very suitable for this.

Friedenson went to Papa, brought the request before him. At first, Papa he chuckled and asked: "Don't you have other worries?" But after addressing him in the name of Akiva Goldshtof, he changed his tone, and asked if he had any flour for baking matza. Finally, the good German himself took care of it. One farmer with whom he made a deal provided the flour that was needed to bake the matza. On the first day of Passover, while they were having breakfast, Bruno Papa came in and saw the people eating the matzah, and the portions of bread laid out, and nobody had touched them. He turned to the diners and asked: "What about you? After all, this is non-nutritious food, you will die with your matza, if you do not eat the bread." No one answered. And he approached Akiva Goldshtof and said to him: "You are an older and wiser man, answer me: Has not the good G-d left you?"

Akiva got up from his seat, looked into the eyes of the German, and as if not in his own voice, answered him in eloquent German: "No! Mr. Director, absolutely not, and forever not!" And when he was not sure that the German had heard well, he repeated his words once more. Bruno Papa remained standing as if nailed to his place, opened his eyes, spread his hands. He couldn't find words to respond to Akiva. Finally, the he said: "I wish you were right."

Gerenstein Yechiel (editor), Sanctifiers of G-d's Name: Encyclopedia, Ganzach Kiddush Hashem, Bnei Brak 5766/2006, pages 177-179

A Passover seder in the shelter for new residents at Leszno 6 in the Warsaw Ghetto

An underground Passover seder in Amsterdam, Holland

Passover in the Forest

Passover in the Forest

According to the calendar I had, kept in my "Derech HaChaim" siddur (prayerbook), we knew that the next night was the Seder night. "Sheinakeh, get some sleep, you worked hard all night," I told her, "we need to organize a seder tonight. We need to save some energy." We allowed ourselves a little nap in the afternoon.

It was Sheinakeh who woke up first. "But how will we organize?", she wondered, "We have nothing but potatoes and eggs, we have neither candles nor oil, and in general…?" - "And what do we lack? Really, what do we lack?! Except for matzah, we don't lack anything. We have more than enough maror, don't we? We have potatoes." "And wine?" Elka wondered, "Where are the four glasses?" - "Four cups? And we are drinking many cups now! I do not remember at this moment the four words about redemption in memory of which we drink the cups, but we have been redeemed, we have been saved, we have been redeemed a thousand times from death! Is not our heart crying out for the wine of redemption of this moment? We were redeemed and our ancestors were redeemed; my father was redeemed a year ago. Yesterday I passed by his grave: the grave is calm and spring buds are already rising. My mother was also redeemed a few weeks ago…" - "And mine," answered Elka… Sheinekeh understood; they had all been redeemed.

Heavy snow began to spread a white tablecloth for the holiday. We recited the parts of the Hagada that we had memorized, and even the trees participated with us in the secret chants. Tears of joy fell on us from their tops. We ate chilled potatoes, and sweetened the seder feast with hard-boiled eggs. We sat in the cold of the night, and did not feel it. The warmth of our hearts illuminated us from within, and from the outside the stars shone above us, like crystal chandeliers on the seder table. The passages of the Hagada were spoken in a whisper, just as all our conversations in the forest were in a whisper. No other woman could hear her friend's murmur. Only the bark of the tree we were leaning against caught on to the words of the Hagada. Each of us told her own Passover Hagada. Various Passover sequences passed through our imaginations, first in our fathers' homes and then in our own homes… The tree in front of me is solid, like the body of my late father, and its branches stretch out like the muscles of his bony, seasoned, and strong hands. Like a father in his prayer, the tree moves; I see, yes, the tree in front of me will bend a little, to look at me once more in my silent prayer. A few steps away from me, the figure of the bare trembling birch tree emerges. From among the frozenness, my mother smiles at me, with her head covered with a scarf drooping again and again from fatigue, and her cheeks red from wine. Tonight the family tied a royal crown to her head. Here she came closer and came to me, the queen, thin and modest, winking and smiling at me. It is possible that I am still small in her eyes, waiting for the opportunity to steal the afikoman. The stars dip down and down, hanging on the treetops and trying to set the white snow tablecloth on fire. However, the partisan black night chases them away. The light, we are not allowed. Our path will be illuminated by the inner light in us. I know that each of my friends is thinking about her beloved relatives right now. It was a trace of this warmth that guarded us and captured us throughout that night, where the three of us sat huddled and whispering, reciting large passages from the Hagada. We hardly spoke that whole night, woman to woman. But it was a happy night. Triple happiness united us. Not a single tear was shed, not a single sigh was heard. Here the stars started disappearing one by one.

The first part of Passover rose and shone. We left some potatoes, onions, and hard-boiled eggs from the previous night. With them we had a kosher and fancy holiday meal. While we were sitting under the canopy of heaven, I solemnly called out to the rest of the diners: "Know, dear friends, that we have been saved from a famine. If we all manage to hold back and not taste the bread, God will be with us and save us." In the secret of my heart, I was afraid that some of them might take a bite of the bread when no one was looking. "We will try, we will consider you…", they answered me.

Chol hamoed (the intermediate days of the holiday) passed, the last days of the holiday arrived. Out of curiosity, I approached the hiding place for the bread. Many doubts gnawed at me: Would I find the whole load? Did my friends think of me as they promised? And here, a surprise! The loaf of bread was intact, just as it was eight days ago.

"Look and see, Lord of the world, your people, your children. All of us together and each one individually - full of commandments like a pomegranate even in the shadow of death."

Schlosberg Liba Ahuva, From the Heart of the Black Fire: The Words from the Daughter of the Town of Radom, an Ember that Survived, Jerusalem 5748 (1988), pages 100-102.

Eliyahu Reisman – The Miracle of Rescue on the Seder Night (Tiszakorod, Hungary)

Passover 5704 (1944) in Bergen-Belsen

Passover 5704 (1944) in Bergen-Belsen

On the 7th of Shvat 5704 (Feb. 1st 1944), the surviving members of the Emanuel family were deported from the Westerbork transit camp to the Bergen-Belsen camp. They were housed in barrack 11 and had to face the double challenge of staying alive and remaining Jews. Passover 1944 illustrated this struggle in its full force.

A few days after Purim, the question arose: what will we eat on the eight days of Passover? Is it possible to avoid eating the portions of bread during Passover and settle for the soup and the unpeeled potatoes that are given out for lunch?

The rabbis of the camp ruled that the prohibition of eating chametz on Pesach was not applicable in the current situation because of the mitzvah of "and live by them", (to live by the mitzvahs and not be endangered by them) and wrote a special "Yehi Ratzon" (May it be Your will) prayer that the people of the camp should say before eating chametz: "Our Father in heaven, here is manifest and known before you that our desire is to do Your will and to celebrate Passover by eating matzah and observing the prohibition of chametz, But for this our heart has prayed that slavery is holding us back and we are in danger of our lives. We are ready and willing to fulfill your commandments 'and live by them and not die by them' and beware of the warning 'keep yourself and keep your soul very much', and therefore our prayer to you is that we may live and live and be redeemed soon to keep your laws and be able to do your will as your servants with a whole heart, Amen".

Due to the impossibility of copying and distributing the prayer in sufficient quantities, a few copies of the "Yehi Ratzon" were distributed amongst the camp residents. My brother Elchanan volunteered to copy it several times in his own handwriting. He made sure to copy the prayer with punctuation and precision, and this after the arduous work of cutting down trees for twelve hours a day, and despite his strong desire not to eat chametz on Pesach. The famous copy of the "Yehi Ratzon" that appeared in various documents is a photocopy of Elchanan's handwriting. This piece of paper is also evidence of the supreme devotion for the common good and for the preservation of the Torah during the Holocaust.

Without doubting the validity of the permission to eat bread, we decided that we would try to avoid eating chametz on Pesach as much as possible and "organize" for it. There were people who heard about our intention to avoid eating chametz and suggested to us that they would accept our portions of bread on Passover and in return give us boiled potatoes, even more than the daily portion. Father rejected this solution and said that it is not possible for us to observe the prohibition of eating chametz on Pesach by giving our bread to others. After all, in the end, it would be Jews who would eat our bread on Passover.

Another proposal was made. I was employed in service work inside the camp and also helped in receiving the food rations for the men, father and brothers. Father asked me to try and store food for Passover. About three weeks before Passover, I began to set aside two potatoes from each of our food rations every day. In total, I accumulated ten potatoes every day. The problem arose of how to keep them for a period of almost a month. We also found a solution to this problem by drying the potatoes on an oven that stood in our shack. Before the holiday, I made cakes from the potatoes I had stored and this was the food we ate throughout the holiday, potato "cakes" in the morning and evening, and at noon fresh potatoes in the skin from the daily ration. Of course, this food was not strictly kosher for Passover, but we managed not to eat chametz or a mixture of chametz. Most of the people of the hut did not know at all that the members of the Emanuel family were not eating bread on Passover. We did not take the bread that was distributed on Passover. We told the person responsible for distributing the bread where the suitcase to store the bread was. Before Pesach we made the suitcase hefker (not beloning to a specific owner), and took the bread from it only after the holiday.

The potato cakes lasted until the last day of chol hamoed (the intermeddiate days of Passover), and I did not know what we would eat on the seventh and eighth day. And here, on the last day of chol hamoed, a new shipment of Jews arrived from Holland, and among those who arrived were members of the Hirschman family, who were our neighbors in Utrecht. When they heard from me that we had no food left for the last two days of the holiday, they gave us a bag of beans and that's how the problem was solved.

Before Passover, Baruch obtained some flour from Jews who came to the camp from the city of Benghazi, Libya. We prepared to bake an olive-sized matza for each person for the seder night. Elchanan placed a glass bottle in water for three days, and the evening before baking he prepared "mayin shelanu" (water gathered the night before preparing the matza). My mother organized a number of tools for making the dough, we got wood and checked if the stove in the shack was suitable for heating. Several people joined in baking the matzah. A young man by the name of Yosef Adler was in charge of the oven, Rabbi A.I. Davids, may G-d avenge his blood, oversaw the kneading of my mother's dough and everyone contributed to the success of the operation. We put a surface made of tin into the oven and placed the dough on it, which was carefully prepared according to all of the Jewish laws. During the baking, neighbours in the hut brought more flour, and the "mayin shelanu" was not enough. Rabbi Davids advised that we could add regular water to the bottle as long as there was "mayin shelanu" in it. Baruch and Yaakov Yehoshua stood outside and kept watch. Suddenly the call "achtung!" (Attention!) was heard. The door opened and to everyone's astonishment, one of the SS men entered. He asked what we were doing. My mother managed to remove some of the dishes, and others answered the German that we are making a birthday cake! Luckily for us, this Nazi soldier was one of the oldest in the camp staff. He turned and left.

Seder night passed without interruption. We observed the mitzvot of four cups by drinking four cups of tea. We read the Hagada and each one ate some matzah. At the end we said with intention: "Pour out your anger on the nation… you will persecute them and destroy them under the sky of God."

Shmuel Emanuel, It Will Be Told to Generations: The Experiences of a Family in the Holocaust, Jerusalem 5754 (1994), pages 122-124.

Yosef Yeshayahu Bonder – Passover in Hiding (Bardejov, Czechoslovakia)

Rabbi Yosef Bramson - Passover in Bergen-Belsen (Franeker, Holland)

Meir Halberstam - Passover in Siberia (Sanz, Galicia)

Tzvi Birenbaum - Passover in the Westerbork Camp (Germany - Holland)

Yaakov Yehoshua - Baking Matzah in the Westerbork Camp (Germany - Holland)

Shmuel and Mordechai Basch - Passover Night in Mauthausen (Spinka, Romania)