Shabbat is a day of rest and exaltation for the souls of Jewish people, the day from which Jews draw strength for the days to come: “Shabbat, sweetness of souls, the seventh day, delight of spirit and bliss of souls.” The Nazis were aware of this and did everything they could to use these days for decrees, deportations, and forced labor. But the Jews did not give up and did as much as they could to manage calendars, mark Shabbat and keep it. Even non-observant Jews went above and beyond to keep Shabbat. This was the way of the tortured and humiliated prisoners to expr [Read more]

Jews returning from prayers at the Great Synagogue on Walborska Street in the Balut district of Lodz, Poland

Moshe Kugler – A Hunger Strike and the Shabbat Meal (Sopron, Hungary)

The Mincha Prayer on Shabbat

The Mincha Prayer on Shabbat

Bergen-Belsen Camp

Shabbat afternoon in summer 5704 (1944). The hour was 6:30 PM. Hundreds of Jews were returning from work, run down and starving. Upon their entry through the camp gate, the returnees were counted. Out of hatred, they were counted upon going out and returning from work.

Father did not return from work at that time and did not pray Mincha with us. The members of his group, the "Benedict" group, who were all middle-aged, were punished and had to stand for a few more hours at the camp gate. Abuse. Hadn't enough trees been cut down from morning to evening? And maybe the Germans found out that they don't work as fast on Saturday as they did during the week? Father saw to it that during the week they would hide a certain amount of sawn wood, in order to reduce work on Shabbat. Maybe this was discovered?

Thus they stood, exhausted and broken, near the camp gate. The SS guard In the watchtower made sure that the people stood still, without moving from their place. An hour passed. The SS guard came descended from the watchtower and the Jews feared greatly. Maybe he came down to beat them? The guard walked past them and walked down the road towards the administration buildings. The members of the group were registered and there was no fear that they would move from their place, but nevertheless they felt a sense of well-being. The guard disappeared at the end of the road and so the Jews could stand more comfortably and even exchange words. At that moment, father surprised the members of the group and called out pleasantly:

"Ashrei yoshvei beitecha od yehalelucha sela...U'va le'Zion goel...V'ani zot briti otam amar Hashem...Yitgadal v'yitkadash shmay raba...Ata echad u'shimcha echad u'mi ke'amcha Yisrael...V'al menuchatam yekadishu et shemecha...retzay bemenuchateinu kadsheinu be'mitzvotecha ve'ten chalkeinu be'toratecha sabeinu me'tuvecha ve'samchenu be'yeshuatecha...chen va'chessed ve'rachamim aleinu v'al kol Yisrael amecha" (excerpts from the Mincha prayer).

"When it was time to present the meal offering (known as 'Mincha')" (Kings I 18:36)

The SS man saw and approached. The people stood straight again until late on Saturday night.

The next day, I heard the story of what happened from one of the members of the group, Mr. Levi Van-Leeuwen, a member of the Chevra Kadisha (burial society) of the Hague. He added: "I never heard such a Mincha prayer!"

(It Will be Told for Generations, Yonah Emmanuel)

Bracha Sternberg – Shabbat Candles in the Siberian Frost (Hrubieszew, Poland)

Jews exiting a synagogue in Amsterdam following Shabbat prayers

Esther Katz – The Shacharit Prayer in the Forest (Rudzin, Poland)

מסירות נפש לשמירת שבת בגטו וילנה

מסירות נפש לשמירת שבת בגטו וילנה

הרב קלונימוס קלמן פרבר ז"ל תלמיד ישיבת ראדין שזכה להסתופף בצילו של מרון החפץ חיים זיע"א שהה בזמן השואה הנוראה בגטו וילנה. מתוך פרקי זכרונותיו ליקטנו שני עובדות אודות שמירת שבת קודש מתוך מסירות נפש.

...בנתיים באה השבת. ועלינו, על כל היחידה היה להכין אוכל ליום השבת, וכן ליום ראשון, ביום שיננו עובדים. כבר בררתי בגטו את ההלכה, את הדינים הנוגעים לשמירת שבת. יש לנו קבוצה של בני תורה, אנו נפגשים כל יומיים כמעט בגטו. בתוך הקבוצה גם בנין של הרב יוסף שוב. שלום ויעקב. וכן שני תלמידים של רבי וועלוועלע בריסקער ראש ישיבת בריסק, שנשארו בוילנה ולא הספיקו לצאת לשנחאי. עפי" רוב מבררים אנו הלכות שבת, טרפות וכדומה. אחרי ברורים סיכמנו כי העבודה בחצר, במכונה לחיתוך התבן לשם עירבוב המספוא בשביל הבהמות יש במלאכה זו בשבת משום איסור דאורייתא. אי לכך תכננתי והתחלתי להכין את כלל העובדים יומיים לפני שבת, כדי שביום שישי נהיה כולנו פנויים לעבודה זו, הפעלת המכונה לחיתוך התבן ונכין מלאי הגון , ולא יכשל שום יהודי באיסור דאוריתא בשבת....

(זכור ח"ג עמ' 152)

Yisrael Orlanski – Shaleshudis (the 3rd Shabbat meal) (Bielsk, Poland)

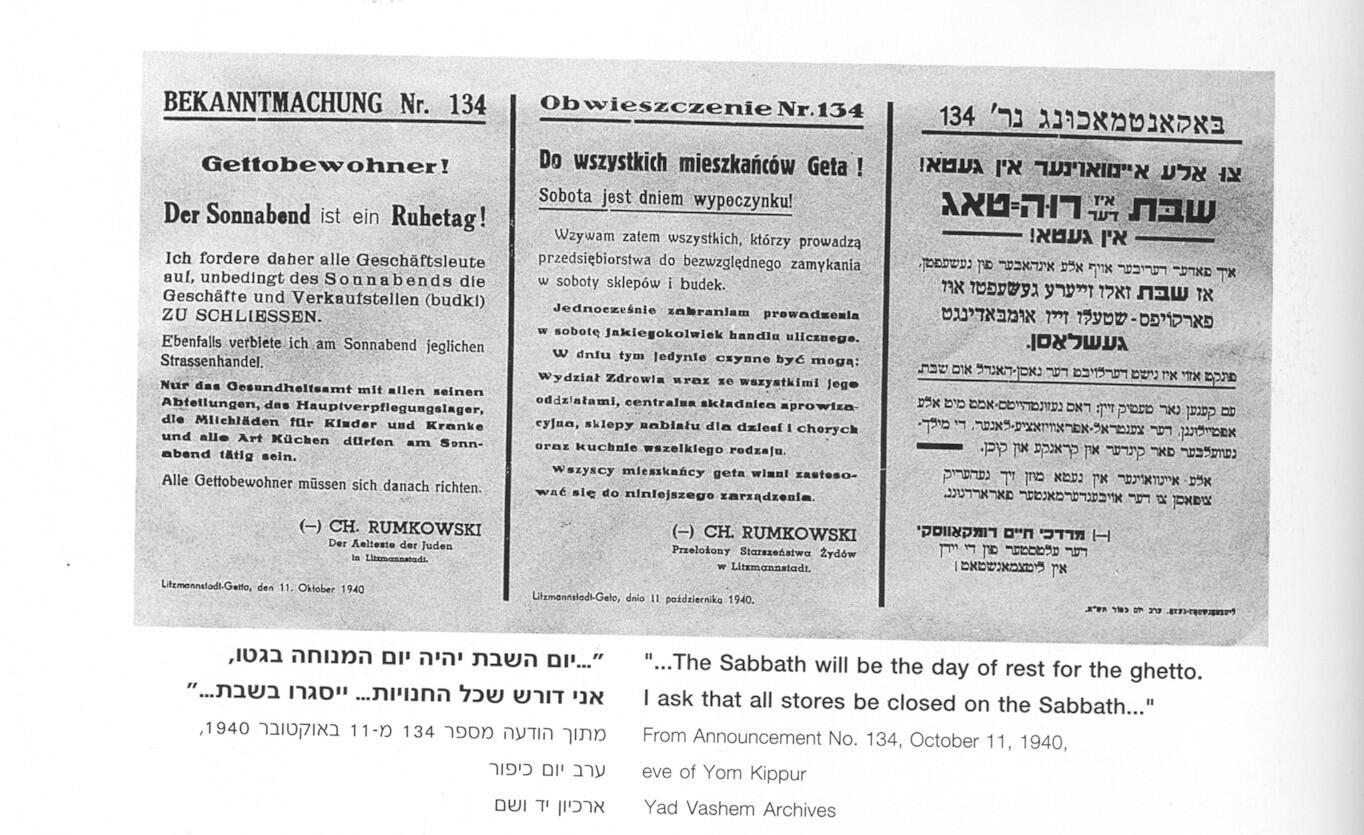

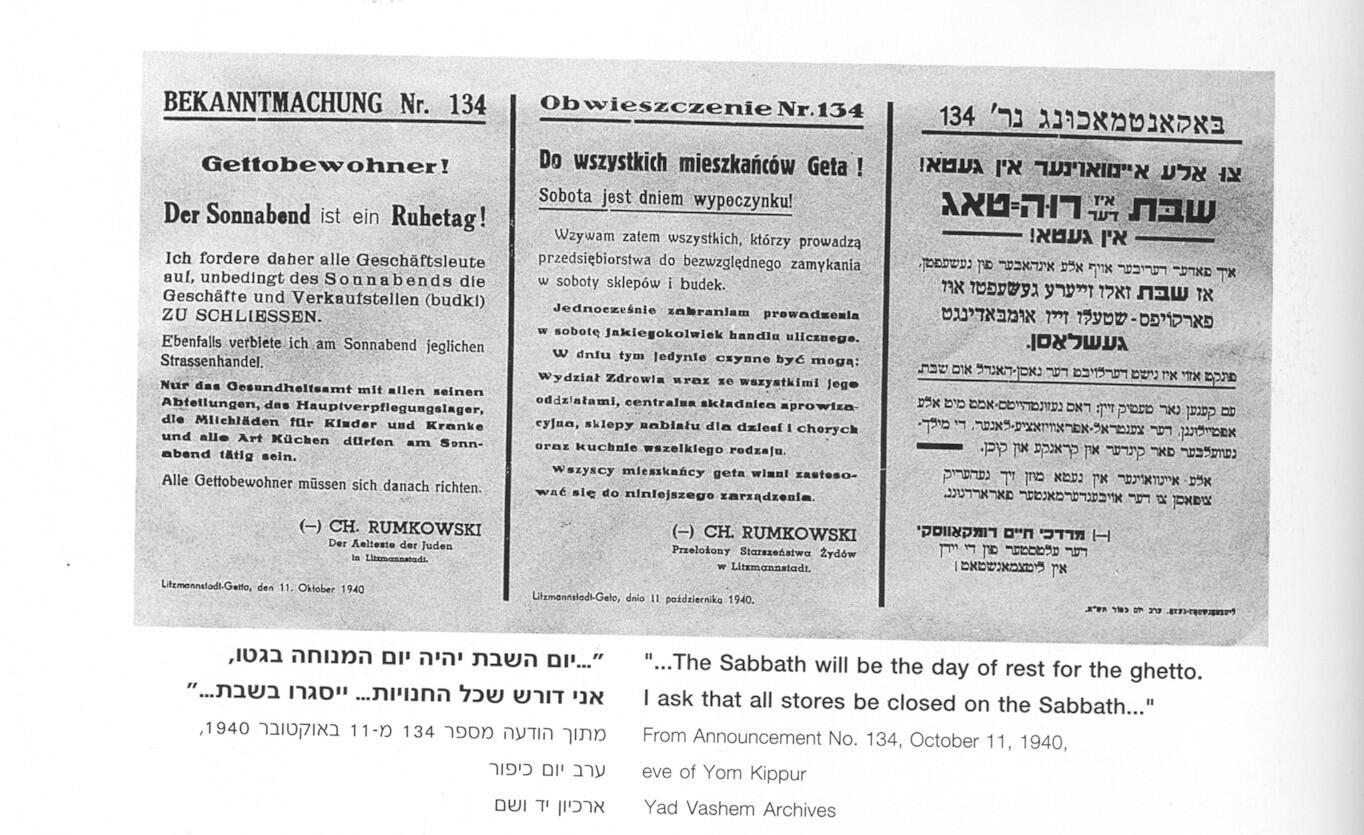

An announcement from the Lodz Ghetto Judenrat stating that Shabbat is a complete day of rest

The Customs of Prayer on Shabbat

The Customs of Prayer on Shabbat

Bergen-Belsen Camp

In our barrack, Barrack 11, we prayed the Shacharit prayer each morning in a minyan (prayer quorum) before work. We prayed with a tallit and tefillin. On Mondays and Thursdays, we read from a Torah belonging to David Naftali Abrahams. When he was sent to the camp, he gave up bringing a bag of clothing and instead brought a package containing a Torah! There were other righteous men who brought with them hidden Torahs and in their merit we were able to read from the Torah in several minyans in Bergen-Belsen. My father was careful that the minyan would not disturb those who wanted to continue sleeping until it was time for role call.

On Fridays, we prayed the prayer for the start of Shabbat after we returned from work at dusk, and in the first months we did not change out of our work clothes in honour of Shabbat...We brought in Shabbat with hope because "You have dwelt in the Valley of Tears for too long, He will show the compassion He has felt...Those who plunder you shall become a spoil, and all who would devour you shall be far away"(from the prayer upon the start of Shabbat).

A problem arose regarding reading the Torah on Shabbat during the winter months. In the morning it was dark because, of course, we didn't turn on the light on Shabbat (in these barracks there was partial lighting). That's why we read the weekly Torah portion on Shabbat night from a Torah book, without "Aliyot" (people being called up to read to the Torah) and without the Torah blessings. After reading the Torah, we hurried to lie down to sleep, to gather strength for working on the holy Shabbat. On Saturday morning, we prayed the the Shacharit and Musaf prayers, ate quickly, and ran to the work supervisor. We worked on the holy Shabbat day and we attempted not to distract ourselves from it. Sometimes it seemed to us that it was precisely on Shabbat that time stood still and the day seemed so long to us. It was very difficult, and even impossible, to keep thinking all day of how to work with a a change, in a irregular manner (this is done in order to lessen the severity of breaking Shabbat). Here, today is Saturday and you have to work twelve hours, six hours in the morning and six hours in the afternoon. You are required to work, carry, dig, build, on and on, until when? Today is Shabbat, from morning till evening we will remember Shabbat; Shabbat, Shabbat, and nothing but Shabbat!

Did we know before…. how many precious hours there are in one Shabbat, in one Shabbat?

(It Will Be Told for Generations, Yonah Emmanuel)

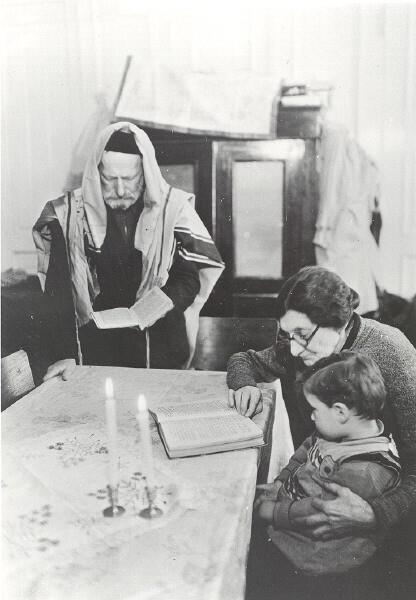

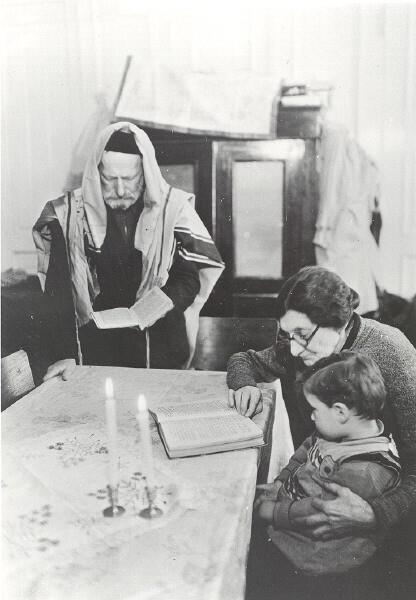

A Shabbat meal in a DP camp

Shabbat - A Precious Treasure (In the Lodz Ghetto)

Shabbat - A Precious Treasure (In the Lodz Ghetto)

We must sanctify the Sabbath, but with what? There were no candles, no wine either, and everyone ate the meager portion of bread in the morning. A white tablecloth was spread on the table in honor of Shabbat. I prayed evening prayer. I finished "On that day the Lord will be one and His Name is one" - I said "Gut Shabbos", and my sisters sat patiently on the bed, I took out the portion of bread that I had saved from the morning and designated for Kiddush for Shabbat. I said Kiddush over the bread and cut it into three parts, for my sisters and me, but they refused to eat. Only after I assured them that there was a pleasant surprise did they eat the bread. And I took out the pot of soup whose smell spread throughout the room.

On Friday, upon my return from the night shift, I found a note on the table and next to it were a few slices of bread, and this is what it said: "To our dear brother, you returned a precious treasure to us - Shabbat, which we almost forgot last Shabbat."

(Yaakov Krieger, I Lived)

Avraham Steinberg – Shabbat in the Train on the Way to Siberia (Jaroslaw, Galicia)

Jewish women in Poland coming from Shabbat prayers

Chana Moskowitz – Shabbat at Home (Bucharest, Romania)

To Kindle the Shabbat Candles

To Kindle the Shabbat Candles

Kovno Ghetto

On the eve of Shabbat Teshuva (the Shabbat between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur) 5702 (1941), when the Jews were preparing for Shabbat, the Germans suddently burst into the ghetto and with roaring voices, mixed with the "Song of Songs," they ordered the Jews to immediately exit their homes. Accompanied by beatings, the Jews were taken out of their homes, without being given the opportunity to equip themselves with clothes and food.

One of the deportees was Ella Szmulewitz, the head of Beit Yaakov of the Kovno Ghetto. She suceeded in taking out her candlesticks with the candles. Her hands were drenched with blood from the Germans' blows, but she did not let go of the Shabbat candles.

As the sun began to set on the western outskirts, these deportees were herded into the infamous Ninth Fort.

There, in that area, Ella Szmulewitz reminded her Jewish brethren that today was Shabbat and that they had to sanctify the Shabbat before they were to santify the Name of G-d (by being killed as Jews). She lit the holy candles - Shabbat candles, blessed them with a murmur of prayer to the exhalted G-d, that He would receive under the protection of the wings of the Shechinah (Divine Presence) these holy souls, who in the very sanctity of the Shabbat would sanctify His Name.

That evening, when the sun had set, these martyrs marched to the Ninth Fort to the sound of "Lecha Dodi" being sung, and among them was Ella Szmulewitz with members of Beit Yaakov.

(Rabbi Ephraim Oshry, Beit Yaakov Journal, Issue 13, Sivan 5720, May/June 1960)

Prof. Reuven Feuerstein – Jewish Families in Romania (Botosani, Romania)

A secular and Jewish calendar printed in the Lodz Ghetto, Poland with the starting times of Shabbat and holidays

Natan Tzvi Baron – The Struggle to Keep Shabbat in Telz (Taurage, Lithuania)

Liberation on Shabbat

Liberation on Shabbat

We were in the detention camp in Cyprus for half a year, when on a cold winter's day we found ourselves on a ship again, headed to Israel. This time it was a short way, and after not much time we arrived near the shores of Haifa. It was winter outside and was cold, and we longed to feel the holy ground under our feet, but…it was Shabbat that day.

"Get off! Get off!" The British soldiers rushed us.

"It is an explicit rule," Leibel reminded us, "It is forbidden to disembark from a ship on Shabbat."

The British were furious and tried to push us out. The people from the Hagana urge us to get off immediately - the Etzel intends to blow up the ship, they said.

"On Shabbat - We will not disembark," Leibel Kutner said on behalf of us all.

The British did not know what to do with us - the group of Jews who refused to disembark from the ship. British soldiers, Jews, and curious people gathered on the beach and stood dumbfounded in front of the "refusals to disembark on Shabbat".

"Leibel! Leibel!" We heard someone yelling from the shore. We all look for who the speaker is. "It's me, Leibel. Me! Your cousin - Moisheleh," the man waved his hand. "Get off! Get off! It's dangerous to stay there."

The man was a relative of Leibel, a relative who was living in Israel who had been recruited to convince us to get off the ship.

"Moisheleh?!.." Leibel smiled at him sweetly, "It's Shabbat today. And we will descerate the ground of this holy land?"

We prayed the Mincha prayer on board and then organized the third Shabbat meal and sang Shabbat songs. The British and other passersby looked at us in disbelief. There was a rumour that the ship was going to explode at any moment while we ate and sang. We continued to sing. There was no fear in us, and the possibility of adhering to G-d's word gave us strength and joy.

When Shabbat ended, we held the havdala post-Shabbat ceremony and calmly disembarked. We had not exploded and the sweet feeling of withstanding a test filled us. The angry British directed us to a transit camp in Atlit. The next day, the newspapers were full of headlines: "Immigrants refuse to get off the ship because of the sanctity of Shabbat."

(Menachem Brickman, "The Felled Forest Will Rejoice")

Bracha Sternberg – The Enjoyment of Shabbat (Hrubieszew, Poland)

Jews praying a Shabbat prayer in a secret synagogue in the Warsaw Ghetto, Poland. At the head of the table, sits Rabbi Kanal.

Menachem Haberman – Shabbat Night (Munkasz, Czechoslovakia)

We Sanctified Shabbat and We Worked

We Sanctified Shabbat and We Worked

Westerbork Camp, Av/Elul 5703, Summer 1943

Despite everything, we found a bit of time to learn Torah. Rabbi Yisrael Goldschmidt gave over a lesson without books. We prayed in a minyan (prayer quorum) and we listened to the Torah readings. On Shabbat mornings, we prayed earlier so that we would have time to get to the roll call for the workers going out of the camp. It was an odd and difficult feeling. "Remember the day of Shabbat to sanctify it." We remembered it, sanctified it, and worked all at the same time.

(It Will Be Told for Generations, Yonah Emmanuel)

Rivka Binyamini – Shabbat in Auschwitz (Nitra, Czechoslovakia)

Prof. Reuven Feuerstein – Botosani, My Birthplace (Botosani, Romania)

The Angel in White in Auschwitz

The Angel in White in Auschwitz

It was the end of the summer of 5703 (1943) in Auschwitz. "The end of the summer is harder than the summer" (Talmub Bavli, Yoma 29:71) is not just an expression. In the barracks you can suffocate, outside the sun is hot, blinding the eyes and hitting the head. You can't get a drop of water to quench your thirst. I am eagerly waiting for the Christian lady who works in the camp kitchen. She promised to bring me a bit of water for the price of today's ration of bread. I'm nervous, maybe she won't come, maybe she won't be able to smuggle it out. The very idea drives me crazy. I feel my tongue stuck to my palate. The streets of the camp are empty at this hour, nine o'clock in the morning. Everyone is working, but we just have to be in the barracks, because according to the law, prisoners start working after three months of being in Auschwitz, and we have only been here for two months. Over time, we are "educated" in discipline, we memorize the way the camp works; twice already I received a reprimand for standing next to the barracks, which resulted in a severe punishment. I finally saw the Christian, my neighbor from Warsaw, I ran towards her with joy. "You have?" - I asked with a tremor. "Yes, but" - I recognized some hesitation in her voice, "I can't give you the water. The portions of bread will be smaller today." My face darkened. I fixed my gaze on the bottle that she took out from under her apron in front of me, as if to tease me and increase the strong desire to drink. "Well what do you want?" - I asked frantically. - "I also want your portion of bread for tomorrow." "Good!" - I answered without thinking, "Give it to me already", I begged her, "Why are you torturing me?" - "Don't forget to give me your bread tomorrow", she repeated her demand. I didn't answer, I didn't hold back, I held the bottle with trembling hands, soon I'll drink… I thought happily. At this moment, the bottle fell from my hand, the water spilled and I also fell unconscious. The Polish camp overseer, Stania, stood by me and wanted to wake me up using her rubber truncheons. The Christian woman was allowed to escape, only on me were questions and blows rained down upon. "I have to admit why I lured a Christian into smuggling water for me. I couldn't answer. I felt my mouth full of blood. She went with me to the head of our barrack, scolding her for allowing me to walk today. "By the way," she continued mockingly, "I studied dentistry at the faculty in Warsaw. I extracted two of her teeth. Take her to a dental clinic now, they will finish the treatment." Margot Klein, the head of our barracks, stood confused and did not understand her words. She tried to ask something, but her words were interrupted by a strong slap on the cheek. "You must go to the dental office. Understand?" Margot was seething. On the way she "honored" me with all kinds of nicknames, by which she lost her grace in Stania's eyes. "You won't forget this." I didn't answer; I followed her, as if my sense of cognition had been dulled. We arrived at the dental clinic.

The dental clinic bordered the hospital secretariat. Only Jewish women worked there, two dentists and two nurses. According to the "law," these Jews were not allowed to practice medicine. They were only permitted to extract without anesthesia, or to apply an iodine substitute to the gums against avitaminosis (oral disease) which spread at lightning speed, due to the poor diet and unsanitary conditions. Considering the special occasion being that the head of my barrack accompanied me, I was admitted without having to wait in line. I saw before me a beautiful, clean room. Full of medicine. The dentist was a gentle woman named Maria Metomaszow, whose whole demeanor was incredibly humane and noble. "What hurts?" she asked softly...I didn't want to see nor did I see anything, only the tap that flashed before my eyes in all sorts of colours..."I want to drink". That's all I could say. Her eyes filled with tears, she understood, she allowed me to drink. At this moment I forgot everything, all the disgrace and humiliation, I gulped more and more of the water, my strength was replaced. Maria applied something to the wound and said painfully: "I know Stania's work." She gave me a cream for the wound. She requested that I hide the cream properly and apply it at night… "I am not allowed to give medicine to the nurses," she commented with a sigh, "but it is difficult for me to adapt to this prohibition which means: cease to be a human being"… then she whispered in my ear: "Any time you can come to me, you will drink water as you wish ". "You brought me back to life," I blurted out, "I did not lose faith in humanity"…

The head of my barrack was impressed by the dentist's attitude. She also changed her tone and said: "Rest a bit and sit on the bench for about half an hour, when you get stronger we will return to the barracks." I sat on the bench in front of the secretariat and the laboratory for special needs… I was intirely immersed in gloomy thoughts, indifferent to my fate. It seemed to me as if I had fallen asleep. It was as if I was daydreaming. Suddenly voices. What happened? What else is in store for me today? What else must I see?

They brought food, warm unsalted water with some grains, the diet for sick people. All the patients left the waiting room of the clinic screaming, pushing each other. Voices could be heard piercing the heavens. At this moment, the image from the morning with the water, in which I was the hero, was forgotten. And those shouts next to the boiler, the image of the brokenness of my people, made me sick to the point of vomiting. At this moment a young girl came out of the secretariat, and she approached the group, it was as if she had touched a magic circle, the voices were silenced! "Who is she?" I asked the people present. "Don't you know?" they looked down on me. "You haven't gotten to know our Tila yet, she is an angel from heaven. A symbol of goodness." They greatly praised her. I got closer to her. Seeing her up close, I realized how much power she held. I saw in front of me a young women around 19 years old, dressed very well, and in her childish eyes was a love without limits for a people, a desire to help, a desire to alleviate pain, and to dress the wounds of torture. She approached the boiler, lovingly distributed the food, filling every spoon that was handed to her. After her work, she approached each one, asked how they were, wrote down their needs, and with an encouraging laugh got ready to go. At this moment she noticed that my eyes were fixed on her and expressed surprise and wonder… surely my face did not bode well. She approached me and asked: "Why did your face fall? Why are you pained?", she reproached to me, "that way you are helping Hitler." I did not understand. "Yes!" She repeated strongly, "He who does not get stronger and loses hope, they are helping him. We must not let our spirits fall, We must overcome!" She was enthusiastic and looked as if she had matured in years.

I told her all that I had seem. "Now, do not tell me anything, stop being bitter. You have been in the camp for two months, and I have been here in the camp for over a year. I know everything, my eyes , my eyes darkened at the horrible sites. Nevertheless, I believe that Jews will remain, and the order of the hour" - she lowered her voice - "is not to lose your spirits, to help, and to make things easier. My job is to sit in the secretariat and write. During the afternoons I dodge the job and go out, I have the satisfaction of giving anything to anyone." "It's strange," I told her, "I just met you and you seem to me to be very close." "Really?!" - she replied happily. "Who else do you know in the camp?" - "In this insane asylum where there is a women's camp, I know Tzila Orlian." Tila jumped up from her seat with joy, "She is my teacher, I met her in Slovakia, I studied there in Bais Yaakov, and we are inseparable." "Oh, Tila, I met your teacher in you, that's all I can tell you"… shouts were heard, the head of the camp called me, I should come back already, Tila accompanied me. "If Tila is interested in you, then it's worth talking to you", Margot complimented me. Who is Tila really?" I asked her, confirmed by her friendly voice, unknown to me until now. And Margot answered: "Tila is one of the best girls I've ever seen, the more she protected her sisters in trouble, the more important she became in the eyes of the Germans. She gives herself up entirely. Distributing her bread among the sick, on the gloomy nights, when everyone is already lying on their bed, Tila walks from barrack to barrack, bringing various pills to the sick, brings food, and brings hot water secretly, at her own risk. She encourages and strengthens. And the main thing is that she does it simplicity and modestly. She's just justifying her exitence: maybe a little? During the selections, she did not rest, she runs to the doctor and begs to save people and get the person out of the clutches as prey. In the last selection, for example, Tila stole ten tickets at night, and by doing so saved ten lives. When it was pointed out to her that she was taking a risk, she replied: 'Even if I die from this, I will be happy, that I will die having lived as a traitor' "… Margot sank to the ground, and continued: "I envy her, I would also like to be like her. I was stunned," she admitted.

When I arrived, I found on the bed articles of clothing, bread, water, and a small note: "See you in the evening". Tila, a faithful help in times of trouble; What joy!

At night the whistle was heard, time to sleep. But I didn't close my eyes, I waited for Tila. I heard noise and realized she was coming. She went from bed to bed and brought what she had promised. When she got to me, she apologized to me for coming at a late hour, because she brought bottled water and went back and forth several times to do so. "You quench the thirst of the daughters of Israel!" - "It's nothing", answered Tila simply, "believe me, if I could do even more and help without limits and restrictions…" "But", I interrupted her words, "your deeds are very great". "My eyes are directed upwards," said Tila with a light laugh, "so that I see only what I have to do, and not what I have done. We make our lives quite bitter by our dimunition, by our lack of mutual understanding and assistance; it is not worth being bad under all conditions and in any situation, and even more so in the camp. I might have been different, G-d forbid, but I have a strong barrier to becoming that way, the commandments of the Torah are for me an inviolable law. We'll talk more practically," she changed the subject of the conversation, "I want to learn a little Nach (the Prophets and Writings sections of the Bible) - do you agree?" "Learn?!" - I was dumbfounded - "Tila you have reached truth through your actions, what others will not even reach through their minds, your wisdom is the wisdom of the heart and deeper than the wisdom of the head." Tila was not impressed by my words and concluded the conversation with the following words: "Once a week we will study. You have free time, you do not work. I will see Tzila Orlian, we will try to get you an easy job." The next day I met with Tzila Orlian, I told her about the impression Tila made on me. I asked her to tell me about Tila's life. Tzila Orlian addressed me and began: "I admire her, even though she is my student. She studied with me in Slovakia, for a short time, at Bais Yaakov. She is from Tesin, she fled during the Nazi occupation to Slovakia, and that's where I met her. During my studies, I knew that every lesson uplifts her. She rose and rose above the whole class. At that time, I didn't know her greatness, I was only impressed by her diligence, until I came here and saw her deep faith, simplicity in her ways of life and consistency in keeping the mitzvot." Through her I understood well the talmudic rabbi, Rabbi Chanina's words: "From I my students, I learned more than from everyone else" (Talmud Bavli, Taanit 7a:12).

Tila was very busy. Before Passover, we dave to prepare a place for conducting the Seder. We do not worry, she will suceed, and she she really did suceed. We sat about fifty girls at the table, in the gloom of the night. We recited the Haggadah by heart.

On the seventh day of Passover, we were amazed. Tila and Tzila Orlean were fired from the secretariat. The one who plotted against them was Wanda, a Pole. They were sent to hard labor. We were pained. The good Tila, a doer of kindness, how will she work hard?! But she was quiet. "I can work too" - she said - "my blood is not redder than your blood, you should only regret that the possibilities for help have decreased a little, but it will still be good!"

For several weeks she carried the food from the kitchen to the barracks, at the end she was assigned as a nurse in the barrack, in this job she felt good. Here she found an extensive way to help others. Her name was glorified amongst us all. As a faithful nurse, she cared for each person.

On Shabbat Eve, she lit candles as a reminder of Shabbat's arrival. A German once passed by the barrack and saw the burning candles. Everyone asked her to extinguish them, but she refused, went out with her head held high and declared: "Today is Shabbat for us and in its honour, I lit candles." We were not punished. Her brave stance influenced him.

One time, Tila turned to me and stated: "I've made up my mind to resign from my job." "Why?" - I asked - "You feel good, and you don't work hard, you just have to go every day with the girls to the clinic", Tila got angry at my answer: "I don't work hard - is that everything? Is that the main point? But I can G-d forbid be a problem for my sisters. They say that another selection is imminent and I will have to, God forbid" - she trembled - "to make a list of the patients".

The next day she requested to be transfered to a job outdoors. Many did not understand her move. After a week it was clarified. They all praised her and expressed their admiration. "Don't think" - Tila told me - "that I am satisfied, because in any case this will be done and sacrifices will be made again. I just could not live with this burden on my shoulders to be a direct cause of people's deaths, G-d forbid. I want to be just a simple soldier. Not a commander."

"Your name will appear in the pages of heroism" - said someone from the audience - "Is this heroism?" Tila turned to ask me - "A wise person's question contains half the answer, dear Tila" - I answered.

(Pesha Sharshevsky, Rays of Light in the Darkness of Hell: A Collection of Stories of Jewish Self-Sacrifice during the Holocaust, Bnei Brak, 5748 (1988), pages 67-78)

Avraham Steinberg – Shabbat in the Train on the Way to Siberia (Jaroslaw, Galicia)

Menachem Haberman – Shabbat in the Town (Muncasz, Czechoslovakia)

The Third Sabbath Meal at Mauthausen

The Third Sabbath Meal at Mauthausen

Ignac of Lipshe, Czechoslovakia, was one of the tens of thousands of concentration camp inmates who were chased on foot across the frozen landscapes of Europe during the winter of 1945. They were driven into the inner lands of Germany and Austria ahead of the advancing front. It seemed as if heaven too had no mercy and unleashed its winter fury with blowing snows and gusting winds on rag-covered, emaciated bodies of the people on the death marches.

Ignac, though only in his teens, was already a veteran of many camps. He was quick to assess the march and its awesom, deadly rhythm. He knew that luck and faith alone could not assure one's survival; that winter and S.S. guards could only be outmaneuvered by the determined will of a Jewish lad. Ignac knew that as long as his feet would carry him and as long as he did not attract attention, life would cling to his wretched body. If his feet failed, the road would be his grave. All his will to live, all his determination to survive now concentrated on his two legs. He commanded them not to stop, not to slip, not to stumble. He became oblivious to the rest of his body as if it had ceased to exist, as if it had dissolved into the biting winds and drifting snows. there was nothing to him but two frostbitten feet, two skinny bones that kept conquering life, meter after meter down the endless, white-shrouded roads. Bodies were slumping and falling to the ground all around gim, but Ignac kept on marching.

When the Germans realized that winter and hunger were making their own "selection" on the march as to who should die and who should live, they were upset. As sons of the superior race they felt deprived of their innate right to command life and death. So they decided to assist the elements in their deadly chores. Those who marched with a steady step were commanded to carry on their wearybacks the staggerers and the stumblers. Now inmates were returning their souls to their Maker in pairs - one inmate facing the white barren land, the other gaping with open frozen mouth at the gray skies above. But Ignac continued his march. It was as if his legs were separate from his aching back and its human cargo.

After two weeks, a few thousand marchers reached their final destination - the infamous concentration camp of Mauthausen. Ignac was among them. Some time later at Mauthausen a selection took place. Stripped to their waists, the newly arrived inmates were lined up on the roll call grounds. Protruding rib cages and stomachs sunken into triangular hollow pits lined the roll-call square. A young S.S. officer began to select his prey.

Ignac followed intently each movement of the S.S. man. He tried to figure out the criteria for life and death. He noticed that the man quickly bypassed the more healthy-looking inmates and lingered for a moment near the emaciated ones, just long enough to record their number, never raising his eyes above the inmate's sunken chest. Ignac understood that skilled labourers were not among the privileged. The only passport to life was a few pounds of flesh on one's body, and he was a mere bundle of bones. He knew that he stood no chance of passing this selection. He would be taken away with the other 'muselman,' fuel for the chimneys.

An idea flashed in his mind. His lips started to move and frantically he began to whisper something. With each movement of his lips his heart beat faster and faster! Color was returning to his pale lips and determination filled his eyes. He looked as if he were reciting an ancient rite of life, a magic spell that could change darkness into light, and beasts into men. The S.S. man stood in front of him. He never looked at Ignac's face, as though his eyes were drowned in the hollow pit that once was Ignac's stomach. "Your number," the German hissed between his clenched teeth. Ignac recited a number with the same self-assurance and ease with which one responds to one's own name. The Nazi recorded it on his list and moved on to pick his next victim. Hours later all were dismissed.

At the edge of the roll call grounds, trucks were lined up. Zeilappel was called again. The inmates, dressed in the concentration camp uniform, line up again in the huge square. Ignac saw his life and death hanging in balance, for the number he had given earlier that morning to the S.S. man was not his present number, 7327, but one of his numbers from a previous camp.

The same S.S. man from the morning roll call appeared with list in hand. Each time he called out a number, an unfortunate man would step out from the line and march to an assigned section near the waiting trucks. Some ran, others walked as if in a trance. Still others lingered for a while, knowing that they were taking their last steps on blood-stained earth.

A number was called. No one responded. The S.S. officer repeated the number again; no one stepped forward. With each repetition of the number, the anger in the officer's voice mounted until it became a raging scream. But to no avail: not a single inmate took a step. The S.S. man began to run from one man to another staring into their gray faces, checking their numbers. He stopped in front of Ignac. His bloodthirsty eyes searched for his elusive prey. "Your number!" the German screamed. Ignac looked straight into his eyes and calmly said, "7327." The S.S. man moved on and continued to search in vain for the missing number. No number on the roll call square matched the one on his morning list.

The camp commander apeared. A paralyzing fear came over the inmates. Though new at Mauthausen, they had heard about the cruelty of Franz Ziereis. The camp commander whispered something to the young S.S. officer. Only Ignac knew what the experienced henchman of Mauthausen was telling the young S.S. man, that the number given to him that morning was not a Mauthausen number.

Roll call ended. The lucky ones returned to their barracks. The trucks pulled out, the engines letting out a strange, weeping shriek. Roll call square was empty, except for the smoke that trailed behind the departing trucks.

That night, Ignac dreamed that World War II had not yet begun. He was a young yeshiva student, going to visit his grandfather, the Dolha Rabbi, Rabbi Asher Zelig Grunsweig. It was Sabbath afternoon at dusk. The little house was filled with twilight shadows and the special, tranquil Sabbath spirit permeated each corner of the sparkling room. It was time to eat the third Sabbath meal. While Grandmother set the table, he and Grandfather washed their hands from the special big copper cup with two huge handles. Grandfather made the blessing over the two loaves of hallah. It was warm in Grandfather's home. They were singing zemirot, traditional Sabbath songs. Grandfather was stressing the importance of the third meal, telling him that it is the most spiritual and mystical of the Sabbath meals. He who becomes imbued with its spirit will be spared the battles of Gog and Magog. "Remember what our sages say, 'Whoever observes the three Sabbath meals will be saved from the suffering to precede the coming of the Messiah, the rule of Purgatory.'" Grandfather was caressing Ignac's head while he spoke to him in his good and gentle voice. "You will grow up, my child, and will survive the suffering that precedes the coming of the Messiah and the rule of Gehinnom (Purgatory). BUt you must always attempt to observe the third Sabbath meal, for its merit will protect you."

Ignac woke up, still feeling his grandfather's warm hands upon his shaven head, hearing that reassuring voice and tasting the aroma of Grandmother's Sabbath hallah. Ignac did not permit himself the luxury of dwelling too long on his pleasant dreams. Camp reality demanded every iota of his strength and concentration. But the dream did not allow itself to be forgotten. itdid not fade away into the deadly realities of Mauthausen. Night after night he kept dreaming the same dream, until his Grandfather's house became a reality and Mauthausen a nightmare.

From his meager rationed food, his starvation diet, Ignac began to hide his crumbs of bread, a crumb of bread per day. He concealed it well inside his concentration camp uniform so that no one could steal it from him even when he was asleep. Despite the terrible, constant hunger pangs, Ignac did not touch the crumbs of bread. Even when he felt that hunger was going to triumph over life, he would not eat his precious crumbs.

On Sabbath, at dusk after a long day of backbreaking slave labor, Ignac would manage to wash his hands, seek a corner where he would not attract too much attention, and celebrate his third Sabbath "meal." Slowly, he would chew his six crumbs of bread, tasting in them his grandmother's delicacies, hearing his grandfather's soothing melodious voice singing the zemirot.

The peace and tranquility of the Sabbath would be upon him and the hell of Mauthausen would be overpowered by the Sabbath bliss.

On May 6, 1945, Mauthausen was liberated by the Americans, the 21st Armored Infantry Battalion and Combat Command B of the 11th Armored Division of the Third Army. Ignac was among the lucky inmates to be liberated that day.

(Based on an interview by Leila Grunsweig with Ignac Grunsweig in December 1978. From: Yaffa Eliach, Hassidic Tales of the Holocaust, New York, 1982 pages 172-176)

Yehoshua Danziger – Shabbat in the Labour Camp (Tiszalok, Hungary)

Yitzchak Bennet – The Melave Malka (Post Shabbat) Meal (Szaszregen, Transylvania)

All of My Bones Will Say "Holy Shabbat"

All of My Bones Will Say "Holy Shabbat"

At the end of summer 5704 (1944), about ten thousand Jews worked hard constructing an airport near Budapest, working seven days a week, including on Shabbat.

As the month of Elul approached, the sun began to set earlier, and thus Shabbat started before the workday was completed. David Leib Schwartz did not forget that Shabbat until his last day. Towards the end of work, with the onset of Shabbat, he decided that he should leave the hoe in the open field and not carry it to the camp, since forests and the wilderness do not count as public areas (in which carrying on Shabbat is permitted). And so he returned to the camp. "Where's the hoe?" He was asked by the guard at the camp gate. "My stomach hurt," he replied. The gentile understood that this was a way of evading answering the question, and even if his stomach really hurt, such excuses were not acceptable… "You are playing games again, I will pay you back tomorrow, now go inside" he said, everyone breathed a sigh of relief.

Since the young man, David Leib, obtained an exemption from working on Shabbat, he understood that the punishment would surely be in relation to this exemption. He guessed correctly, this was the decision of the chief officer. David Leib was determined to find a solution to the problem. On Saturday morning he didn't show up for work; the soldiers were in a horrible mood. "The young man Schwartz is gone!" they shouted loudly. "Where did he go?!" The chief officer started screaming at them, and gave the order to go to work. "I'll take care of him," he announced. They searched for him for about two hours, until suddenly someone discovered him hiding in the officers' bathroom. The chief officer ran to the scene and went inside. What happened inside, no one knew. (Later, David Leib revealed in a rare moment: "I once hid in the camp in the bathroom. When the evil one entered in a fit of rage, I immediately opened my shirt near my heart and shouted 'shoot!'"). They took him outside, the chief officer's eyes full of anger, and in a furious voice he shouted "Go to work immediately!" David Leib insisted and shouted in his anger "Today is the holy Shabbat, I am not going!" The Hungarian chief commander aimed his weapon at Rabbi David Leib's temple. But after a moment he noticed David Leib's brother approaching. He lowered his weapon and said "Your brother will avenge your blood…" for some reason his heart softened. And then… the blows came from all sides - the gun barrel, hands, boots. David Leib's head shook with each blow. The soldier expected that the young man would quickly understand the meaning of the blows and set off to work, but David Leib remained in place. The gentile's anger grew and he raised his hand to strike again, "Then," according to his brother Rabbi Meir Schwartz, "my brother David Leib said in a voice, 'I'm going,' and started walking." The soldier commanded "Hurry up, go to the workplace on foot, and take the hoe to work with. The swollen face did not cross his mind, he pondered "How will I carry the hoe on my shoulders when today is Shabbat?" and he immediately shouted again: "No, no." The soldier was shocked by the young man's courage, he was triggered a second time and started to rage. David Leib did not do anything and wept tears of joy: "Whoever sanctifies Shabbat as befits it...his award is very great in accordance with his actions" (lyrics from a song sang on Shabbat eve). "No! No! Shabbat!", David Leib groaned from the blows. The soldier hit his legs and stomach, he kicked him brutally. David Leib felt weak, and pain hammered in his small head. He tried to raise his voice, but could not. "I'll do it, there's no choice, this is a matter of life and death!" David Leib raised the hoe on his rebellious shoulder and stood up, it was difficult for him to walk with the forbidden load on his shoulder. The excerpt from Shulchan Aruch (Code of Jewish Law) flashed before his red eyes: "Anything that is taken out, which is not a piece of jewelry and is not clothing, and they carry it in the usual way that it is taken out, is liable," and also the famous Magen Avraham (Rabbi Avraham Gombiner) said "Know everything where it is said that he is liable, if he did it intentionally he is liable, and by mistake, i.e. he forgot that it was Shabbat, etc. is 'obligated to bring a sin offering,'" oy, and the Machatzit HaShekel (Rabbi Shmuel Loew) writes what is written regarding the laws with the punishment of stoning. What will be? He was in pain. Shabbat beckoned his suffering… but David Leib had to start walking. And he walked… three steps, and stopped. He lowered the hoe to the ground, and again raised it on the shoulder for another three steps, lowered and raised it again. In doing so, he wanted to be saved from the Torah prohibition of carrying something for more than 4 amot (a biblical unit of measurement), but he was not spared the wrath of the gentile soldier's arm. The gentile did not understand why he was stopping every few steps. His mouth foamed with anger, "This little one will abuse me?!" He took a whip, and struck. David Leib continued to walk. And after three steps he put the hoe down and immediately picked it up and continued. The gentile raged. Every time the hoe came off his shoulder, another blow hit his back.

The Shabbat sun sent its rays, and tears flooded the young man's eyes, the trees did not hide them. His tears were clearly visible, the earth absorbed them, and Shabbat flaunted them. From time to time, the cries of David Leib, a graduate of the Szerdahely Yeshiva were heard, and were swallowed up again among the trees. Oy! Oy! The gentile rested from time to time, but Rabbi David Leib did not take pity on the soldier and continued to lower the hoe every three steps. The gentile on the other hand decided to make an effort and hit him again and again. As far as David Leib's brother was able to look from a distance, he saw that David Leib was still putting the hoe down, even though he was getting hit every time he did so.

They arrived at the workplace. The gentile allowed him to rest on the ground and recover his strength, and then gave him to the German soldiers responsible for the work. The work in which he was involved did not involve a biblical prohibition of desecrating Shabbat.

When he returned from work, Shabbat was already done, the evening spread its wings to distinguish between the holy and the profane. All over his body, his bones ached and his skin burned. As David Leib he entered the barrack, he sat down on the straw floor, and his tormented body shook with pain. These pains accompanied him until the end of his days, and they will also accompany him later, but the sanctity of the Sabbath was not violated!

(With the Strength of a Hand: Chapters of Strength from the Life of the Chassid and Righteous Man, Rabbi David Yehuda [Leib] Schwartz, Published by the Daat Torah Institute, Jerusalem 5762/2002, Pages 18-22)

Shlomo Wakstok – Keeping Shabbat in Siberia (Kalisz, Poland)

Aharon Fromer – Shabbat and Holidays (Lodz, Poland)

Jews from Krakow, Galicia, returning from Shabbat prayers in synagogue, wearing their streimels and kapotehs (chassidic hat and robe)

Yitzchak Meir Shpernowitz – Shabbat in Siberia (Ostrow Ozowiec, Poland)

Poria Sokal – Keeping What is Possible/Shabbat in the Camp (Warsaw, Poland)

Shaleshudis (The 3rd Shabbat Meal) in the Lodz Ghetto

Shaleshudis (The 3rd Shabbat Meal) in the Lodz Ghetto

The terrible hunger in the ghetto had the power to take away men's natural will to live. Many were broken due to hunger, and everything threw them off balance. The whole existence of the unfortunate ones revolved only on one matter: food, food and food.

This was not the case for my brother and his chasidic friends. They did not submit to the dictates of the time, and absolutely refused to change their principles. According to their perception, saving their bodies was secondary, saving their souls was at the top of the priority list. They studied Torah continuously and followed the ways of Chasidism. They satisfied their hunger in the common kitchen which was founded on the meager food they received in the ghetto. Their meals were held together while listening to Torah lectures and chasidic tunes. They were neither broken nor afraid. Hope filled their whole being and overcame everything else.

For the Shaleshudis held at our house, each of them brought their meager food. Tables and benches were set up, and my mother prepared a number of impromptu "foods". I thought to myself that the boys will steal the food!!! To my surprise, they settled down comfortably and began to sing and give over Torah lectures. Only at the end of their passionate chassidic dance would they go to the meal...

I looked into their glowing eyes, and then I realized that in the difficult conditions of suffering and pain, fear and hunger that the Germans created with the intention of breaking the Jewish spirit, these chasidic individuals expressed the greatest rebellion against the German enemy.

(Chana Eibeshitz - Eilenberg, Woman in the Holocaust)

Aharon Fromer – Shabbat in the Labour Camp (Lodz, Poland)

Jews receiving Shabbat in the Zalsheim DP camp

Meir Blum – “Remember the Shabbat Day…”

Receiving Shabbat in the Train

Receiving Shabbat in the Train

On the way to the Westerbork camp, Tammuz 5703 (Summer 1943)

The train raced towards the Westerbork camp. It was on Shabbat eve in the early evening, when we sat anxiously and in a tense silence awaiting our future. German soldiers stood by us. No one spoke, until father broke the silence and confidently said: "It's time to accept the Sabbath!" We prayed and father blessed the bread. We ate a little, and even blessed the Grace After Meals with a "Zimun" (extra introductory prayer when three or more men are present). Father's kiddush (blessing over wine) on Shabbat night, on the train, in the shadow of death in the form of the German soldiers, will remain a lifelong lesson for us.

(Yona Emmanuel, It Will Be Told to Generations)

Menachem Mendel Brickman – The Prayer for Receiving Shabbat, upon Liberation (Pabianice, Poland)

Survivors during Shabbat Prayers

Yocheved Kahan (Lewenberg) – A Girl in Hiding in Holland (Utrecht, Holland)

Shabbat Candles in Auschwitz

Shabbat Candles in Auschwitz

When we arrived there on January 18th, 1943, we were placed into barracks in Birkenau, which had served as horse stables in the past. We received wooden bunks for sleeping. One of the first things that we did, myself and the friends who arrived with me, was to find people we knew who were still alive, prisoners wandering around Auschwitz. And we found them.

One of the first things we requested from them were two wicks. On Friday night, we gathered on the top bunk in our barrack. We were at the time between 10 and 12 girls. We didn't stay there long. In the complete darkness, with no proper floor and sanitary conditions in Auschwitz at the time, we lit the candles and began to quietly sing Shabbat songs. We were blinded by the light of the candles, and we didn't know what was going on around us. After a short pause we heard muffled crying all around, above all, from the bunks that surrounded us. First the crying startled us, shocked us. It turned out that from all places - and it was possible to move from bunk to bunk - Jewish women who had been sitting there for months, even years, gathered around us on the neighboring bunks, listening to the singing. There were a few who came down and asked that they be allowed to bless the candles.

It was a shocking first case. Then those in the block got used to lighting candles every Shabbat eve. We had no bread, sometimes there was nothing to drink, but we somehow got the candles.

(Rivka Cooper, excerpt from her testimony at the Eichmann Trial)

Yechiel Gerentstein – Partisan in the Forest (Lublin, Poland)

A Jewish family on Shabbat in the Warsaw Ghetto

Yehoshua Eibeshitz – Self-Sacrifice for Keeping Shabbat (Wielun, Poland)

Kiddush

Kiddush

In our cattle car (on our way from the Theresienstadt Ghetto to the Auschwitz death camp), there were 50 men and women. Each person who entered the cattle car held the packages that they were permitted to take with them. The car was very packed, and with difficulty we found a place to sit. The cars were intended for shipping cattle and thus there were no benches or windows. The air and light penetrated through a small porthole near the roof of the car. There were many old people, babies, and sick among us, who in these conditions suffered greatly.

The first night of the trip passed without the possibility of sleeping even for an hour. Then the second day and night arrived - the Shabbat were the Torah portion about Mount Sinai is read.

On Shabbat, every Jew is in a sense a king, because that is how the Shabbat Queen deserves to be received. In honor of Shabbat, candles are lit in every Jewish home, and in their bright light the Shabbat meal is eaten and song are joyfully sang which express great longing for the Creator of the world who commanded us to sanctify this holy day. And who are we to accept the honorable queen at such a time? Wretched creatures being transported in an wagon meant for animals, hungry and thirsty, tired and torn, enveloped in the darkness of the night without a ray of light. Are we even allowed to accept Shabbat? And perhaps it is vice versa. Perhaps our queen is proud, that in spite of everything we are loyal to her and we do not forget her majesty over us even in such miserable conditions. Because who knows how to appreciate the oppressed and wretched soul that keeps faith in its creator even at this time.

Father makes Kiddush over a dry slice of bread, which is also used as the Shabbat meal, with a sip of water. And so we also observe the mitzvot of enjoying Shabbat. Even then, father remembered Shabbat. And I am sure that the Creator looked at us together with his Heavenly entourage (angels) and said to them: "Look at my children who remember me and my holy Shabbat even when they are imprisoned in total darkness inside a cattle car, in hell on earth.

At the same time, the Heavenly entourage answered Him: "You are One and Your Name is One and who is like Your people, like Israel, one nation in the world."

(Rabbi Sinai Adler, Thy Rod and Thy Staff)

Esther Dawidowitz – Shabbat Candles in the Camp (Hungary)

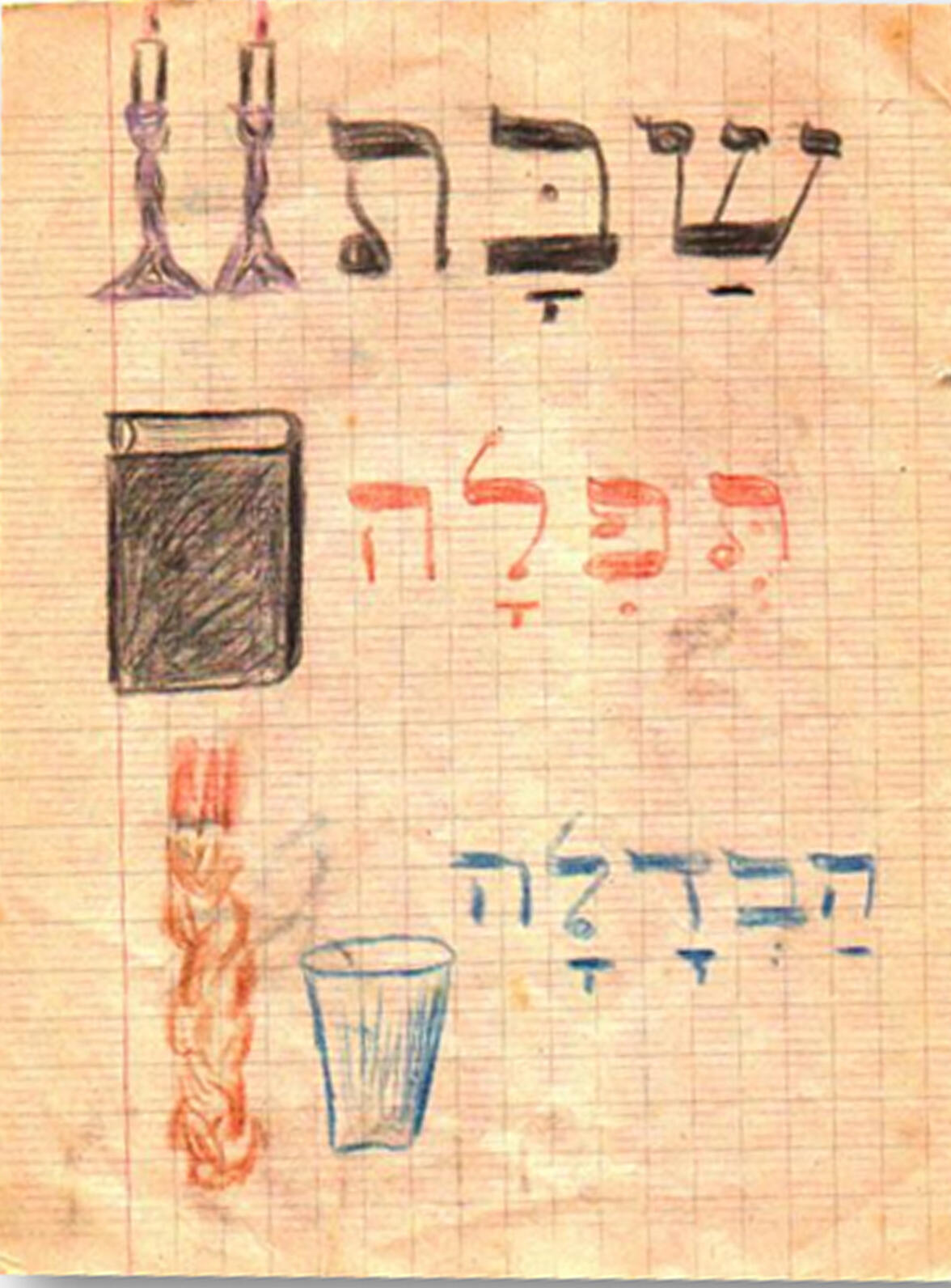

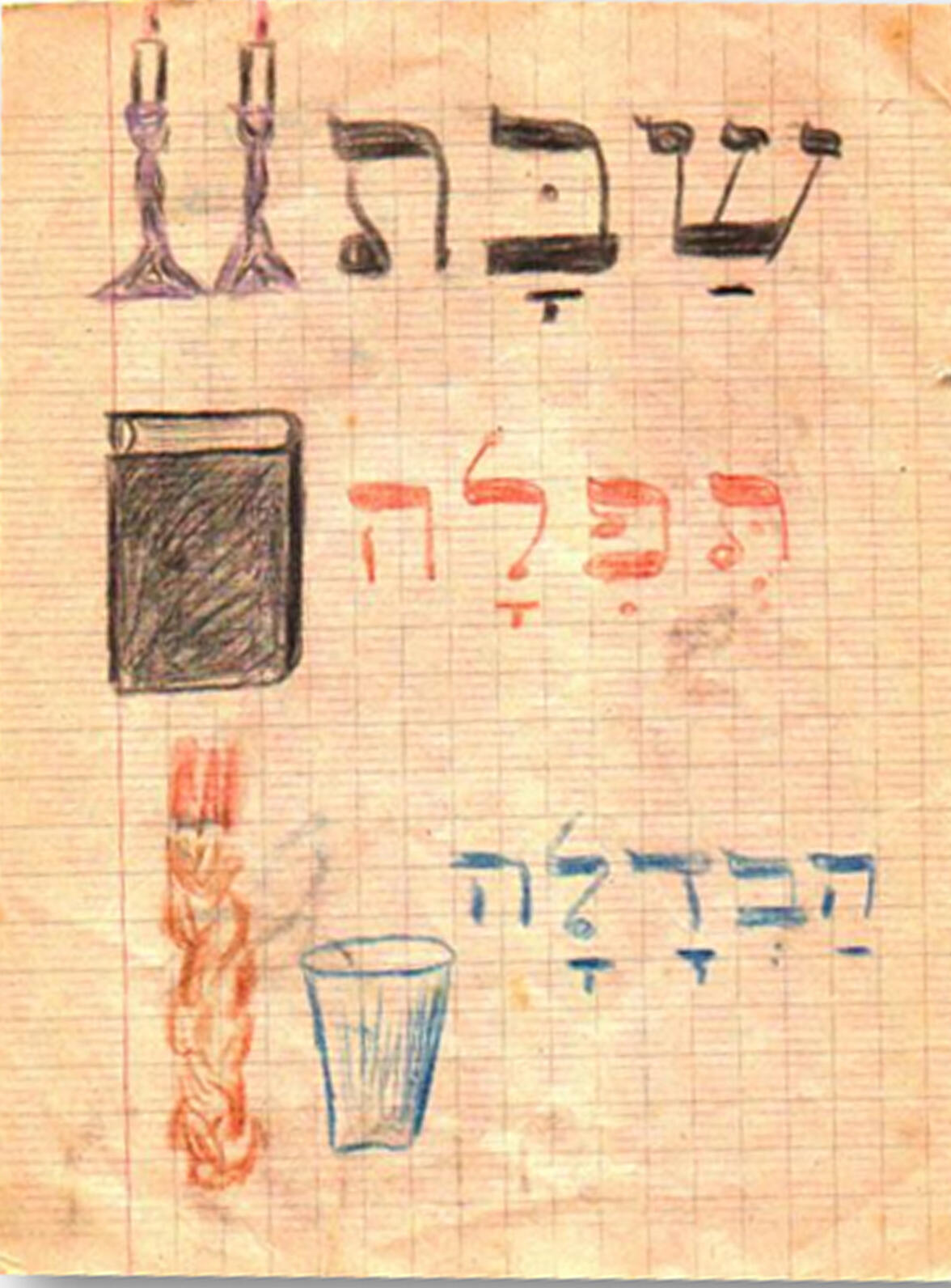

Felix Goldschmidt (France), The Laws of Shabbat in Drawings for Children in Hiding

Esther Borstein – Shabbat Night in Auschwitz

The Trial on Shabbat Night

The Trial on Shabbat Night

The Tisha B'Av fast day in the year 5704 (1944) in Bergen-Belsen. This was the first time that all of the camp inmates received a punishment together. That day there was no food, not for adults, nor for women, nor for the elderly, and nor for the children. The reason for the punishment: The Germans discovered that someone burnt a mattress, as the mattress was full of lice. This was an unforgiveable sin, a serious infraction and therefore a punishment was imposed on all the inhabitants of the camp from young to old. Tisha B'Av.

My mother cooked some porridge without milk for my younger sister Batya, who was four years old. She cooked it without an oven nor oil, with a little straw and a lot of work. At the last moment, two of the Jewish guards in the camp caught her. There will be a trial.

And so a trial was held, run by the administration of the camp. In addition to the punishments that the Germans imposed, the Jewish leaders in the camp also were forced to punish the perpetrators. An internal trial was held for this purpose. The Germans enjoyed watching how Jews punished their brethren. They "played on her case."

My mother's trial was set for Friday evening, Shabbat Nachamu (the Shabbat after the Tisha B'Av fast day) 5704 (1944). In general, trials like this were held often, and included a Jewish prosecutor, witnesses, the statement of the accused, the defense of the defense attorney, and the judges' verdict. They were all Jews, the prisoners of the camp. But mother's trial lasted only a short time.

The verdict: denial of bread rations for two days. Mother waived her right to deny some of the excessive accusations and even waived the participation of the aforementioned defense attorney to request a reduced sentence for the offense of cooking for a four-year-old toddler.

In Bergen-Belsen there men's and women's camps were not entirely separeted and thus it was possible for men and women to meet. We sat on Shabbat night and waited for mother to return from the court. When she told me about the verdict, I asked her why the trial was so short and why she didn't exercise her right to deny at least some of the charges. Why didn't she say that on that day they didn't distribute any food and therefore she cooked something for her little daughter? My mother didn't answer. I saw that she was very emotional. I dared to asked her one more time, and my mother answered: "There were not only judges, a prosecutor, and a defense attorney there. There was also Jew sitting there who wrote out the minutes of the trial. Every word I said there was immediately written down by a Jew, and on Shabbat night! That's why I kept quiet. It's better to starve a little more, than to cause a Jew to write on Saturday!"

(Yona Emmanuel, It Will Be Told to Generations)

Faiga Leah Bolak – Assistance and Aid in the Lodz Ghetto (Lodz, Poland)

Feiga Leah Bolak – Assistance and Aid in the Lodz Ghetto (Lodz, Poland)

Zimmel Rotstein – The Invasion of Poland (Poland)

Shabbat Candles in the Labour Camp

Shabbat Candles in the Labour Camp

Allendorf, Germany. Grey skies, blowing winds, lonely birds, bare trees that have lost their leaves, a gloomy and dismal autumn. The autumn wind tangled the leaves in the pieces of paper and everything else in its path, swept them left and right, backwards and forwards, as if told to go out with them in a stormy dance.

This gloomy appearance was not there to warm the broken hearts of the Jewish female prisoners in the weapons factory. About a thousand Jewish women worked in the factory and they were strictly supervised. The SS commanding officer frequently checked the work and each visit usually resulted in heavy punishments.

A short piece of information that was whispered in my ear on one of the sad and gray days warmed my heart.

"I have candles in my hand, candles in honor of Shabbat, would you like to light them too, Miriam?"

I looked at her strangely.

"Can't you believe? Shabbat candles! I found fat in the department where I work, and I melted it into these boxes, and here I have candles." A spark ignites, like a wick of fire. Knowing this was powerful. Lighting candles in your souls, candles, candles of Shabbat in the midst of the days of darkness and judgment in the heart of the threatening gloom, candles of the holy Shabbat will be lit… At that moment I forgot about the SS commanding officer, it is difficult to explain, even with the sight of the rifle's barrel aimed at me. In short, I forgot where I was, for it was in the words that I heard a kind of supreme power that kindled a hidden flame within me, and its tongues of fire made the factory, its occupants, and everything in it disappear from my sight.

"Yes" I answered firmly

"And you are not afraid?"

"Afraid of what?"

"From the whip, from the rifle, from the soldier, from the furnace, from the gas chamber, from... and"

"From our heavenly Father I will fear, I interrupted her flow, I seek to fulfill my duty as a daughter of Israel."

That evening my friend stole two candles for me, two simple candles. At first glance it could be seen that it was done by an unbeliever, and cylindrical bulbs were inserted into it. My heart accepted them. At that time, it was as if I had found my lost child who had been kidnapped from me for many days or as if they had returned to my soul the part that had been evily and maliciously cut off.

What power do these simple candles have that they lit up my heart? I didn't know how to explain this feeling, but I felt as if the souls of the righteous of all generations were bound strongly in the candles… Perhaps I saw this bond while my mother's face was covered and I felt how my mother's merit was illuminating my dying heart.

I concealed them on me, in a worn bundle of rags that sometimes had the privilege of storing bread that I had saved for a patient, but this time its importance increased. I had to wait two more days for the holy Shabbat to come, two days of bleakness and gloom, two more days of tribulations, but it seemed to me as if we were sanctified this time with the holiness a joyous soul longing and for the coming of the holy Shabbat.

Friday arrived. In my room were 14 Jewish girls who had finished a grueling day's work and were getting ready to welcome the Shabbat Queen. No furniture was found in our room except for an old chest, on that chest I placed my candles. I asked all my friends to partake in the merit of reciting "amen" to my blessing.

The time for lighting the candles approached. It was a beautiful time before sunset. The west was already lit up with a crimson reddish hue, that day the sight was twice as beautiful as the shaky centre of the eye of the sun about to set in sight of our room which decorated in honor of Shabbat. The ray of light that flickered in the room lingered for a brief moment and lay to rest on the table where the candles stood. The small candles were suddenly illuminated by a streak of golden light that gave them an undeniably noble appearance, a vibration went through my heart, the ray of sun also shook and wandered…

13 pairs of eyes were fixed on me at that time, some of them were evidently afraid lest… lest the gentiles come to this place of ours…. but everyone's eyes shone… shone with a fire that burned in the hearts of us all. Recognition was amongst these pure daughters of Israel, such is how attached their souls were to the lighting of the candles… they were ready for anything. "Like my mother when she lit candles" one whispered and the others shook their heads in agreement for the tears choked in their throats.

I lit the candles.

I moved my hands over the candles and was about to cover my eyes when suddenly...

The sound of rough footsteps came from the corridor. We all knew the sound of the footsteps; we did not deceive ourselves and we knew very well that these were the footsteps of the SS commanding officer. The hearts of my friends seemed to have stopped… I shielded my eyes and blessed "Blessed are You… Who sanctified us… to light Shabbat candles." And I continued to cover my eyes and did not remove my hands. At that moment I asked silently "Master of the world, it is visible and known before you that I did not do this in my honor but in your honor… in honor of the holy Shabbat…that they may know and remember everything… 'because six In days G-d made the Heavens and the earth, and on the seventh day was Shabbat and He rested.'"

The commanding officer had already slammed open the door. Before her eyes the spectacle unfolded in all its glory. There was silence in the room. She didn't dare to interrupt…all the time I was covering my eyes, she stood and stood and wondered…

When I lowered my hand, I heard her order: "Go out to the waiting vehicle."

Everyone huried to fulfill her order, and she went out after them.

I was left alone in the room. I looked at the candles; "Was it because I lit the candles that all my friends were taken somewhere?"

The candles lit up my lips that were muttering a prayer, I felt as if the souls of the righteous women from all generations were being brought by their wings to the throne of glory (G-d's metaphorical throne) and were laying before G-d.

And then I knew, they would not be harmed due to the lighting of the pure Shabbat candles...

I went out after my friend, from far I saw the parked car. I felt myself walking towards it. When I reached it, I found my friends unloading bread from it. I saw their calm faces when they replied to me, "The officer ordered us to move the bread to the kitchen."

Phrases of praise and thanksgiving flowed from their mouths. Later I found myself talking and saying: "Blessed is He Who performed a miracle for me in this place." Messengers of mitzvot (Torah commandments) are not damaged…

I raised my eyes to the Heavens. The sun was already setting. A streak of light flashed for a moment in the west like a towering flame, as if it wanted to shine and testify to all the inhabitants of the world about the miracle G-d did in this place...He finished his job and disappeared.

The sun set. The Shabbat Queen descended upon the world.

(M. Weinstock - Zachor, Part 8, Page 96)

Rabbi Shlomo Papenheim – A Quorum of Jews in Clifton, England (Germany)

A woman lighting Shabbat candles in a refugee shelter in the Warsaw Ghetto

Avraham Gershon Fonfeder – Shabbat Songs from My Father’s Home (Budapest, Hungary)