Rabbi Yaakov Rosenfeld – Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

On one of the nights of the Nine Days (preceding the Tisha B’Av fast day), we gathered at the home of Rabbi Hanoch Henich Zeibert, the former mayor of Bnei Brak, to listen to his memories of his father z”l and grandfather z”l, the genius and righteous chassid, Rabbi Leibel Kutner z”l.

We sat in his home, a group from several denominations and circles who came together under these circumstances; chassidim from different chassidic groups, Litvish Jews (literally Lithuanians, but refers to Charedi Jews), sephardim, and some of Rabbi Hanoch’s family.

The meeting that took place at the initiative of Ganzach Kiddush Hashem and Zikaron BaSalon (Memory in the Living Room) made a strong impression on us, far beyond what we could have imagined in advance.

A questioner can ask, what new information about the Holocaust can be learned when all its angles have already been examined? And in general, what is the purpose of these talks, and to where are they supposed to bring us?

The answer is that the Holocaust, a contemporary horror, still has hundreds of thousands of its survivors living, whose memories and records are still engraved in the soul of the nation, and these have indeed been recounted and reviewed and described in almost all languages in countless books and publications and recordings and films, etc., but the Jewish, internal story, has almost not been told at all, as most of our Holocaust survivors saw no reason to tell these stories.

At this event, one of the stories told by the host Rabbi Hanoch was about the chasid Rabbi Leibel Kutner.

When Rabbi Leibel arrived after the Holocaust to the “Beit Israel” Rebbe, the same Rabbi Leibel, who had formerly been successful, a businessman, and the head of a family…the Rebbe asked him: Leibel, do you have any complaints? And the chassid, Leibel, answered: I don’t have any and I never had any.

They had no complaints; They never were in a “state.” They did not want to tell about things as they were lest the things arouse difficulty, and again, the fact that they themselves kept the faith and managed to start over despite everything, what is the point of telling about it, and even more, what novelty is there in it…

Millions of horror stories took place in the Holocaust, but the horrors of the Holocaust are not stories, just as its events are not history in the usual sense; history that is read about and studied. The Holocaust is a terrible wound in the heart of the nation, a mortal blow that will never heal.

The memory of the Holocaust is oppressive and burning. It has no comforter; it has no explanation, and therefore, Jews over the years did not like to talk about what happened to them in the days of darkness and persecution. Many of the survivors of the atrocity did not talk about it or tell about it, and even tried, if possible, not to reflect on it.

But when their children and students gather, and try to remember the few things that have come out of them by mistake over the years, and reflect on them, then sheets of heavenly, angelic life are spread before them, a life of holy and pure virtues, like the shining light of the sky, a life of streams of faith and joy that have never stopped flowing and their freshness has dulled, so we must keep these memories alive and pass them on.

It behooves us, and our generation, to know where we came from and what is the source of our strength.

In this thread we will present some of the memories of Rabbi Hanoch Zeibert , as they were said in this gathering.

The only offspring

My grandfather, my mother’s father, Rabbi Moshe Ershter, once saw wrongdoers beating a Jew on the city street. The view touched his heart and at that moment he decided tht he wanted to immigrate to the Land of Israel. I do not want to be in a place where Jews are beaten and humiliated just because they are Jews.

He married my grandmother, also a daughter of wealthy people, the Davidowitz family, and together they immigrated to Israel and this is where my mother was born.

The plan was, as well as it being the desire of the family members from all sides, for the young couple to return to Poland, to live with the affluent, supportive parents, but my grandfather announced: since I am already in Israel, I am not leaving the country.

They did not return to Poland, then the war broke out, and of all the extended families – my grandparents were the only remaining offspring.

What does G-d want from me?

Rabbi Zeibert told wonderful stories about his ancestors, from the first group of chassidim, whose entire being was Torah, chassidism, kindness, and mercy. The Tractate “Midot” (good manners and character traits) was common on their tongues and written on the tablet of their hearts.

Rabbi Leibel Kutner, one of the family members, a legend, was spoken about by his step-grandson, who grew up in his shadow and drank from his well, which opened and started to flow. Rabbi Leibel Kutner was a role model of the Zeibert family, a glorious follower of Gerrer chassidsm, to which G-d encouraged the flowers of the chasidim to adhere.

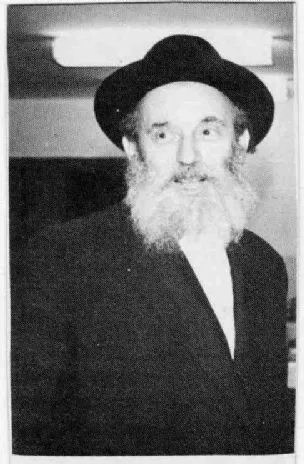

Rabbi Leibel Kutner

Before the destruction, Rabbi Leibel was at the forefront, a wealthy man, the father of eight children, and a man of kindness and action in all his spirit and zeal. When the Rebbe, the Imrei Emet, ordered schools to be opened in every site, since there was no suitable place in his city to open the Bais Yaakov school, Rabbi Leibel closed his shtiebel (small synagogue), which was known as the “Sharpeh Shtiebel”, dispersed his friends to other shtiebels in that city, and in the place of his shitebel, he opened a Bais Yaakov school because that was the Rebbe’s will.

In all the journeys of his life, in all the nooks and crannies he had been to over the years, Rabbi Leibel always thought of one thing: what does God want from me now? He had no time to observe and complain. At this time it would have been better for him to think about G-d’s greatness and his possibilities to worship G-d with heart and soul, whether it was by studying Torah or fulfilling a mitzvah, or by helping and aiding a single Jewish soul who longed to be listened to, for a kind word, for material help, or for good advice.

During the war, during the period when Rabbi Leibel Kutner stayed with Rabbi Leibel Goldberg, the latter was ill with typhus. The condition of the host was not good, and Rabbi Leibel Kutner did much to elevate and strengthen him. He later said: “In those days, when I thought of my wife and children, I told myself that they are most likely no longer alive, but in the presence of Rabbi Leibel Goldberg and his family, I did not let out a single sigh from my heart. I had one goal in front of me, to make him and his family happy. Only when I was alone, far away from the eyes of Rabbi Leibel and his family, I allowed myself to hug God in tears.”

What did Rabbi Leibel Kutner, a wealthy and respectable man, father of eight children, who remained alone, “empty of all good” cry about? In fact, for what did he NOT cry about…and there was there any lack of things for him to not cry about?

But no.

“When I left their house, I would burst into tears and say to G-d, I am asking you to help me so that I will never have complaints against you”…

I remember Rabbi Leibel in his old age, thirsty young people surrounded him and wanted to hear more and more. And Rabbi Leibel Kutner would tell them:

“A Jew who studies 12 hours a day, prays for a long time, and observes mitzvot, has nothing to be proud of. And what is his duty in his world, not to study 12 hours a day and pray at length and observe mitzvot?”

“What did give me, for example me, satisfaction for the rest of my life? When I gave to someone else. When I helped, when I extended a hand, palm, ear, and heart.”

“That’s what I used to do in those days, and also after them.”

This is what is indeed engraved on his gravestone:

“He was blessed to raise orphans and make sacrifices for the Torah. Out of love and compassion.”

After the war, Rabbi Leibel would go around amongst the Holocaust survivors and comfort them, and talk to their hearts. Many of them saw themselves as his children, grandchildren, and students. He would raise them up from the dirt. He was everything to them. He shone light in the darkness of their lives. They were all orphans, bereaved parents, lonely and abandoned. He helped them physically, he built them up spiritually. He lit a light of Torah and faith in their hearts. He founded institutions and communities and groups. And after much toil, he was able to board a ship with his students to Cyprus.

It was not quiet in Cyprus either. How many wedding canopies he erected, how many houses he built, how many souls he enlightened and how many broken-hearted he directed and brought cure for their brokenness.

And when the days of exile in Cyprus were over, he and his company sat in a ship that dropped anchor in the port of Haifa on the holy Shabbat, and informed the captains and the people of the settlement who came to take them off: “We are not disembarking on the holy Shabbat. We did not go through all that we went through to desecrate Shabbat here in the Land of Israel.”

And in the days of British rule, the immigrants were at high risk that the English would catch them and throw them back to hell, and that is what the captain threatened them with. And this is what the underground people warned them about. But Rabbi Leibel sat peacefully with his whole group. “You can do what you want. We did not arrive in the Land of Israel after so much sorrow and upheaval to desecrate Shabbat right here.”

Nothing helped. They waited until Saturday evening, did havdala (Shabbat closing ceremony), and then went down to the beach.

I heard from a Jew who was not among Rabbi Leibel’s students. “I was ashamed of them. I saw everyone get off and they stayed. And I was not able to get off. I saw the behavior of Rabbi Leibel and his students and I decided to behave like them. I stayed on the ship until Saturday night.

In the war, he would say, “this is what I kept telling myself: If I will live or not, I don’t know. What G-d wills is what will be, the soul of every living being and the spirit of every human flesh is in His hands.”

“But I must fight for my spirit. They want to take my breath away and I must fight for it until my last breath. This matter is up to me and I will fight to the end. My spirit will not be broken!”

He would say to himself and those around him: “The fact that we are Jews is a reality and we have no way to escape from the law… ‘You (G-d) chose us from all the nations.’ He has already chosen us and we are His, so we should not run away from the confrontation and certainly not surrender to the situation. Rather, we must fight for the image of our G-d.”

Not on bread alone can man live

I heard many things from him about his way of coping in those days.

For example:

“I never walked around the camps or the ghettos with eating utensils (as was the practice of many prisoners at that time, whose plate was always belted to their side so that if they distributed food, they would be immediately ready with the plate). I didn’t see Jewish exaltation or strength in this leadership… When food was distributed, I would go to my room, take the plate, and go to the place of distribution. If I will have some left, this would be good, if there won’t be any – so no.”

“I never put the spoon into the saucer to see how many pieces were inside. (Oh, how the people dreamed of these pieces. They were pieces of life. A soup with little pieces of vegetables or grits – one thing, and a soup “rich” with some grits or vegetables – another thing entirely.) I would put a spoonful on the plate and eat what was there in moderation, with faith that what is due to me will come, and looking for pieces with a spoon – is not honourful for me.”

Survivors told:

Once Rabbi Leibel ran after the bread distributor in the camp. He really ran after him.

He was used to people wooing him. Bread then was the only dream of all the wretched people living there in the ghettos. Bread was their hope and comfort. Songs and poems were composed and written about the “bread.”

But Rabbi Leibel, that’s not what he wanted.

He caught up with him and scolded him: “Why don’t you also bring us water for the washing of hands. People here want to ritually wash their hands before dinner!”

They testified:

Rabbi Leibel never bowed down and did not give in to the wicked either in body or soul. He always stood tall and kept his dignity.

You are a Jew! You can!

There was one sentence that Rabbi Leibel excitedly repeated after telling this wonderous fact:

“One day the SS officer’s hair clipper broke and he was unable to fix it. Even the most talented of his friends did not succeed and he asked all of us if anyone knew how to fix such a machine, and no one knew. He looked at me angrily and said firmly: If you are Jewish, you know how!”

“There, after such an instruction, as we know, there was nothing to argue about, God forbid.”

“He left the machine in my hands and went his way. He wanted it to be fixed by morning.”

“And did I have any idea how the machine works? And how do you fix a machine that doesn’t work?… But I sat down and took the machine apart and put it back together with the hands of a craftsman. I can. I memorized to myself. Because if I am a Jew, even the bitterest gentile knows, I can…”

“I almost succeeded, then, just before the last screw, the machine dropped from my hands and fell apart again. What do you think happend, I broke down? Did it cross your mind? And I’m Jewish, so I can!”

“I sat down again and disassembled, and connected, and finally the machine was fixed.”

“Wonder of wonders!”

“In the morning the Nazi returned and claimed his posession. He himself did not believe that he would receive his item fixed.”

“I waved at his machine and told him, I fixed it for you, but do you think you’ll get it from me for free?”

“I have never given up my honor. I wanted payment.”

“The officer was angry, almost exploded, but asked me what I wanted for the job.”

“Two cigarettes! I answered.”

“The Nazi threw the expensive cigarettes on the ground next to me, took the machine, and left.”

“Since then, I have not forgotten these words: ‘Bist a yid, kenstoo! If you are Jewish, you can!'”

This is how Rabbi Leibel went through the war out of faith, out of joy, and “Yaakov’s genius” (smarts).

He entrusted his life to the One Whose hand it is in to revive and kill, but for his soul, the deposit which was entrusted within him, he guarded it with strength and greatness and never surrendered.

After the war, as mentioned, the survivors had a journey to rise from the depths. He would go the distance with the aim of reviving the broken and breathing life into the dry bones. He was in Poland and Germany, France and Italy; he travelled on trains and to and from their stations. He never rented a hotel room and never used the money he collected for the benefit of the survivors for any personal need. He saw no problem in staying at a train station.

He did not stop working in Israel either.

He was bereft of everything. He lost a wife, lost eight children, and did not merit to rebuild, but he never had any complaints.

“God does not owe me anything, I owe him.”

And only after he married off his students, who were like sons to him, did he remarry my grandmother, and thus I was privileged, as a step-grandson, to grow up in his shadow and absorb from his personality.

How kind hearted he was. When his grandchildren came to his house, he always, made sure when they left to give them things, not only for themselves but for everyone. He did not want there to be a wave of jealousy and hatred, and heartache for something, even a little bit.

Later he said that he received his first “blow” here in Israel. He worked among the survivors with all his might, and built houses for them, and established families, and institutions, and communities and Torah classes, and when he once turned to someone with a request to give a lesson to the survivors of the Holocaust, and the man immediately asked: how much money was involved… he was stunned. Of money?! And that this is the first question of a Jew when he has an opportunity to help others?

The stories about Rabbi Leibel Kutner were numerous, the hours ticked by, and the family members gently asked for something about Rabbi Zeibert’s father, their grandfather Rabbi Shaul Dov Zeibert z”l, born in Krakow and a survivor of the Bochnia camp.

“Remember, do not forget!”

My father was seven years old when he separated from his father. His father had one concern in his heart at all times: that his son, Rabbi Shaul Dov, would sit and study Torah. For this purpose he would pay out of his own pocket and do with less for himself. Today, perhaps we don’t understand the depth of devotion of those days, to give up a mouthful of bread so that the son could sit and study Torah.

As mentioned, at the age of seven he was separated from his father and sent to Hungary. There, his father thought, his son would be safer.

And when they parted, his father said to him: “Remember where you came from. You’re a Jew! And remember your bar mitzvah day.”

In Hungary he had to pretend to be a gentile, but he did not forget that he was Jewish. He was together with his relative Rabbi Moshe Sheinfeld, and they lived a life of devotion. From time to time they snuck into the Jewish side of the town where they lived to observe mitzvot at indescribable personal risk. Later, they saw with their own eyes how the Jews of the city were being deported to Auschwitz, and their sorrow knew no bounds.

Rabbi Moshe Sheinfeld, a young man who was a Ger chassid, did not know what to do during the day. There were refugees, and they could not be at home. He had no job, and what could he do from morning to evening?

My father, as a small child, would sneak out every day to the hall where the Germans showed films from the war, and due to the darkness there, he could spend the day lying on a bench until evening, and then return to his “home”. But Rabbi Moshe Sheinfeld, on the other hand, a Ger chassidic young man, did not agree to enter the place where movies are shown. Even in a life-threatening situation.

And when once he was asked what, for God’s sake, he did with himself for whole days, where he hid, and where he fled, he answered simply:

“There were public toilets close to my house. I would go into one of them and lock myself in for twenty minutes, and get out. For two slots of twenty minutes and leave, like that for the whole day until the heat set.”

“I never thought for a moment of entering a place where movies are shown.”

(And you can think about what movies they showed there… war propaganda movies, and also, he wasn’t obligated to see, and that someone would see his actions in the dark?… a Ger chassidic young man!).

And despite this, we did not forget Your Name

Father didn’t tell, almost didn’t speak. But on one of the few occasions that he did speak, he said that once the gentile in whose house he stayed, and to whom always told that he was vegetarian and vegan and satiated, etc., decided that he had to eat meat. She placed a piece of meat in front of him and forced him to eat. Father put the meat in his mouth and did not swallow. After a while he stood up, he signaled that he should leave for a moment, and went outside and spat the meat out of his mouth. Except for this occasion, nothing that was not kosher, according to him, ever entered his mouth.

On Sukkot he snuck into the Jewish area, entered a sukkah, ate an olive sized portion there and disappeared as soon as he came.

Thus the days passed for him in sorrow and longing, in siege and hardship, but “despite this, we have not forgotten your name”… there was always faith in his heart and fear of Heaven burning in him like fire.

After the liberation, he saw Jews in Tameshwar. He couldn’t believe his eyes. He never dreamed that such Jews still existed in the world. In the year of liberation, he saw the Rebbe of Satmar dancing on Simchat Torah and the sight was a soul-stirring sight, after he no longer believed that he would ever see righteous Jews on earth.

Fasting and a mother’s cry

After the war, my father met his mother.

It is easy to describe the emotion and the tears.

Then his mother said these words to him:

“On the day you entered the yoke of Torah and Mitzvot (his 13th birthday, bar mitzvah), I did not know if you were alive, but I fasted all that day.”

“I prayed to G-d that you would forget that you are Jewish.”

Handmade matza

He spent his first period in Israel in Ponevezh. There he worked in the homes for the elderly where the war survivors were taken in, and became close with the Ponevezher Rebbe.

His soul was greatly effected by his time there. He sat and studied in the presence of the genius (the Ponovezher Rebbe) and rose higher and higher. Much can be said about this period, and I will mention one anecdote.

On the Seder night, the Ponevezher Rebbe sat in the shade. Before the holiday began, Rabbi Leibel’s face brightened and he asked the Rebbe for round matzos, as was the custom of his ancestors. The Ponevezher Rebbe agreed to his request and sent Rabbi Nachman Albaum to bring one kilo of round matza, but then he remembered that all the survivors who were also from Hasidic homes had come, and they also wanted round matza.

He also asked that he be given the option not to eat sheruya (matza that has become wet), and the Ponevezher Rebbe granted him this as well. He ordered a clean plate to be given to everyone and inside it everyone could do what they wanted, but they should not cook broth.

On Seder night, my father meritted to find the afikomen. And what did he ask for in return?

A kapote (a chassidic coat)

The Ponevezher Rebbe no longer agreed to this. He knew that he would not be able to fulfill this wish for all the students of chassidic backgrounds, and giving in to one and not the other did not occur to him.