30 Years Since the Passing of the Author, Sarah Ziskind, Survivor of the Lodz Ghetto

By: Yaakov Rosenfeld, Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

In her book “HaAtara Sheh’Avda” (The Lost Crown), Sarah describes in first person, the distress and suffering, the hunger, and the poverty that she, her family, and friends faced in the Lodz Ghetto. In the book, I read with bated breath about self-sacrifice for values, even in the horrific conditions of the ghetto, and even in the hell of Auschwitz.

The name of the book is derived from the fact that the author’s father was a manufacturer of silver “crowns” (adornments) for tallises (prayer shawls), however the book describes in general the crown of the magnificent and magical Polish Jewry, which was lost…

Sarah was born in 5687 (1926-7) in Lodz to her father Rabbi Asher (Anshel) Kalman Felger and her mother Mindaleh née Biderman.

Sara experienced a happy childhood until she was hit with old age, at the age of 12, in the month of Elul 5699 (1939), when the Nazis occupied her hometown and began the campaign of torture and killing.

Her mother, Mindaleh, died that year from hunger and weakness, and Sarah remained with her father; they strengthened each other and tried with all their might to maintain their human dignity.

Her father, Asher Kalman, suffered greatly in the Lodz Ghetto until his passing on the eve of Passover 5703 (1943). After Sarah buried her father with her own hands, she was deported to Auschwitz, where she received the number 55091, and from there she was sent to other labour camps, which she survival through miracles.

With Divine Providence, today I read part of her book, and I noticed, without my having the slightest idea beforehand, that today is the day of her death. Exactly thirty years ago, on the 13th of Shevat 5754 (1994), Sarah Ziskind, nee Felger, passed away, at the age of 66.

I became emotional; I lit a candle and learn Mishna in the memory of Sarah bat (daughter of) Asher Kalman.

I will copy excerpts from her moving book, from which we will learn about the mitzvahs of honouring one’s parents, from a 13-year-old girl whose world was destroyed by the death of her beloved mother, and the words will be a candle in her memory and an ascention for her soul.

A Medicine Called Vigantol

My father was in bed; now he lost the soup ration he used to get at work. I was at a loss. Desperation ate me up. The severe hunger was unbearable. This time, I could only share with my father the half liter of soup I got at the resort (tailors). Weeks and months of despair and helplessness. The pink and shiny clothes I sewed for the German ladies were stained with tears from my eyes.

Jews in the Lodz ghetto pushed into line to receive their daily ration of soup

These weeks are engraved in my memory; every time I fearfully took my soup, the smell intoxicated me. Before I started eating, I counted how many potato cubes were in it. I had to divide them in two, for my father and for me. Out of fear, I started eating. The soup was delicious, too delicious. I wanted to eat slowly, to delay this pleasure. I didn’t have time to enjoy it and already had to stop. I took another half spoon, another drop, and was horrified to see what was left. Master of the World, I almost didn’t eat and there was already so little left. What will I bring to my father?…

My father never said a word to me. He understood my struggle, he felt it. He would blame himself: because he steals my share from me.

Now I remembered Ruchelke in her daily battle with hunger. Again, not her fault for not leaving more bread for her brother (the description of this Ruchelke will be given later). Now I understood her; I was like her. I too sat and cried when I had a little soup left, when I could not control myself and ate another spoonful.

This struggle, day by day, drove me out of my mind, every day as I vowed to eat only three spoons of soup, maybe four, but no more than that. Sometimes I managed to stick to my decision and then I was happy; sometimes I didn’t and then I sat and cried.

I called Dr. Kaspiecki again. My father stopped walking completely. “Lack of calcium in the bones,” stated the doctor. This disease is also common in the ghetto, it is also caused by hunger, but there is a cure for it, a miracle salve called “Vigantol”. It contains vitamins, a lot of vitamins. This medicine has the power to help. He, the doctor, is sure that after my father finishes one bottle, he will start walking again. The problem is, how to get the medicine. It is only distributed in one place. At the police, at the sonder-kommando. The pharmacy in sonder-kommando opens at eight thirty in the morning. But the lines there are very long, and only twenty-five bottles of Vigantol are distributed per day. Doctor Kaspiecki looked at me and sighed:

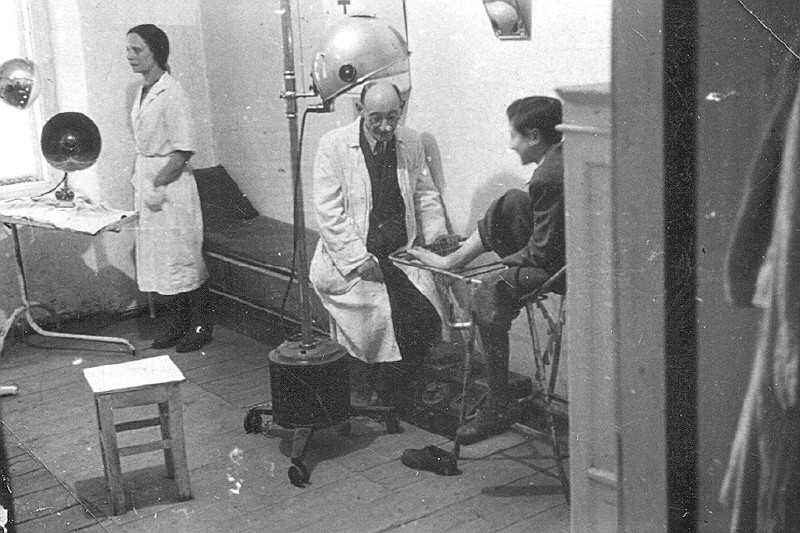

A doctor checks a patient in the clinic in the Lodz Ghetto

“I don’t believe you will be able to receive the medicine, you are so thin and weak, people have been waiting there since five o’clock in the morning. And maybe even before that.”

The doctor prescribed my father the wonder drug Vigantol. Again he gave us two slips for two kilograms of peels and went on his way.

I looked at my father. Deep despair was in his eyes and he whispered: “The thought that I myself can’t go get the medicine is terrible, I’m still young, I don’t have any pain, I just can’t walk, and there is medicine that can help me and I’m at a loss.”

“Father,” I said, “if you were able to go and bring the medicine you wouldn’t need it at all. But don’t worry, I’ll get the medicine. You’ll get it tomorrow.” Father looked at me sadly, and spoke to me through the tears in his eyes: “You won’t be able to get it, my daughter, you heard what Dr. Kaspiecki said, only twenty-five bottles per day and the lines are very long. It’s not for you, you’re so small and weak.”

I didn’t answer him anymore, but my decision was to get the medicine no matter what.

That night I got up before four o’clock. Father objected and protested:

“You won’t succeed, it’s a waste of your strength, it’s still too early, it’s dark outside, a snowstorm.” “Father, don’t disturb me, I said that I have to bring the medicine and I want to be the first.”

“But you forget that the gate is still closed,” Dad reminded me, he meant the gate on Zagirska Street.

The houses on Zagirska Street were within the ghetto, but the road was outside it. There were wire fences on both sides of the street. In order to pass from one side of the sidewalk to the other, it was necessary to pass through two gates, which were guarded by Jewish policemen, as well as a road, which was guarded by a German sentry. There was also a bridge that connected the two sidewalks of Zagirska Street, but since the bridge was very far from where I lived, I had to go through the gates. The gates were closed at night and opened only at dawn.

My father begged me to take a slice of bread with me – his portion or half of his portion. He is not hungry, he will be able to sleep and not feel hungry, while I will be very hungry, because I will have to stand in line for hours. I didn’t listen to him. I explained to him that these are hours of sleep and therefore do not feel the hunger, I will not touch his bread, therefore, and if I eat my portion now, I will be hungry all day.

I put on my coat and my father’s hat, a cap with earmuffs. With this hat on my head, it was impossible to tell that I was a girl. I went out into the street. A fierce snowstorm greeted me, the night was dark, the wind raging, almost pelting. I felt my way through the dark streets and reached the gate. A gas lamp was above it. The gate was still closed. I stood next to it, holding it so that the storm wouldn’t knock me down. The policeman and the sentry, seen through the raging snow, looked at me in bewilderment. The policeman told me that I better go to sleep until the gate opens. I answered him that I would wait for it to open. I have to get medicine for my father and I want to get to the pharmacy before a lot of people gather there.

The German sentry walking in his high boots, wrapped in his coat, stopped now and then, glancing at me. He did so until he turned to the policeman and asked him what this boy was doing here at night. The policeman told him. The soldier continued to pace back and forth. After some time he turned to the policeman and ordered him to open the gate so that I could pass. The gate was opened, therefore, especially for me.

I got to sonder-kommando, and it turned out that I wasn’t the first. The pharmacy was on the first floor. Twenty-two steps led up to it. On the stairs, in the darkness of the night, stood curled up figures, shivering with cold. These were people who lived on the other side of the street. They did not need to go through gates. I counted them. There were five in number. I breathed a sigh of relief, I was the sixth. I calmed down, they will distribute twenty-five bottles.

It was half past four. The storm outside did not stop. I stood trembling and my teeth clenched. I felt intense stabbings in the fingertips of my hands and feet. I thought about the new shoes. What luck, because I have such shoes, despite the storm, my feet remained dry. The hours crawled lazily. Each time another figure emerged from the darkness, covered in snow and shivering with cold. The figure stood behind me, but there were also those who stood before me.

One man claimed that he was already here before I arrived, he claimed that he left and now he is back. The man standing before me confirmed this. He even said that there was another woman here, and she was in line before me. I didn’t believe him. When I arrived, he didn’t tell me this, but even if I was eighth in line, it wouldn’t be too bad. The line behind me grew longer. The woman came and stood before me. I went down two steps back. Two more people arrived, and claimed to have already been here, and were therefore pushed in front of me. I protested and resisted. I said I would not agree. They pushed me and I went down two steps again. I was already the tenth. That’s not bad either, I said to myself.

The gloom began to fade. The man standing in front of me took out a slice of bread and started eating. I envied him. I was starting to get hungry. It was already six o’clock. In an hour and a half, the distribution of the medicines will begin. My legs froze, my teeth chattered. What to do to make time pass faster? Maybe I’ll try to reflect on the past, when I still had it good.

Loaves of bread that were distributed to residents of the Lodz Ghetto

One thing that happened – even then my legs froze, where was the matter? I remembered.

It was a winter day. I got ice skates. My uncle Hersh brought me the skates from the Genia factory. They were new and shiny – from a material that does not rust. I was very happy. The features around the blades was great. I got a “training”, a special outfit for skating, and even new shoes. My father went with me to a special ice rink in Poniatowski Park.

I got my first skating lesson. My father sat in the sled and I had to push him. It was infinitely more difficult than I imagined. The tips of the skates were very thin. I had the feeling that I was walking on knives. Each time one of my legs bent, and when I got on the ice surface my legs started to slide, but each in a different direction. I fell down. I didn’t have time to get up and I fell again. My father laughed. I was very offended, ashamed, and angry. My father calmed me down, spoke words of encouragement, and said that one day I will dance on the ice. At the end of the lesson I improved; my father praised me, he said that next time I won’t have to push a sled, he will skate with me, he will also get skates, and we will skate together. I was not satisfied with my achievements. Crying and frozen, I returned home. I wanted to hear words of encouragement from my mother as well; I received it generously from her. My mother put me to bed. She brought a bowl full of snow, rubbed my hands and feet with it, warmth spread through my body. I got a cup of hot cocoa. Mother sat next to me, caressed and pampered me. I had it so good then…

A snowy street in the Lodz Ghetto

Immersed in my memories, I didn’t feel how people came and pushed me and how I kept going down the stairs. Now I was already in thirteenth place, but I knew that twenty-five vials would be distributed and there was, therefore, no room for concern. I would receive the medicine.

The sun had already come up; the line grew longer and longer. People came and stood next to me. Everyone began to push, a double line would form. At eight o’clock two policemen arrived. They have batons in their hands, and they started to “arrange” the line.

“What’s that? Double line? Triple line? Down the stairs, everyone down. Boy, go down!” they shouted at me.

“But, sir, I was standing there, upstairs, I came early. I was the sixth…”

There was no one to talk to. Noise and pushing, crowding and commotion. Each time I had to retreat, until I found myself below, on the ground floor. The noise increased, the policemen used their batons.

“Don’t push!” they shouted

The pharmacy door opened. The lucky ones who were first, started to descend, each holding a bottle of Vigantol – the precious liquid. I looked at them with envy.

There was silence. The distribution now went well. We started climbing stairs. Again some people came down with the medicine in their hands. From time to time I moved forward and went up and being right next to the door, it suddenly closed in front of me. The policeman standing by the door announced that the distribution for that day was over and it would resume tomorrow. We were ordered to disperse.

I was shaking all over. I was like a wounded animal. I jumped towards the door, slammed into it, kicked in with my new shoes. I screamed and cried.

“I won’t leave here without the medicine, I was the sixth in line,” I shouted, “People pushed in front of me and pushed me down.” The people had long since dispersed and I continued to make my hysterical shouts. The policeman struggled with me, he ordered me to go. He advised me to come tomorrow. I held on to the door handle.

“I won’t come tomorrow, tomorrow the same thing will happen again! I never manage to get anything! This time I won’t give up! My father is very sick and has stopped walking. The doctor said that only Vigantol can save him. My father will not allow me to come here a second time, I myself was sick and I just got out of the hospital!”

I have never shouted like that in my life, I didn’t know I was capable of shouting so much. To this day I don’t understand how I could have uttered such screams, but today when I remember all these, I am not ashamed, on the contrary, I am satisfied because that is indeed how I acted.

The pharmacy door opened. Another policeman came out to me.

“Stop screaming already! Get out of here quickly!!”

He pushed me, I fell. But in the fall, I managed to put my foot between the door and the doorframe. They couldn’t close it. They tried to pull me, I held on to the doorframe. I kept shouting:

“It won’t help you! I will not return home without the medicine, I will stay here until tomorrow morning!” I added to the story that I was the first to pass the gate, that the German soldier opened the gate for me, that I left the house at four o’clock in the morning and that I was the sixth in line. I added more by shouting that my father is dangerously ill, that he is unable to walk.

My voice was hoarse, but I didn’t stop screaming. A man in a white coat came out of the pharmacy. He approached me and asked me for the doctor’s prescription. He had a small vial in his hand. With trembling hands I handed him the note that Dr. Kaspiecki had given me. I grabbed the bottle from him and hurried back home happily. My father couldn’t believe that I indeed managed to get the medicine. I didn’t tell him how I got it and what happened to me. I didn’t want to hurt him, but it was all worth it. The medicine helped him. It was indeed a miracle cure.

Four days later, when I returned from work, my father opened the door for me. He was dressed. All shining and happy, he swept me into his arms.

“Look, I’m already walking! I can even run! I have strength! I’m strong!” He laughed and cried alternately. like a happy little boy.

My Uncle Avraham, my Aunt Faiga, Salek, Lola, Avramek, and Gucia – they call came to see this wonder. Father demonstrated his walk to them. I was mesmerized.

(HaAtara Sheh’Avda, pg. 107-113)

Later, Sarah tells that when her father’s condition worsened, he was hospitalized on the eve of Passover in the hospital in Marysin (in the ghetto). And she, who felt an optimistic feeling that he would receive proper care in the hospital, was filled with happiness and went to the cemetery, to her mother’s grave, to share her good feeling. Read about the little girl’s efforts to save her father from death… read and cry:

(This section is taken from Ha’Isha Ba’Shoah – Eibeshitz)

That very evening, with a pounding heart, I knocked on the door of their house. With a kind smile, Mrs. Leider opened the door for me. I told her in a stutter that I was asking for her husband.

I was immediately invited to come inside and eat dinner with them. Stunned, I stood in the doorway, I thought it was a mirage in front of me – a table set, with a white tablecloth on it – a loaf of bread, cheese, sausage, margarine, jam, a pot of coffee, and sugar!

I had long forgotten that this all existed. A set table with family members sitting around it.

With a forgiving smile, Mrs. Leider invited me to sit. A plate with slices of bread was served to me.

“Eat, please, spread margarine, take something,” the family members begged me.

With trembling hands I put spread on the bread. I didn’t dare reach for the delicacies, even when the doctor’s wife put a slice of sausage on my bread, which made me really drunk, I couldn’t swallow the food when I remembered my sick father lying alone. My chin started shaking, I was afraid that I would burst into tears. Doctor Leider came to my aid by asking me about the state of studies at school. The pleasant atmosphere and the kindness of the people of the house somewhat distracted my mind from my troubles, and filled me with the courage to present my request to them.

I told about my father’s illness and memorized the words of Dr. Kaspiecki, that only a hospital can save my father. And suddenly, without feeling it, I found myself telling about our house from before the war, memories that since my mother’s death I didn’t even dare to think about.

My hosts listened to me attentively. Dr. Leider promised me that he would take care of the matter. He himself will go to the hospital, the very next morning. I thanked him with tears in my eyes from excitement. A spoonful of powder from a jar was put into my coffee mug. The powder whitened the coffee and reminded me of the smell of milk. The sugar container was moved towards me. I took three cubes. But seeing that no one was looking, I only put in two, I kept the third for father.

Excited and happy, I ran to tell my father about the doctor’s promise and the wonderful evening!

I think for more than an hour I meticulously described the table and how it was set.

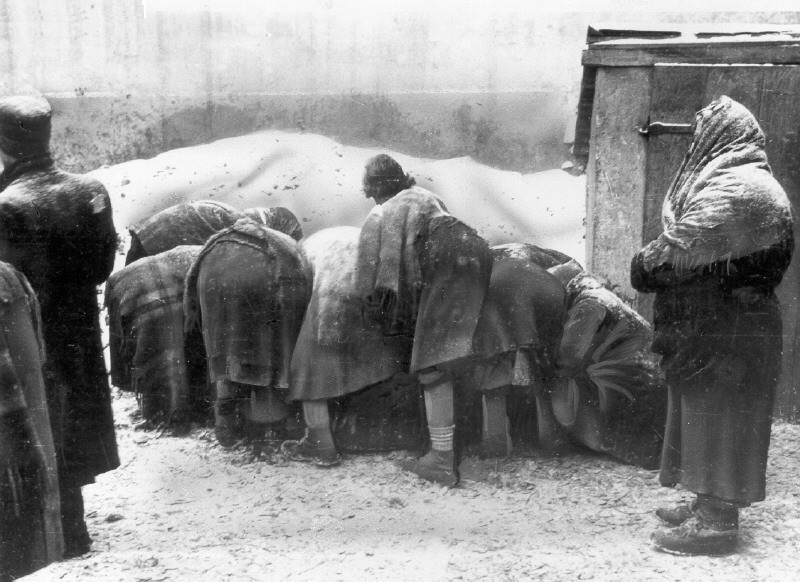

Women search for scraps of food in garbage cans in the Lodz Ghetto

My father looked at me, and while sucking the sugar cube sighed.

“My poor child, who can now think that only two years ago your mother was chasing you with an apple or a buttered bun in her hand.”

A buttered bun? An apple? After all, these also existed! And only two years ago!

Only two grades. And it always passed so quickly: summer and winter, summer and winter. Now it seems to me that many years have passed since then.

Dr. Leider kept his promise.

With a heavy heart, I went the next morning to my father, pondering the troubles of the day that lay ahead of me: lighting the fire, cooking the kohlrabi, and worst of all – the fear that I might look out the window and not find my father alive. I went around full of fear. A white cart with a red cross painted on it drove in front of us, it drove in the direction of our house. My heart pounded greatly – could it be? I started running to get ahead. I broke into the house. My father lay awake.

“Father! My father! I thought they came to take you!”

I didn’t have time to finish the sentence, and two people entered the room with a stretcher. My father’s face shone with happiness:

“Indeed G-d helped us, I will get well, I will be strong, I will take care of you, I was already so discouraged, I did not believe that I would ever recover from this illness.”

Happily, I hugged my father, I thanked these people.

The white wagon with my father disappeared and I hurried to run to the cemetery to tell my mother about the miracles that had happened since yesterday evening. I was sure that her efforts from above helped.

In the following days, I felt great relief, as if a heavy stone had been lifted from my heart.

My father is now in good hands, he is being taken care of, and he will get well. After all, he is strong by nature and also young. We heard that the patients in the hospital are given enough food.

The Expectation that was Disappointed

My father’s smile and wave of his hand filled me with hope. I happily returned, therefore, to the resort. The thought that he would receive proper treatment in the hospital, because he would still have time to reach the hospital before lunch and receive a hot soup, filled me with endless happiness. I was so happy that I started singing. My mood in the last few days had been depressed. My father’s illness depressed me greatly, and now I was the first to start singing. I was sure my father would recover. The girls smiled at me and also joined in my singing.

At the end of work, I wrapped up my portion of bread and rushed to the hospital. This time they took my father to Marysin Hospital, where I had also been hospitalized. The intelligence officer knew me, and he also remembered my father. I happily spoke to him like an acquaintance and told him how lucky we are, that we still had time to receive both matzah and the new dish, because we also have bread for three more days, until it actually would be Passover.

“Every day I will come bother you,” I said with a smile to the intelligence man, “Now I have brought for my father one portion of bread, maybe he will eat it in the evening, so that he will not go to sleep hungry. I will also bring him bread tomorrow and the day after, and on Passover I will bring him matzah.”

The man listened to my excited words. I felt that he was also happy with my happiness. He promised me that he would give the bread to my father, with his own hands he would give it to him and also tell him that he talked to me. I thanked him. Everyone suddenly seemed good to me, so good, I almost forgot the people who didn’t let me say goodbye to my father.

(HaAtara Sheh’Avda, pg. 124-125)

The next day, I grew even happier when the intelligence officer informed me that my father was feeling well and he was no longer hungry. Not so on the third day. From a distance I saw the intelligence officer and he was standing behind the counter, I smiled at him and waved goodbye. I was almost certain that he saw me too, but contrary to his constant kindness towards me, he did not respond to my greetings, as if he ignored me. This puzzled me.

Maybe he didn’t notice me, I said to myself. But even when I approached him and greeted him again, the man turned his head away and continued to stand with his back to me. Maybe the man is nervous today, I continued to ponder.

“Sir,” I said, “only today I bring bread for my father, tomorrow will be Passover and I will bring him matzah.”

The porter bent down, he took something out from under the table, turned to me suddenly and without saying anything, placed two packages on the counter. I was horrified. I knew the packages. These were the two portions of bread that I brought for my father the day before and yesterday. With a look full of irritation I looked at the man. Why?… Why didn’t he give the bread to my father?… After all, he promised he that he would give it. He promised that he woiuld deliver it with his own hands. He just told me yesterday that he had delivered it. Well I was lied to. Why did he lie? What did I do wrong to him? And I thought of him as a nice person…

“Sir!” a scream burst from my mouth, “why didn’t you give the bread to my father?! My father is hungry, he is waiting for this bread! I promised to bring him the portion of bread every day, after all, I told you that we had three more portions of bread left and that we managed to get matza. My father will think that something happened to me, that maybe I got sick. Tomorrow he won’t be able to eat the bread anymore, because tomorrow is Passover.” I started sobbing.

Transferring loaves of bread to the distribution stations in the Lodz Ghetto, under guard

“Why did you lie to me?”

The man didn’t look at me. He spoke to me quietly, with his eyes fixed on the counter:

“Listen, child, I know I’m not okay. Because I lied to you.”

“But why? What did I do to you?!” I let out a scream.

“Because I couldn’t do otherwise,” said the man, “because I felt sorry for you. Your father died. On the same day he was brought to the hospital, your father died. I couldn’t tell you. You came with the bread and you were full of hope and joy, so I couldn’t tell you. I remembered you from the days when you lay here and fought for your life. I remembered your father when he stood here all night, in the cold winter night, and prayed for your well-being… I did not have the courage to disturb your joy, and tell you about your father’s death.”

At first I didn’t understand the man’s words. And suddenly a thought pierced me all over: my father is dead! He didn’t even have time to eat the hospital soup… My father is gone… I won’t see him again… Never… The man continued to speak:

“I know I wasn’t right to you, but I thought to myself – be happy for another day or two. Think that your father is still alive. You’ll have enough time to grieve. Today I had to tell you. Because tomorrow morning at nine o’clock your father will be brought for burial. Wait by the entrance gate to the cemetery”…

G-d, Take Away my Understanding…

…Early in the morning I was already at the gate of the cemetery, I waited for a long time until the black cart arrived, the first dead person taken out of it was my father. At his feet was tied a small can with the name Anshel Kalman Felger…

Two gravediggers took him down on a stretcher. His face changed a lot, his eyes were open and filled with question and fear. The gravediggers complied with my request, they wrapped my father in his blanket and closed his eyes. But they didn’t wrap it well. His bare feet remained. I followed the gravediggers. I didn’t cry anymore. I couldn’t cry. The gravediggers lowered my father into the grave. I didn’t cry even now. Only my throat was choked. Here we are parting forever, and I, who loved my father so much, am not even crying.

One of the gravediggers took out a penknife and made a tear in my sweater. After that, they threw a few clods of earth into the grave and already asked to leave the place and go. I protested. I demanded from them that they finish the burial. It’s Passover today, was their answer. It’s the first day of the holiday and they don’t work all day. On top of that, a lot of work awaits them. They must bury the rest of the bodies. My pleas were of no avail. I was one of many for them. And my father – just a body that had to be lowered into the ground.

I was helpless. I felt that I must not leave father like this, leave him uncovered and ashamed. I myself was so in need of encouragement and support at that moment, I suddenly felt that father needed my help, therefore I must not leave here.

I just started crying. One of the gravediggers came back to me. He gave me his shovel for a few moments only, until they buried the rest of the bodies. I began to cover my father with earth. Throwing soil at my father was horrible…

“G-d, give me strength. Take away my understanding, G-d, so that I will not understand or know what I am doing.” Every additional clump separated us. Soon he will disappear completely, forever. Don’t think, just don’t think. I have to finish fast. Before they take the shovel away from me…

I suddenly remembered. It’s my birthday today. The first day of Passover. What a great day this always was. A day of celebration and gifts.

“Father! My father, do you remember that today is my birthday? Your only daughter’s birthday?” No, I must not think about that either. I must not feel sorry for myself. I am still alive, while my father is no longer alive.

I finished the funeral. I also piled a small mound on the grave.

(HaAtara Sheh’Avda, pg. 130)

Ruchelke – A Heartbreaking Description

Ruchelke sat on my right. A girl of about eighteen whose ends of black hair touched the bandage around her neck. Her bandages were first white, then gray and finally black.

Ruchelke had big black eyes and they would burn with a strange fire. An unpleasant smell wafted from her. A smell that grew stronger over time. At the beginning of our acquaintance I asked her if her throat hurt. She avoided answering. Mrs. Frankel hinted to me not to ask questions, then told me that Ruchelke was infected with a terrible disease, “Active Tuberculosis” it was called. I got over my dislike and became friends with my neighbour. Her story was sad. She came from a rich family and until the war she was only immersed in studies.

Her mother, also from a rich family, was a spoiled woman. Ruchelka and her little brother, Chaimke, were raised by servants. When the war broke out, her father received a conscription order, and since then he disappeared and nothing was heard of him. Her mother and her two children moved to the ghetto, but the mother quickly broke down, for hours she would sit by the window and look at outside with glassy eyes. She didn’t even respond when her children spoke to her. She became indifferent to everything and gave into bitterness. She also stopped eating.

The whole load now fell on her Rachelke. She took care of her mother and little brother, until one day she found her mother sitting lifeless. From then on, only she and her brother remained. Only she got a job. Her brother was seven years old, but he looked like a four or five year old boy.

Sick and exhausted Jews, who were deported to the Lodz Ghetto, being deported to extermination

Every day, after we would receive the bread ration at work, I saw Ruchelke struggling with herself. She would put her bread aside, go over and tear off only one crumb at a time. She had a strong desire to leave something for her brother but rarely succeeded in doing so, because she could not overcome her hunger. And when she failed to leave him anything, I saw her sitting and crying.

She praised her brother in front of me, the good boy, who cleans the house and also stands for hours in the long lines. She invited me to come to her, and once I even accepted her invitation and came to visit her. From the moment I entered the stairwell, the familiar and menacing smell reached me, which grew even stronger when her brother opened the door for me. I recoiled at the sight of the boy, as if a monster stood before me. Chaimke had a large head, which in no way suited his thin and small body. Two big, black,and fiery eyes like his sister’s eyes. Later I found out that tuberculosis patients have shining eyes like this. He was wearing short pants, baggy, and wider than his size, the pants were tied with a rope around his waist.

Ruchelke handed me a chair. Again, I overcame the desire not to sit down. I sat and talked to the boy. His voice was also as if not his own. An old, raspy voice spoke to me. The boy knew that two days later they had to get a ration. He also knew from the rumour that we would get 100 grams of jam. I was very upset when I left their home.

A few days after the visit, Ruchelke did not come to work, so I went to her house. When she opened the door for me, a terrible stench hit me. I held my breath. On the floor I saw something wrapped in a blanket. To my panicked question, Ruchelke answered in a dry voice: “My brother died yesterday afternoon.”

In fear I looked at the blanket.

“And why didn’t you let them know so that they will take him? Why are you leaving him like this?” I shouted.

“Look Selusia” (Sela, Sarah’s Polish name) Ruchelke said in a hoarse voice, “He’s already dead either way, and tomorrow they’re distributing bread.” If I had notified them yesterday, they would have taken his card from me. And so I will still have enough time to receive his bread portion.”

“Will you keep him here until tomorrow?” I asked in a panic.

“What is there to do? Lose the bread?” I heard her answer her own question.

In a crazed run, I ran away from there.

(HaAtara Sheh’Avda, pg. 62)