Damascus and Beirut – Jewish Memories

In this fateful period, in light of the upheavals in Syria and Lebanon, we recall their recent Jewish history and bring up memories, both more recent and old, of a Jewish existence that was and is no longer.

By: Yaakov Rosenfeld – Article 1

The Magen Avraham Synagogue, Beirut

100 years ago, in the year 5685 (1924-5) the Magen Avraham synagogue was established in the Jewish quarter of Beirut, located in Wadi Abu Jamil, northwest of Beirut, Lebanon.

The synagogue was the center of the Lebanese Jewish community, and in addition to it, there were two other synagogues in the neighbourhood: one for Spanish speakers (who came mostly from Greece) and the other for Ashkenazim (who came from Eastern Europe). The neighbourhood was home to the centuries-old Jewish community as well as to Jewish refugees from Syria and Iraq in later periods.

The interior of the Magen Avraham synagogue in Beirut

The synagogue, which is no longer active, was damaged in the First Lebanon War by a missile strike and was restored with great investment by the Safra family from Switzerland (originally from Lebanon), and in August 2020 (Av 5700) it was severely damaged by the explosion that occurred at the Beirut airport.

The large and magnificent synagogue was an integral part of the cultural life of Lebanese Jewry. After the Holocaust, it served as a transit station for illegal immigrants who entered the Land of Israel, and even after the establishment of the State of Israel, when Lebanese Jewry dwindled, the synagogue was still an important Jewish center until the 1990s, when the Lebanese Jewish community almost ceased to exist.

From this synagogue, Salim Murad (Shlomo), son of Mordechai and Zakia Jamus, was kidnapped and disappeared, and his whereabouts are unknown to this day.

Salim, born in Aleppo, Syria (born in 5692/1932), moved to Beirut in his youth, where he married Mary and raised Moise (Moshe), Mordechai (Marcel) Moti, and Shalom (Charles). The family lived in a luxurious house in Beirut, the capital of Lebanon. Salim was a successful textile and real estate merchant. He had an office inside the Magen Avraham synagogue, and in addition to his business, he was the chairman of the Jewish community in Lebanon and took care of all the Jews’ needs. His wife Mary was also active in the community, and she made a significant contribution to the immigration of the Jews of the Damascus community to Israel.

Salim tirelessly assisted those seeking to immigrate to Israel and was involved in many operations that were a well-kept secret. In his home, he hosted Shin Bet and intelligence officers, and offered shelter to immigration activists. As treasurer of the synagogue, he hosted senior Israeli officials, including senior IDF officials Ezer Weizmann, Arik Sharon, Itzik Mordechai, Ehud Barak, and others. He also managed to smuggle the community’s very ancient holy books and Torahsinto Israel, and the books ended up in synagogues in IDF intelligence units.

In 1978, Salim was kidnapped by Lebanese security forces from the Magen Avraham synagogue and underwent a series of harsh interrogations and torture in prison. After several weeks, he was released after his family paid the authorities. In April 1979, he was kidnapped again, interrogated again, and released only after his family paid a ransom.

(Courtesy of A.P.)

On August 15, 1984, Salim was kidnapped again from his office. The kidnappers, members of the Syrian National Party (PPS), an organization operating from Lebanon, burned the office and wrote “Jew” on the wall. His kidnapping was discovered by his son Moshe, who had come to visit the office.

A few days later, his wife was offered the chance to give up her son and take her husband back. She of course refused, moved from her luxurious home to a simple one, and continued to fight to obtain information about her husband and bring about his release.

However, the fight was unsuccessful, and nothing was known about Salim. It was clear to Mary that her family was in danger, and in 1989 she managed to escape from Lebanon and immigrate to Israel with her three children, to Kiryat Ata.

Salim, may G-d avenge his blood – kidnapped in Lebanon and murdered in Syria

“Mivtza Melet” (Operation Cement)

The Magen Avraham synagogue was a central and important anchor in “Mivtza Melet” carried out by the Mossad during the years 1969 to 1972 to bring back about four hundred Jews who had fled Syria. The Jews, mainly boys and girls from the cities of Aleppo and Damascus, would cross the Syrian-Lebanese border and arrive on their own initiative in Beirut. Every time a group of several Jews was organized, contact was made with the Mossad at a relay point in Europe. The Israeli navy would send out a naval force that included a Davor ship to meet them and missile ships for security off the coast of Beirut.

The escapees would gather at the Magen Avraham synagogue in Beirut and from there go to the shore. At the shore, a contact person who owned a racing boat would meet them and would set out with them to the sea in the evening. After sunset, the messenger would arrive near the shore, locate the boat, pick up the Jews, and make his way back to the port of Haifa.

The voyages were carried out with high levels of compartmentalization. The normal combat procedure was not followed. No written orders were issued, no investigation was conducted, and the commander of the operation did not issue summary reports.

On one occasion, due to a misunderstanding, there was a delay in the naval force’s departure for the meeting. Assault ships were launched for the mission, which were twice as fast as the Davor. The head of the Mossad, Tzvi Zamir, with the approval of Prime Minister Golda Meir, set out with the naval force to collect the immigrants.

The meeting with the escape boat took place with a slight delay. The escapees were put on the missile ship but were terrified and afraid. Mossad chief Zamir said that no amount of talking in Hebrew or Arabic helped. Until an idea flashed through his mind and he said, “Shema Yisrael, Hashem Elokeinu Hashem Echad” (Hear Oh Israel, the Lord Our G-d, the Lord is One). The eternal Jewish phrase convinced and calmed the refugees, and only then did they believe that the missile ship was Israeli. Zamir told the prime minister about this, and she was also moved.

In the Valley of the Shadow of Death

In the book “B’Gai Tzalmavet” (In the Valley of the Shadow of Death), the Jewish spy in Lebanon, Mrs. Shulamit Kishik Cohen z”l, tells of the life of the Jewish community in Lebanon during the dark years, which was intertwined with the life of the Magen Avraham synagogue and the entire Wadi Abu Jamil neighborhood.

The following is a selected excerpt from a breathtaking story, from which we can see how meticulous the Jews of Wadi Abu Jamil were about honoring the dead and the customs associated with this mitzvah.

Beirut, Lebanon

“More than we preserve the religion, the religion preserves us”

On Yom Kippur 5718 (1957), during Neila (the closing prayer of the holiday), when the Jews were exhausted from fasting and turned to heaven, awaiting the sound of the shofar heralding the end of the fast, blood-curdling sounds reached our ears from the entrances to the Wadi on the Bab-Idris and George Picot roads.

Our haters knew that at this fateful hour we were gathered in the synagogue, our bodies weak and unprepared to defend ourselves against them. None of us imagined that they would provoke our G-d and desecrate the sanctity of the day.

It came as a surprise. Gunfire was heard, and stones flew toward the Jewish neighborhoods. Three tanks at the disposal of the excited crowds approached the Alliance School and the Magen Avraham Synagogue. The calls for the killing of Jews grew louder, and in the air echoed the slogan that had been heard in Israel during the bloody riots of 5689 (1929): “Alihom! Alihom! Palestin baladna v’elyahud klavna” (Palestine is our land and the Jews are our dogs).

(…)

Fortunately, there were no direct casualties from the direct attacks of the protesters, but a Jew suffered a heart attack while still in the synagogue and collapsed. Doctors were called and he was taken to the clinic for intensive care. He lay there unconscious for several days, until death overtook him and he surrendered his soul to G-d.

To reach the cemetery to bury the deceased, one had to cross a section of the Basta Square, populated by Muslims.

The authorities forbade eulogizing the deceased in the synagogue courtyard and also decided to prevent the funeral, claiming that any gathering posed a security risk.

Pressure was applied. On the eve of the holiday of Sukkot, it was made clear to government representatives that according to Jewish law, the deceased could not be buried – and the holiday was approaching.

In the end, a limited funeral was permitted. Only ten members of the chevra kadisha (burial society) were allowed to accompany and bury the deceased – enough to complete the minyan (prayer quorum). The authorities also forbade the family members of the deceased from accompanying their loved one. At the last minute, the mukhtar (head of the community) was also allowed to join the funeral procession.

The holiday arrived, the nightly curfew came, and the men who had gone to the funeral did not return.

The men’s wives were seized with anxiety for the fate of their loved ones. They waited outside and refused to listen to the policemen’s calls to enter the houses. The women announced that they would not enter until the husbands, who had left with police permission, returned home.

The night passed, dawn broke, and there was no sign of the missing.

A commotion arose. The people in the district were confused and afraid. They claimed that we had reached a situation where the living were not allowed to live and the dead were not allowed to die with dignity.

The police officers in the Wadi did not know how to answer the questions. They had no idea where the missing people were. There was concern that the people had been kidnapped by hostile militiamen.

(Shulamit later describes what she went through on her way to the Islamic militias’ “Valley of the Shadow of Death,” and the revealed miracles she experienced until she managed to make contact with one of the terrorist leaders, and after she devoted herself to visiting his elderly mother, she succeeded in freeing all ten men from certain death. There is no room in this article for all the details, but we will provide a few moving details.)

She turned to her son with a scolding, saying that she had been expecting his arrival for a long time.

I was amazed to see how this man, to whom so many kidnappings and murders are attributed, squirmed and writhed before her, like a little boy who had been naughty.

The tall, sturdy Abu-Mustafa had to bend almost to his full height to kiss the back of her hand and apologize for being late.

“Yamma, I have brought with me a wonderful woman. She has come on matters related to the Jewish community she represents. Meet her: this is Umm-Ibrahim.”

She greeted me warmly and came across as a kind and lively woman. She spoke pleasantly, in a melodious and friendly voice, and I felt less intimidated.

“May Allah protect your Abraham,” she greeted me. “Do you have any more children? May Allah bless all who come from your loins.”

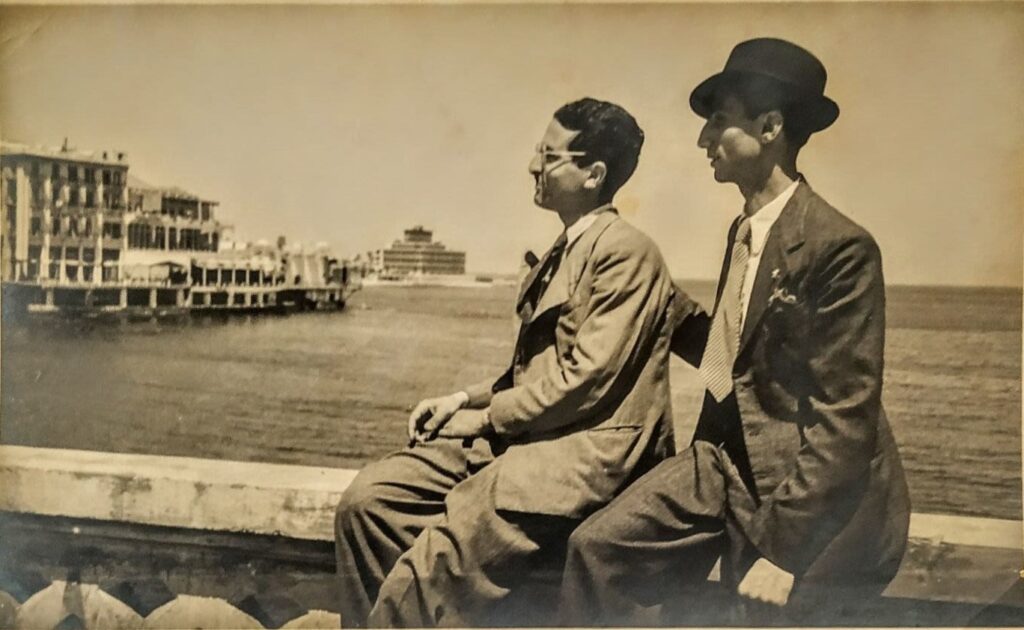

Jews next to the Beirut port in 1930

When I replied that I was a mother of seven children, she expressed surprise that I was still devoting my time to addressing public problems, and asked:

“May I know what the important things are that you went to all this trouble to come here for?”

Hearing my words about the people who had disappeared from us, she asked: “Are some of them your relatives, that it was so important for you to leave a home with children and come to a place where a dangerous war is taking place?”

I replied to her that although I have no relatives among the companions of the deceased, according to the education I received from my parents, I am unable to ignore the plight of people.

“I collect donations for the poor, visit the sick and make sure they receive proper medical care,” I explained to her, “and by the way, when I saw your wounded groaning in the pharmacy, for the first time in my life I regretted not having studied medicine and not being able to help them. In any case, that’s when I decided to donate to help their families. It goes without saying that when I learned that twelve of our community members had been kidnapped, I saw a need to come to their aid.”

“Kidnapped? What do I hear?” she asked her son, a question that sounded like a rebuke.

“There was a mistake here,” the son replied apologetically. “My people saw strangers entering our area after receiving explicit instructions on how to behave. They did not know how to distinguish between people with malicious intentions and innocent people who wanted to accompany a dead person. I have already made sure that everyone is released as soon as possible and returned to their families.”

“Yoh abni, yoh ruchi” (Oh my son, oh my soul), she said to her son. “Whatever Umm-Ibrahim tells you, listen to her voice, and may Allah bless you in everything.”

And then she turned to me: “You are a good and brave woman. Today it is difficult to find people like you, perhaps only in the days of Muhammad. Tell me, how is it that you were not afraid to come to my son despite such dangers?”

“Lo techaf min ha’eli b’chaf rabo” (Do not fear those who fear G-d) I replied, looking at her son.

She was delighted to hear the words I said in favour of her son as “fearing his G-d.” Abu-Mustafa was also relieved and pleased by my words and laughed.

(…)

The conversation was cordial. She showed interest in Jewish life and tradition. I told her about the upcoming Sukkot holiday, the custom of eating in the Sukkah, and the upcoming Simchat Torah holiday.

She expressed admiration for how we preserve religious values, and I replied that more than we preserve our religion, religion preserves us.