In Those Days On This Date – Part 2

Chapters of history, interwoven into each other, in 6 fascinating segments

Tammuz 5785 (2025)

By: Yaakov Rosenfeld, Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

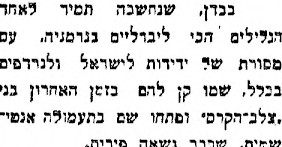

Rabbi Shmuel Strauss, founder and builder of the Strauss Courtyard

On a holy Shabbat night in the city of Karlsruhe, Rabbi Shmuel Strauss (great-grandson of the Baal Shem of Michelstadt, an extraordinary philanthropist – According to the testimony of his son-in-law Rabbi Yaakov Rosenheim, “he donated much more than a fifth of his fortune to charity”) walked gracefully from the synagogue to his home, the light of Shabbat shining before him, and inner joy welling up in his heart.

Suddenly, Rabbi Shmuel felt a lump in his pocket, and he quickly realized what had happened to him. In the morning, he participated in the celebration of a circumcision, wearing his Shabbat clothes, and accidentally left all his belongings in the pocket of his coat, in addition to the many savings that gentiles and Jews had deposited with him.

In the heart of the city, Rabbi Shmuel was agitated and confused. He understood the consequences of his actions. In his mind’s eye, he saw the ignorant multitude of gentiles who had entrusted their property to him, as a petty and loyal banker, wanting to devour them alive in a fit of rage. He saw his Jewish brothers who were impoverished in an instant as a result of his negligence, and he did not know what to do. He understood that he was turning from a wealthy man into a persecuted debtor, but he also knew that it was unthinkable to carry money in the public domain without an eruv (a fence or string built to allow carrying on Shabbat).

Then, with a sure and firm movement, he shook the lapel of his coat, and the bundle of bills fell to the floor on the road.

A difficult test, and he withstood it. An even more difficult test was to distract himself from the whole story. He returned home and performed Kiddush with joy, and sang Shabbat melodies with a supreme joy far greater than any other Shabbat.

And after Shabbat, following havdalah (ceremony marking the end of Shabbat), after an uplifting Shabbat filled with Torah and joy of heart, Rabbi Shmuel walked briskly to that place, and to his amazement, the enormous bundle of bills awaited him, and not a single penny was taken from it.

It was a miracle, without any natural explanation.

But the story is not over yet.

The next day, one of the region’s top economic figures unexpectedly visited Rabbi Shmuel’s residence and decided to deposit all the funds of the provincial Ministry of Finance with him, which increased the value of the tiny bank dozens of times.

In that chapter, Rabbi Shmuel became wealthy, and later, among his other charitable and kindness initiatives, he established the famous “Strauss Courtyard,” where the great men of Jerusalem would study Torah. (The story was told by Rabbi Moshe Turk, the rabbi of Bnei Brak. He heard it from his grandmother, who was the daughter of his teacher Rabbi Yaakov Rosenheim, the son-in-law of Rabbi Shmuel Strauss.)

Who was his emissary and confidant in establishing the Strauss Court, and what was his connection to Rabbi Shmuel?

More on that in the next segment.

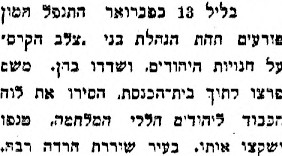

The Genius Rabbi Yaakov Shor

At the end of the month of Av, it will be one hundred and one years since the passing of the genius Rabbi Yaakov Shor, who in his lifetime was known as a rare genius and wonderfully knowledgeable in all parts of the Torah, and a posek (halachic decisor) whom all the great men of his generation abided by.

As a child, Rabbi Yaakov was already known as a “child prodigy.” He learned Torah from his father, the head of the beit din (rabbinical court) of Kitov – the city of the Baal Shem Tov. In his youth, he was a student of the “Sho’el U’Meishiv,” Rabbi Yosef Shaul Nathanson z”l, who ordained him to teach. Immediately after his marriage to Esther, the daughter of Rabbi Shaltiel Isaac Hirsch, who supported him so that he could study his Torah without worrying about earning a living, he wrote two important works: the book “Yesod HaTorah” on Maimonides, and the book “Bei Chayeh,” on Rabbeinu Bachayeh’s commentary on the Torah.

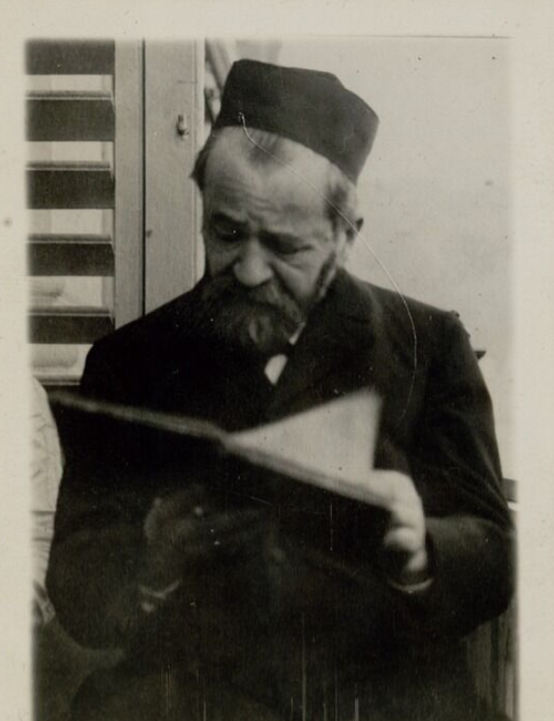

Two years after his marriage, his father-in-law passed away, leaving him a large inheritance. Rabbi Yaakov invested the inheritance money in a tallis (prayershawl) factory so that he could continue to study the Torah in peace. However, the business was unsuccessful and Rabbi Yaakov went bankrupt, due to his dedication to Torah study and his neglect of the factory and its needs.

Tallises that were brought back to the Lodz Ghetto after their owners were murdered in the Chelmno camp

And what was the reaction of his father, the rabbi of Kitov, when he learned of his son’s “shameful business”?

“There are no words to describe the great joy I feel in light of the knowledge that you lost your money in such a short time and did not abandon your Torah. And now I hope that you will return to Torah permanently.”

At the age of 25, he was accepted into the rabbinate of the city of Vatra Dornei (a resort and ski resort in Bukovina in northern Romania, now a resort town with 15,000 residents), where he served for seven years and from there he sent halachic responses to inquirers from many places around the world. He collected the responses in the book Imrei Yaakov – the first part of his responsa series. Over the years, the rabbi became known as a prolific author, and some of his books were published in new editions as part of the publishing enterprise of the “Mossad HaRav Kook.”

Below is an excerpt from the story of his wonderful life and the strong connection with Rabbi Shmuel Strauss, from Wikipedia:

In the year 5646 (1886), through the mediation of Rabbi Tzvi Yehezkel Michelson, he was appointed rabbi of the city of Ludmir. Rabbi Yaakov Shor’s tenure in Ludmir lasted only about six months; during this period, the authorities did not issue residence permits to foreign nationals within Russian territory. About a hundred of the city’s Jews, and non-Jewish residents, signed a false declaration stating that Rabbi Yaakov was a Russian national who had been given up for adoption as an infant outside its borders. At first, the ruse worked and the authorities authorized Rabbi Yaakov Shor to reside in Ludmir as a Russian national. However, following a dispute over kashrut that broke out in the city, one of his opponents reported him to the authorities, and Rabbi Yaakov Shor was sent to prison.

Rabbi Tzvi Yechezkel Michelson testified:

“One morning, as the day dawned, armed police burst into the synagogue, while the rabbi was praying wrapped in a tallis and tefillin (phylacteries), and led him in the sunlight to the prison, and it is very easy to describe the noise and commotion in the city… The citizens tried to make it easier for him and asked to bring him kosher food and books necessary for his studies from his home, and thus the noble man suffered for several weeks in the prison in the city of Ludmir, and from there he was taken to the large and harsh prison in the city of Lutsk, where he suffered severe and bitter torments for over a year…”

(Mishnat Rabbi Yaakov, Piotrkow 5690, Pg. 3)

Rabbi Yaakov Shor turned to Rabbi Azriel Hildesheimer of Berlin for help, who used the connections of Eliezer Brodsky, a wealthy Russian and a relative of Rabbi Yaakov Shor, to help the cause. Brodsky hired one of the best lawyers for Rabbi Yaakov Shor, who succeeded in having the trial overturned, on the condition that the rabbi and his family leave Russia and return to their country.

After his release from prison, Rabbi Yaakov Shor left Russia with his wife and son Alexander, and wandered from city to city, destitute. To his regret, he discovered that he would not be able to return as rabbi to his previous town, Darna, which had already ordained a new rabbi in his place. Rabbi Yaakov Shor again sought the help of Rabbi Azriel Hildesheimer, who sought the help of Rabbi Shmuel Strauss, a renowned philanthropist from the city of Karlsruhe. Rabbi Strauss offered to host Rabbi Yaakov Shor until he could get back on his feet, and a strong friendship was forged between the two that lasted until the end of their lives. During his four years of residence in Karlsruhe with the support of Rabbi Strauss, Rabbi Shor was free from worries about earning a living, being free to study and teach, and to compose his “Sefer HaMitzvot,” which was not published.

In 5654 (1894), upon the death of his wife, Rabbi Strauss decided to initiate a charitable act for the upliftment of her soul. He chose his rabbi and personal teacher – Rabbi Yaakov Shor, as his emissary, and financed his trip to Eretz Israel, with the aim of helping in the settlement project. Rabbi Yaakov Shor traveled to Jerusalem equipped with Rabbi Strauss’s money, who gave him the authority to decide how the money would be invested. After some deliberation, Rabbi Yaakov Shor decided to support a group of baalei musar (people who study musar – morality) led by Rabbi Avraham Broida, despite his affiliation with the chassidic movement. In an unusual decision, Rabbi Yaakov Shor transferred to the group the funding required to build a house outside the walls of the Old City, in the Musrara neighborhood (today Morasha), and in the house called “Strauss’s Courtyard” 10 families of Torah scholars were housed free of charge.

During that visit, Rabbi Yaakov Shor was asked to speak on the eve of Shavuot at the great synagogue “Chorvat Rabbi Yehuda HaChassid” in the Old City. His talk, which he mentioned in the introduction to his book “Etim Levina,” and left its mark on the city, and following it, rabbis approached him with an offer to settle in Jerusalem. Rabbi Yaakov Shor decided to reject the offer due to family reasons and returned to Karlsruhe.

A year later, in 5695 (1895), upon the death of his father, Rabbi Elisha Yitzchak, Rabbi Yaakov Shor was invited to fill his father’s place as rabbi in the city of Kitov. By this time, as mentioned, Rabbi Yaakov Shor, aged 42, had already served as rabbi in several communities, and his name preceded him. Rabbi Yaakov Shor accepted the invitation of the Kitov community, and said goodbye to his friend Rabbi Strauss.

In 5656 (1896), Rabbi Yaakov Shor became rabbi of Kitov, or by its official name “Kutow,” located in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains, on the border between Galicia and Bukovina, on the Polish-Romanian border. This appointment was particularly honourable, as Kitov, where the Baal Shem Tov and Rabbi Avraham Gershon were active, was considered the cradle of chassidism.

His days in Kitov were characterized by the settlement of conflicts and quarrels that arose among the local people, who were divided into two camps. Those who wrote about his life noted that he had “little means of livelihood” and suffered poverty and deprivation, but nevertheless “he did not stop studying.”

During his residence in Kitov, he was engaged in public affairs every day of the week, devoting his nights to Torah study, and sleeping a few hours every morning, after the morning prayer. Rabbi Yaakov Shor answered many letters, which were sent to him from all over the world, and his responses were printed in many rabbinical monthlies. He continued to devote a significant portion of his time to writing, and in addition to his published books, he wrote several books that were not published, and other writings, including a commentary on the Mishna, which has been lost.

At the outbreak of World War I, Rabbi Yaakov Shor remained at his home in Kitov, and did not leave his duty as rabbi even when the Cossacks broke into his city. However, with the second assault on the city, he fled from Kitov, and together with thousands of other exilees fled to a village near Vienna, where he lived for two years with his wife.

At the end of the war, he returned to his city and home, only to discover that his property had been looted and burned, and that only a few of his letters and books had been saved by his Christian neighbours.

In the last two years of his life, Rabbi Yaakov Shor suffered from a fatal illness that confined him to his bed, but, with clarity of mind, he did not stop answering letters sent to him. Three days before his death, he dictated his last halachic (Jewish law) response, “without consulting a book,” to his close associate Rabbi David Sofer.

And a little about the holy community of Karlsruhe and its bitter end, in the last segment.

The Holy Community of Karlsruhe

“Karlsruhe is a city in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwestern Germany on the banks of the Rhine River, near the French-German border. The city around the palace has become the seat of the two highest courts in Germany, the Supreme Court and the Federal Constitutional Court. The city therefore sees itself as the seat of justice in Germany, a role taken over from Leipzig after 1945. Due to its resemblance to the capital of the United States, some estimate that Karlsruhe was a model city for the urban landscape of Washington, D.C. Both cities have a center – in Karlsruhe the palace and in Washington the Capitol building – from which the streets radiate outward. The city has many interesting sights such as beautiful botanical gardens, a zoo, and impressive buildings such as Karlsruhe Palace.” (From: Explorer)

“Karlsruhe, which was considered one of the most liberal cities in Germany, with a tradition of friendship towards Jews and the persecuted in general…” (A newspaper clipping from 1926 – 99 years ago)

Karlsruhe, a city with a glorious and deep-rooted Jewish population, began to suffer at the hands of the “people of the swastika,” and so the beginning of the end of the glorious community, the city of the Korban Netanel and the Aruch LaNer, the famous Torah commentators, began.

A Jewish community existed in Karlsruhe as early as 5577 (1816-7). Thirty years later, a printing house was opened there, and Korban Netanel was the first book printed there. The Karlsruhe press also printed the book Seder HaDorot by Rabbi Yechiel Heilprin, and the first edition of the book Yaarot Dvash.

The genius Rabbi Yedidya Theo Weill, son of the Korban Netanel, who continued his path in the city rabbinate, was a wonderful genius and prolific author. He initially lived in Prague, but was expelled from there by the Maria Theresa decree. The grandson of Rabbi Yedidya, the famous genius Rabbi Yaakov Weil, author of the book Torat Shabbat and more, in the introduction to his book, recounts in touching language what he went through, the physical and spiritual sorrow, and his dedication to teaching Torah and explaining it to the masses. Indeed, Rabbi Yaakov was a man of dedication. Here is a copy of this introduction, and at the end he details the lineage of his ancestor, the Korban Netanel, the rabbi of Karlsruhe:

One of the famous rabbis of Karlsruhe was the devout rabbi, Rabbi Yosef HaCohen Altman z”l, whose yahrzeit (anniversary of passing) was marked this winter. He passed away after collapsing while delivering a Torah lecture on the mitzvah of visiting the sick in Parshat (the Torah portion) Vayera. See this pamphlet (in HEBREW), which has a great deal to say about the city in general and the yeshiva of the Aruch HaNer in particular:

https://www.hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=58216&pgnum=259

A memorial where the synagogue stood in Karlsruhe

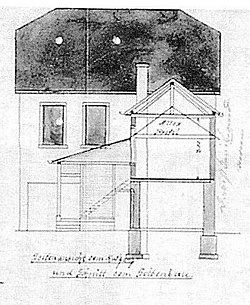

A sketch of the synagogue that was destroyed during Kristallnacht

The New Synagogue which was destroyed on the night of Kristallnacht, 1938

Before the Holocaust, as mentioned, the Nazis had already begun to place restrictions on the Jews of this holy community. The series of decrees was preceded by the expulsion of the Polish Jewish community that had lived in the city since World War I. This community was a shining jewel in the crown of the city and had established a magnificent synagogue there (which was also destroyed during Kristallnacht).

Even before the rise of Nazism, the Jewish community in the area was in the shadow of hostile and antisemitic attitudes from the local population.

The main centre of antisemitic activity was the Technical High School. In 1923, antisemitic leaflets were distributed there, on the occasion of the appointment of two Jewish lecturers. In June of that year, students protested the appointment of chemistry professor Max Mayer from Berlin, as a result of which Max rejected the appointment. The German residents also blamed the Jews for the food shortages; they painted swastikas on the roads, desecrated the synagogues and gravestones. Most of the city’s newspapers condemned the act. In March 1926, Nazis looted Jewish shops in the city and desecrated the synagogue.

With the rise of the Nazi Party to power in 1933, senior party figures conducted an intensified campaign of incitement against the Jews. In 1934, Julius Streicher spoke in Karlsruhe and called for a boycott of Jewish businesses and physical violence against Jews. In September 1935, the campaign of incitement intensified and the persecution intensified. Nazi guards were stationed at the entrances of businesses owned by Jewish residents, who “demonstrated” and in effect prevented customers from entering. The anti-Jewish boycott, which began with the dismissal of Jews from public institutions, became increasingly severe. During 1935, many Jewish merchants were forced to announce that they would not be able to pay their debts.

The Karlsruhe community prepared to deal with the growing material hardship, the boycott, and the persecution. Activities to assist in emigration to Palestine were intensified, and attempts were made by the community to retrain for professional work in areas where it was still possible to engage, such as education and culture.

The deportation of the Jewish residents of Karlsruhe began in 1940. By 1945, 1,280 Jews had been deported from the city, 893 of whom were sent to the Gurs concentration camp in southern France.

In 1933, Karlsruhe had a population of 146,000, of whom over 3,300 were Jews, about 2.1% of the population. In 1939, as the German population in the town grew during the war, the number of Jewish residents decreased, and by 1945 there were only 18 Jews left. Most of the local Jews were murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators.[1]

To read part 1 of the article, please click here.

[1] Wikipedia. See more details on the German Wikipedia.

Since 1933, large numbers of families from the countryside began to move to Karlsruhe, along with emigration to Western countries and increased immigration to pre-state Israel. In 1936, all school-age children were transferred to a separate Jewish school.

At the end of October 1938, as part of the so-called “Polish Aktion”, about 60 Polish Jewish men were deported from Karlsruhe to the border at Zbaszyn (Bentzen), most of them following their families. Many of them subsequently perished in Polish ghettos and camps.

During the November Pogrom, on November 9th-10th, 1938, the synagogue on Kronenstrasse was partially destroyed, and the synagogue on Becker-Friedrich-Strasse was set on fire. Jewish prayer rooms, businesses, and homes were vandalized, and people were beaten by organized mobs. Several hundred Jewish men were taken into “protective custody” and in the following days were deported to the Dachau concentration camp, where they were abused and pressured to emigrate as soon as possible.

Adolf Lebel of Karlsruhe rescued a Torah scroll from the destroyed Kronenstrasse synagogue, dating to around the 13th century in Krautheim, hid it in the attic of the nearby community center, and brought it to the United States when he emigrated in 1945. He later donated the Torah scroll, perhaps the oldest surviving in Baden, to the Sir Isaac and Lady Edith Wolfson Museum in Jerusalem.

On October 22, 1940, in the “Aktion Wagner-Bürkel,” 15 months before the Wannsee Conference, almost 900 men, women and children were taken from their homes and deported by train to the Gurs camp in unoccupied southern France near the Pyrenees mountains. From there, most were later deported to extermination camps in the east and murdered there. More than a third of the city’s pre-war Jewish population, almost 1,100 people, lost their lives in the Holocaust.