Leżajsk, Holy Ground

Travel impressions by Yaakov Rosenfeld, Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

Part 1

A frozen and white town, enveloped in peace and quiet, with dark gray smoke rising from the old chimneys on its roofs. The smell of wood burning in the stoves mixes with the smell of various combustion products, which, together with the freezing, motionless cold, creates a feeling of a Polish winter familiar from old descriptions.

Old, weathered houses, reddish-brown brick chimneys, lace curtains separating the windows of the low-rise houses of Leżajsk from the few passersby, shivering with cold, huddled together by the whispering fire inside. Huddled together by the fire that whispered here for many years, the holy fire of the Rebbe Elimelech, to which holy disciples flocked during his lifetime, and after his death, his burial place was a magnet for tens of thousands of Jews from all over chassidic and fervently Jewish Eastern Europe.

It’s a cold winter in Leżajsk, and I wander among the old houses looking for signs, I check window after window, but there is no trace of the Jewish life that used to be here. The famous town, which was Jewish, chassidic, in its roots. There is no doubt at all that these old houses, in the area of the cemetery and the synagogue, belonged to Jews, and there is no doubt that all these sleepy people with stupidity on their faces inherited these houses and their contents. And yet, my limbs tremble and my heart beats, we are in Leżajsk, it is holy ground!

Years have passed, and the looters are making a handsome profit from the Jews who come to huddle together in the old ohel (small building arround a grave) in Leżajsk. Jews come with heavy packages from all corners of the world, and unload them inside the white ohel, the holy ohel that stands alone on a wooded hill, among the remains of tombstones and graves that remain from a large number of graves that have been destroyed, vandalized, and looted.

In front of the holy grave stands a small caravan that serves as the “ohel hakohanim” (ohel for the priests) who cannot climb to the top of the mountain (as kohanim are not allowed to visit graves aside from those of immediate family members). A long chain marks the ground within which Jews have been buried for centuries, but nothing is visible above it. The Germans used the marble slabs for their own pleasure, and the Polish neighbours were not overly bothered by this fact, just as they were not overly bothered when they saw their Jewish neighbours beaten, tortured, and killed.

In the ohel hakohanim, I met a Jew from Brooklyn, New York. He sat slumped in a corner, his shoulders shaking with tears. He came here alone, without friends or family. He did not come to enjoy himself. He came “to act,” as he put it. After he finished the Book of Psalms, I understood from him that he had left a house full of hardships in Brooklyn. His hardships of all kinds took shape, into a severe and painful heartache which looked the same as that of the Jewish diaspora in every corner of the world.

Livelihood, health, matchmaking, hardships…

Rebbe Elimelech cancels the birthpangs of the Messiah (the hardships prior to the Messiah’s arrival), the fifty-year-old Brooklyn chassid tells me. “Imagine what we would be like without the faith and joy that Rebbe Elimelech, the great spreader of the path of chassidism, “the Rebbe of all the Rabbis” instilled in the Jewish People…

Generation after generation, countless Jews have warmed themselves in the fire of Rebbe Elimelech and his disciples, and the disciples of his disciples. They brought the “livingness,” the strength, and power to Jews in every situation they were in, and now, eighty-five years after the destruction of Poland, Jews from all over the world still come to the little ohel to find solace and comfort.

I saw the Jew the next day and his eyes were shining. I heard him talking to his wife and children in Brooklyn, in a voice full of hope and vitality. The power of the righteous man (the Rebbe), the power of pure faith.

It is quiet and peaceful in Leżajsk. The gentiles who live in the Jewish homes look healthy and calm. An abysmal emptiness is reflected in their eyes that stare at you in amazement as if asking: Why did you come here and what do you want, and we do not try to explain, nor do we care what they think.

We walk around the town on the eve of Shabbat Parshat (the weekly Torah portion) Bo, and try to imagine what it would have looked like here a hundred years ago, on such a Shabbat eve…

Poland is empty and desolate. There is no life in it, no joy of creation, no chassidic melody and Jewish eyes filled with enthusiasm. We walk around the town and come to an exceptionally large building that looks like the White House in the United States. A vast, well-kept plaza surrounds the building, covered in rich and diverse vegetation that is now covered in pure white snow.

The sign on the building tells us that this is where the “Museum of Leżajsk and Surroundings” is located. We are so interested in what the museum has to say about the Jewish town, where on the eve of the outbreak of World War II about half of its inhabitants (6,000) were Jews, and after it, except for those who made the “right mistake” and crossed the San River towards Russia, none of them remained. What does the Leżajsk Museum have to say about the city where Jews were the main artery for its livelihood and joy of life for centuries?

When I entered this museum, I felt sick. Various figures stared at me from the walls and cabinets; strange exhibits, old toys, ancient beer bottles that for some reason serve as objects of historical and museum value.

The man who opened the door for me seemed surprised by the mere fact that people were entering this complex in general, and on a snowy day in particular…

He looked at my Jewish figure, and I thought then, maybe he thinks it would be appropriate for me to be the main exhibit in this museum, because what better way than this figure to express the Leżajsk that was and is no longer?… But the truth is, I have no idea what he thinks or if he thinks, and it shouldn’t concern us either. Without much politeness, I blurted out to him:

“Please show me something about the Jews of Leżajsk.”

“Mmm…” was the spontaneous response of the gentile. And he went into some room to consult with someone or something, and then he asked me for 7 zlotys per person, or eight. There were three of us and we paid.

This man, again humming, “mmmmm,” took out a bunch of keys from somewhere and ordered us to follow him.

We went.

We went up and down stairs, up and down, and from every direction strange figures, terrifying figures, loomed before us. There are glass cabinets and stored inside are military uniforms and swords, and helmets, arrows and spears. The gloomy orange lighting casts terror through the shadows it produces. The place is dominated by what is called in literary parlance “deafening silence,” and the three of us suddenly fear that we are now experiencing an anxiety attack from enclosed spaces, “I wonder if the basic medical insurance we purchased also covers this medical problem”… my friend whispered in horror.

Finally, the mumbling gentile stopped at some corner, and there, inside a glass cabinet, a kind of display case, we suddenly saw things of our own. It was a miracle that we didn’t break the glass in our excitement, because we weren’t far from it…

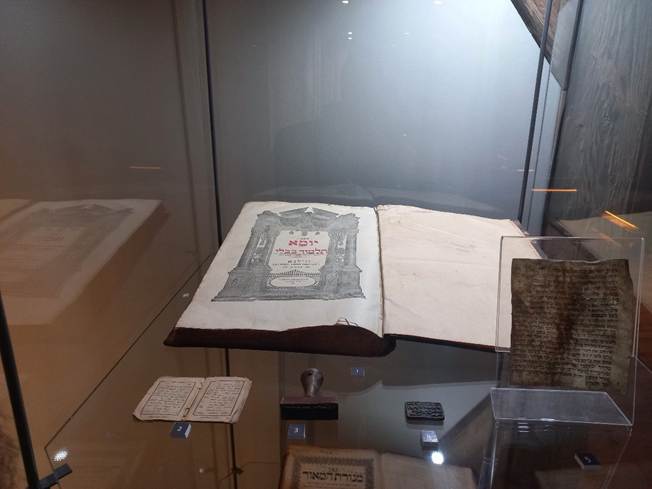

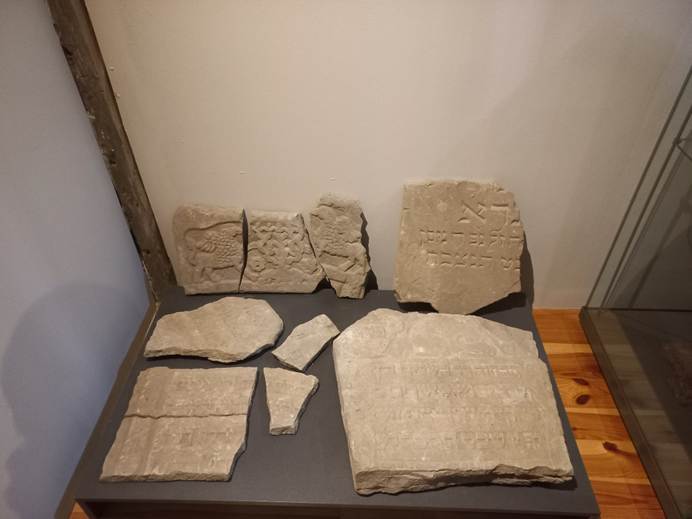

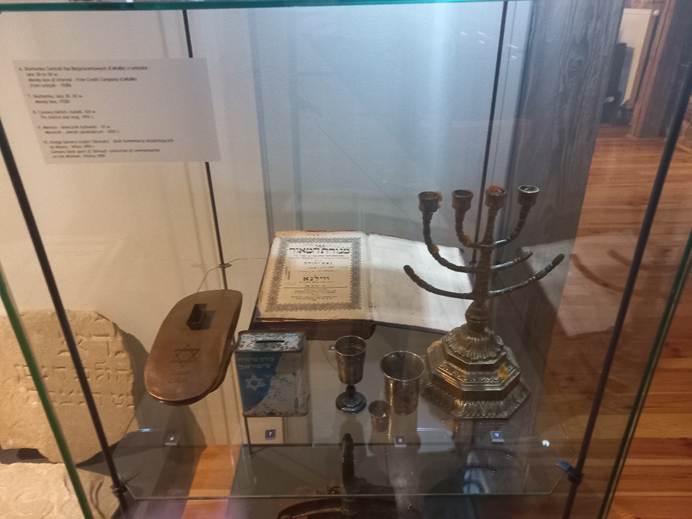

Inside there was a mezuzah, kosher. A wide-open Gemara Yoma, a Babylonian Talmud, published by “The Widow and Re’em brothers,” a small siddur, goblets, a broken synagogue menorah and a manual printing machine. There is also an old, worn-out book “Menorat HaMe’or” book and a few seals and pages, and I wonder, why are these things here, who actually gave the artifacts to the museum?… There was a large, magnificent, and deep-rooted Jewish community here, the murderers came and killed everyone, the Poles came and inherited their homes, the heirs of the Poles came and gave the “archival exhibits” to the museum. How simple, how easy… And on the side, next to the glass cabinet, are arranged fragments of tombstones from the Jewish cemetery. By the way, the yahrzeit (anniversary of passing) of the “dear young man, from upstanding roots” will fall on the 16th of Shvat. Where is the young man buried? Who was he and what became of his family? And why, according to the museum management, are these tombstones located here and not in the cemetery from which they were removed?

“I want to see photos of Jewish life in Leżajsk.”

This is what I said to the aging, mumbling Pole: “I want to see pictures of Jewish life in Leżajsk!”

At the end of the screen, I will present you with the pictures. They are all new to me, I have never seen them. Some are from Leżajsk before the Holocaust and some from the Holocaust era in the town.

The pastoral tranquility of Leżajsk, and of the rest of Poland’s cities and towns, seems never to have been disturbed. But in truth, in 5706 (1945-6), exactly eighty years ago, the peace of the Poles was disturbed.

It was immediately after the liberation, when Jews who had survived the war began to return and tried to search for a memory of what had been their home in the good old days. That same year, the Yiddish writer M. Tzanin toured Poland. The Polish Jewish writer turned around, horrified by what his eyes had seen, and by the fact that in order to stay alive, he had to walk the streets of his homeland under a false name and identity, lest they murder him.

As a “British journalist,” Tzanin arrived in Poland and guarded himself in fear of the Polish population who wandered among the ruins and inherited everything that the Nazi oppressor had left them. Tzanin sat on the trains and listened to the conversations of the ignorant gentiles, and was unable to understand where this hatred came from and what its origin was. They, our Polish heirs, did not have a drop of patience for Holocaust survivors who tried to return home. Everyone was too much for them and they vented their frustration in violence and bloodshed.

I began this journey in the huge city of Warsaw, which is also snowy and frozen, but where, naturally, the necessary pace of life gives a certain vitality and movement that is required, as a capital city. In Warsaw, I discovered a synagogue that surprised me greatly and about which I will write in the next article. The long road from Warsaw to Leżajsk provided me with a lot of food for thought, for about three or four hours of gathering my thoughts and reflecting. On my previous visit to Poland, I focused on Krakow and its northern parts, this time I preferred to feel the historical chassidic warmth without the heirs of the heirs of the Jews to mediate it for me. Incidentally, I am also unable to visit Auschwitz for several reasons, one of which is that I do not need them, they who will mediate for me the traumatic memory that breaks the heart and breaks the soul.

It is a long road, passing through regions and towns that shake the heart and make every part of the body tremble.

The journey from Warsaw to Leżajsk crosses the provinces of Mazovia and Lublin towards southeastern Poland. This region is steeped in a deep chassidic history and geographical landscapes characterized by large rivers and vast plains.

These are the main cities and towns along the route, divided into geographical areas:

Mazovia Province – Vistula River Basin

Leaving Warsaw to the south, the route passes near Poland’s main lifeline, the Wisła River.

Gur (Góra Kalwaria): Located on the left bank of the Wisła.

Kozienice: A town located near the Wisła River, in an area of dense forests (Kozienice Forest).

Lublin Uplands – Wieprz River Basin

Further south, the landscape becomes hillier as you approach the Lublin Uplands and the Wieprz River.

Puławy: A town located on a bend in the Wisła River, it served as an important junction on the way to Lublin.

Kuzmir (Kazimierz Dolny): A picturesque town on the banks of the Wisła, which was a vibrant Jewish center and was known for its unique geographical beauty.

Lublin: The central city of the region, situated on the Bystrzyca River. Lublin was the beating heart of Polish Jewry and a major center of Torah and chassidism.

Southeastern Region (Subcarpathia) – Seine River Basin

Towards the destination, we cross the border into the Podkarpackie region (Lesser Poland), where the San River flows, one of the largest tributaries of the Wisła.

Łańcut: A town very close to Leżajsk, famous for its magnificent synagogue and its connection to many chassidic dynasties in the Galicia region.

Lezhansk (Leżajsk): The final destination. Leżajsk is located in the Seine River Valley. The town was a major Jewish centre for generations thanks to author of the “Noam Elimelech,” Rebbe Elimelech.

That’s all for the first part, hopefully a fascinating sequel will follow in the coming days.

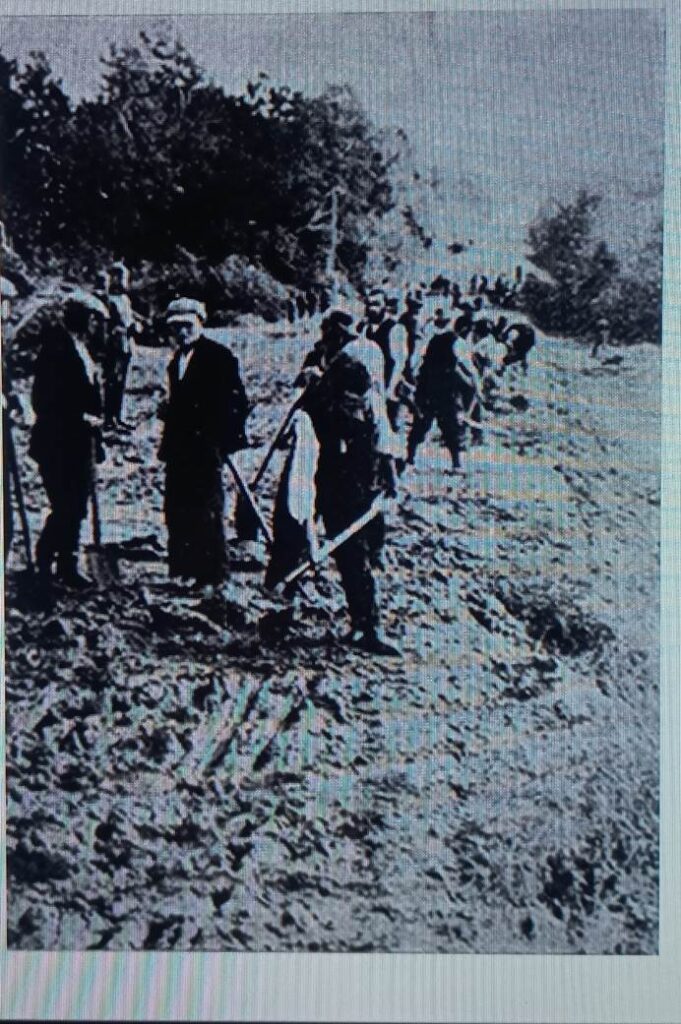

Photos from the town of Leżajsk before and during the Holocaust:

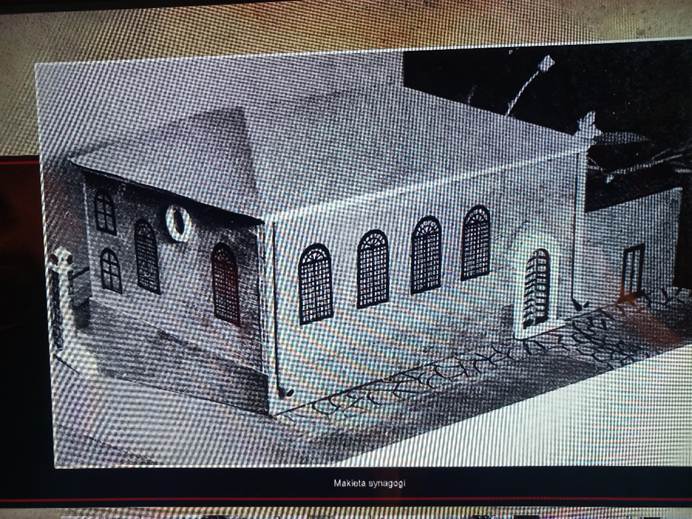

Model of the Leżajsk synagogue, from official documents.

Chassidim in Leżajsk, the eve of the war

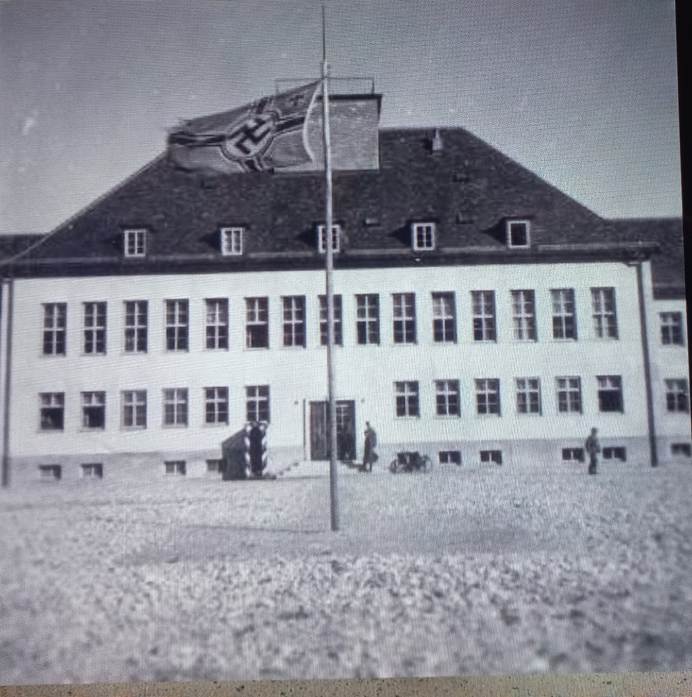

The Nazi flag waving in Leżajsk

Jews in the midst of the war in Leżajsk. Is this forced labour?

The Nazis entering Leżajsk

A Nazi parade in Leżajsk

Forced labour in Leżajsk