Łuków – A Memorial Candle to a Jewish Town that Was and Is No More

By: Yaakov Rosenfeld

Almost none of us have heard of the city of Łuków (pronounced in Polish as Wukov, in Yiddish as Lukov). A magical, Jewish town where Jews lived for eight hundred years and worshipped their Creator with love and innocence, and then descended into the abyss.

Łuków was a chassidic city, pious and full of Torah and fear of G-d, and on the eighty-fifth anniversary of its destruction, we light a candle in memory of the town, it’s holy Jews, and the Jews in it’s surrounding towns.

Jews in Łuków

Oh My Dear Town – An Elegy

Oh my dear town

I will lament for you and be

Greatly sorrowful and bitterly broken over you

For the town of my childhood

How beautiful and pleasant you were during the weekday

And doubly so on your Shabbats and holidays

Before you drank from the poisonous cup

Before your cup of sorrow was filled

And again I see you

In times of peace, simple and pleasant

A life full of holiness and purity

In those days and times

Here is the ancient Beit Midrash (study hall)

With its crumbling walls

Filled with the tears of generations

From broken and shattered Jews

And there, near the Beit Midrash

Oh, how painful and heart-wrenching

My beloved children, they meditated on the Torah

I will burst out in anguish and pain

And in the Ger chassidic synagogue in my city

There they spent nights as days

They endlessly meditated on the Torah of G-d

Those holy and pure

How beautiful and how pleasant it was then

Before your terrible arrival

How did you descend so wonderfully

Down to the depths of the abyss

Came the wicked, the impure, the evil

They killed, murdered without mercy

Who? Old and young, infant and suckling

Those pure victims

(…)

How you faced destruction and intense fear, my town

There is no voice of Torah or prayer

Only silence and desolation will prevail in you

Only horror will entirely cover you

Oh! Who will give me a bird’s wing

I will fly far away until I reach my town

And there I will cry for you day and night

Until my tear runs out

Maybe I will see another survivor there

From the holy and pure people of my town

I will embrace them, I will kiss them with all my strength

Until my soul leaves me

(From an elegy written during the height of the Holocaust in 5704/1943-4 by Yisrael Fikarsh of Pardes Chana, born in Łuków)

“Deserted Hills, Ruins of Life”

After the liberation of Poland, exactly eighty years ago, the writer M. Tzanin toured the cities and towns of Poland and wrote about what he saw. He published the articles in many serials in the Yiddish newspaper Forverts (Forward), and the chapters were later translated into a difficult-to-read book in Hebrew, called “Tel Olam.”

This book, about a hundred communities in Poland, is an important document on the one hand, but heartbreaking on the other. Each chapter is more difficult than the previous one. This collection is a tombstone on the grave of the vast, Torah, chassidic, activist and industrial Jewry of Poland. Precisely because the author wrote in simple language and did not use many literary descriptions, the lines are so poignant and the words, every word, pierce the soul.

At the beginning of the book, Tzanin wrote:

G-d Who is full of mercy, Give me the strength to write down in my poor tongue what my eyes saw and what my heart felt during these wanderings across the hills of desolation and the ruins of a life that seemed to have never existed…

Eighty years have passed since M. Tzanin visited the city of Łuków, which is almost unknown today, but it was a major Jewish community, a city full of sages and writers, and perhaps with an emphasis on writers, since Sofer Stams (religious scribes) filled Łuków and their products were sold all over the world, even in distant America.

Łuków was full of students, chassidim, fathers and sons; generations of the pious and the righteous crowded the streets of Łuków and filled its study halls and synagogues.

Many chassidim lived in Łuków, followers of various rebbes. Rebbes also lived in this city and yeshivas were established there.

Tzanin himself, in another book (in the introduction to “Sefer Łuków”), wrote the following about Łuków:

“The Jewish community in Łuków was the center of terrible killings and cruel torture, not only of the Jews of Łuków but also of other Jewish cities, towns, and villages… Even if all the skies were turned into pages, all the forests into pens, and all the rivers into ink, it would be impossible to write and describe everything that was done in the years 1939–1943 on the soul of Łuków…“

“The German murderers, with their Ukrainian, Lithuanian and Polish assistants, created a hell for the Jews on the soil of Łuków, a situation that pales in comparison to all descriptions of hell…“

For nearly eight hundred years, the town of Łuków was a centre of life and chassidism. The city contained synagogues, study halls, and various societies, such as the Tehillim (Psalms) Society, the Mishnayot (Mishna) Society, the Mikra (Torah) Society, the Baalei Melacha (craftsmen) Society, and the Tiferet Bachurim Society for young men. There were also shtiebels (small synagogues) of chassidic Jews from various sects, yeshivas, and a Talmud Torah school. From all of these places, the melody of Torah study always rang out.

There was a Great Synagogue in Łuków which contained hundreds of worshipers. The synagogue was the splendor of the city. It was painted by the best painters of the city – Hersh Liber and Chaim Metes Mendelbaum. A small beit midrash, in which simple Jews such as carters, butchers and craftsmen prayed, stood next to the synagogue. They were also called “Chevra Mikra.” Every evening between Mincha and Maariv, and on Saturday afternoon, they studied the Chumash (Pentateuch) with R’ Aharon Mikra-rabbi. Also in the Great Synagogue a group of Jews sat every evening around a long table and studied with R’ Efraim Lichtenberg. Several hundred poor children studied in Talmud Torah which was supported by the community.

There was also a new study hall which was called Beit HaMidrash of Chaya Sara, in the name of the righteous Chaya Sara. The rich Jews who prayed there also maintained the building.

A street in Łuków with a synagogue in the background

Synagogues and Institutions

The mayor of Bnei Brak, Rabbi Shimon Siroka z”l, was a native of the city of Łuków, and in his notes he recounted a few memories from the city of his childhood.

“Our city of Łuków was a distinctly religious town. In days gone by, all the city’s residents were observant of the Torah and mitzvahs, and it was natural that all public life centered around the synagogues and houses of prayer.”

“I remember there were three types of houses of worship in Łuków. The synagogue (de shul), old beit bidrash, and several houses of prayer were located in shul-hoyf (synagogue courtyard). In these houses of worship, which have been around since the founding of the city, the worshipers prayed in the Ashkenazi version (the Mitnagdim – opponents of chassidism). The city’s elders who continued the chain of generations, and also many of the townspeople who followed their ancestors ways, concentrated there. The shul and old Beit Midrash were also a place of worship for the city’s rabbis whose names came to fame. In the women’s gallery of these synagogues were the “shtedt” (permanent seats) for all the grandmothers and the city’s honourable women because the small houses of worship didn’t have a women’s gallery.“

“A second type of a house of worship were the chassidic ones, which, in comparison to the shul-hoyf, were a lot younger. The chassidim’s shtieblach (small synagogues) were established in the past century. With the penetration of this movement to the towns of Congress Poland, the chassidic houses of the various rebbes were established one after the other, and their chassidim joined them from time to time. In the course of time, students, important merchants, men of means and fine young men who ate “kest,” meaning, that they were supported by their in-laws so they can devote themselves to study the Torah, concentrated in these shtieblach. Also groups of young men, who studied the Torah and dealt with chassidism, gathered there. The chassidic courts of Gur, Kotzk, Alexander, Porisov, Modzitz. Radzin, Sochatchov, Lublin and others also existed in Łuków. Every holiday, hundreds of townspeople left the city for the Rebbe’s courts to gather around their rabbi and hear his sermon.“

Talmud Torah schools were established in Łuków, as well as a large Bais Yaakov school and yeshivas.

In the yeshiva of Rabbi Getzil Lempiter, which was established in the “Chok” Beit Midrash (the beit midrash where the Chok L’Yisrael book was studied each day), many students studied, and their personalities were shaped by the beliefs of Getzil, who placed his rule over everything.

“In our city also the societies of “Bikur Cholim” (visiting the sick) and “Lechem La’Aniyim” (bread for the poor), which collected donations in various ways and also carried out volunteer activities in these areas, also existed. Of course, apart from these formal societies, the Jewish heart was always open to help others, and there was not a person who felt himself lonely at a time of joy or, G-d forbid, at a time of trouble. The whole town was like one family and a partner in joy or, G-d forbid, in the distress of a city resident.”

Trade and Craftsmanship

In 5670 (1909-1910), Łuków had over 8,000 Jews compared to 3,700 Christians, but the number of Jews decreased during World War I to 6,250 compared to 6,400 Christians. This data is provided by city resident Yechiel Rosenblum in his book of remembrance for his town, and he also provides interesting data on the livelihood situation in Łuków in the interwar period.

41 factories and workshops, 6 hotels, 43 restaurants and tea houses, 137 food stores, 31 meat stores, 19 soda and fruit kiosks, 38 sausage shops, 36 milk and egg stores, 4 wood and coal warehouses, 19 tobacco shops, 6 haberdashery shops, 53 stores selling shoes “and more”, 21 clothing stores, 25 tailor shops, 9 tool and glass shops, 13 hardware stores, 8 bookstores and stationery stores, 6 pharmacies and “medicine warehouses”, 8 petroleum, oil and oil product stores, 10 warehouses for agricultural machinery, sewing machines, furniture and pictures, 5 warehouses for construction machinery. Most of the trade was in the hands of Jews!

And if these figures give the impression that most of the city made its living from trade, Rosenblum continues and provides another list, from the same year, from official publications from the community, of the number of professionals in Łuków:

150 shoemakers, 120 tailors, 45 “leather pattern makers for shoes”, 8 harness makers, 4 furriers, 10 hatters, 4 hat makers (Perhaps the chassidic streimel or spodik hats? -Y.R.), 33 carpenters, 12 wooden building builders, 2 engravers, 4 wooden barrel makers, 17 locksmiths, 25 blacksmiths, 8 tinsmiths, 8 watchmakers, 2 coppersmiths, 30 bakers, 5 cake makers, 23 construction workers, 2 oven makers, 6 painters, 3 upholsterers, 11 hairdressers, 3 bookbinders, 2 photographers (and 4 more craftsmen whose job I could not decipher -Y.R.).

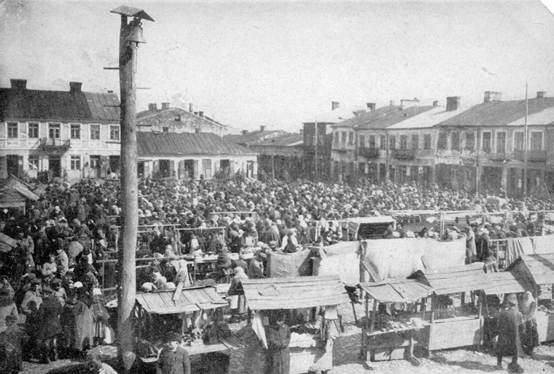

A clothing and shoes market in Łuków

Of all of these, at least 75 percent were Jews! And this was a difficult period for the Jews of Łuków, during which the number of Jewish residents in this city decreased by about thirty percent.

The Łuków market

This is in addition to the many Sofer Stams of the city of Łuków. The city was known for its production of Judaica, Torahs, tefillin (phylacteries), and mezuzahs, which were also sold abroad, and so on.

In the book “Tel Olam”, M. Tzanin tells from his point of view about the boom of craftsmanship in the city of Łuków:

“Łuków was a city of Jewish craftsmen. The Jews of Łuków belonged to various parties and classes of chassidic Jews, but one thing connected them all: work! Eight thousand hardworking Jews, living as they could, lived in the city. In the past, it was a center for shoemakers. Łuków supplied shoes to the peasants of Podlasie. Podlasie is one of the sixteen voivodeships of Poland, located in the northeast of the country, bordering on the north by the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad and Lithuania, on the east by Belarus, on the south by the Lublin Voivodeship, and on the west by the voivodeships of Masovia and Warmia-Masuria.”

“The capital and largest city of Podlasie is Białystok, located in its center. Other large cities are Sowałk and Łomża.”

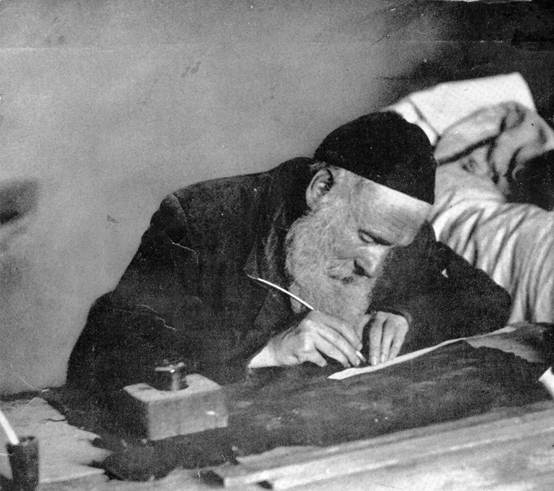

“The Jews of Łuków filled the markets with their goods. When the fashion for nailed shoes passed and the town began to die, the Jews did not despair (…) The Jews of Lukov became sofer stams… [people of different parties and different chassidic groups] all equipped themselves with goose feathers and engaged in writing Torah scrolls, mezuzahs and tefillin. The proletariat of the sofers grew from year to year [and was a significant factor in the socialist revolution, when parties from here and there supposedly mixed the needs and problems of the writers among their many arguments. -Y.R.].”

“But the true and correct path for the proletariat of the Łuków sofers was the path to the entire world: the United States, Argentina, Shanghai, India. The Łuków export of Torah scrolls reached all countries.”

“Łuków was a barometer for Jewish piety in the world. The Jews of Łuków knew how many mezuzahs Johannesburg needed and how many pairs of tefillin Melbourne needed.”

“The Kotzk chassidim, G-d-fearing sofers, would run every morning to dip in the cold mikveh before work…”

Rabbi Moshe Yaakov, a Sofer Stam in Łuków

“As everywhere, with their diligence and loyalty, their skills and their joy of life, they were the spirit of life in the city, and since its destruction eighty years ago, there is nothing in this city. Everything is dead.”

The Jewish writer who walked the smoking ruins of Poland after the war and watered them with tears tells of his meeting with a “Jewish young man” from Łuków who walked around the town with him and showed him “what a face it has today.” “The market was deserted, dead, the former Jewish shops were either closed down, or open as if their owners had fled and abandoned everything. Apparently the town had not changed, and only the eight thousand Jews, the Kotzker chassidim in it, and the proletariat of sofers, were missing…“

The Looting and Sale of the Synagogue

“Even the synagogue is standing, but it is no longer a synagogue. It has become what is called today in Poland a ‘lipa.’ The young man tells me how the synagogue became a lipa. Jews who became lawless were now travelling from city to city and town to town, and selling Jewish houses without heirs or whose heirs have not appeared. They bring false witnesses, conduct false trials, and sell the houses as their private property, which is called in Poland a ‘lipa.’ A house like this that is worth a million gold, these people sell it for three hundred or four hundred thousand gold, and walk away…”

“Thus, much to their shock and sorrow, some of the young people of Łuków lost their senses and sold the synagogue for seventy-five thousand gold. This is exactly the price of five pairs of shoes… The synagogue was bought by the municipality and from now on it will serve as a central warehouse for goods.”

“And the synagogue is not the only building that has become a ‘lipa.’“

“This group of crooks has already sold a third of the houses in Łuków…” (I will spare the description of the nature of the group of crooks and their lifestyle -Y.R.).

The destroyed synagogue in Łuków

Volumes of books will not be enough to describe Łuków and its glory, at its height and in its terrible demise during the Holocaust years, and we, the second, third, fourth and soon also the fifth generation, are duty-bound to at least remember the name and essence of this glorious city, which for years was the home of the great posek (rabbinical decisor) Rabbi Yoel Sirkis z”l. The chroniclers of this holy community never forgot the years that the rabbi served in Łuków, and therefore it should be remembered (even though for some reason this important fact is omitted from various places such as Wikipedia, etc.).

Today, there is a synagogue in Bnei Brak called Lukeveי Volbroz, named after the righteous of the Łuków dynasty. The ohel (building marking the grave of holy people) of the righteous of Łuków, which during World War II was used by the Polish army as an arms depot and then passed into the use of the Nazi army, which destroyed the ohel and completely destroyed the cemetery, was recently revealed through aerial photographs taken by the Nazis, and a new ohel was built in its place.

Nazis abusing a chassidic Jew in Łuków

The Rabbi, a Native of Łuków, who Went with the Children to Sobibor

In this context, it is worth mentioning the wonderful tzaddik (righteous man) Rabbi Menachem Mendel Morgenstern, grandson of the Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch Morgenstern z”l of Łuków (5618 – Shvat 29, 5680/1858 – 1920), author of the book “Ateret Tzvi”. Rabbi Mendel was the son of the Rabbi Moshe Baruch Morgenstern z”l of Łuków, vice head of Agudath Israel in Poland, rabbi of the Jewish community in Poland, who was murdered in Sobibor. Eyewitnesses tell of how Rabbi Mendel who gave his life in order to be with the Jewish children on their final journey to Sobibor, and in his memory, Penina Meizlish dedicated a moving section in her study of rabbis in the Holocaust:

Rabbi Morgenstern did not give up on the children of his city.

“One of the exemplary figures of the Jewish people during the Holocaust is Janusz Korczak, whose devotion to his orphaned children has since become a symbol. But we also know of many other educators in occupied Europe who did not abandon their children and walked with them on the last path. Their heroic deeds have not yet been made public for some reason. The fact that Korczak’s act was not unusual only strengthens the moral value of others who acted like him.“

“One of them is Rabbi Menachem Mendel Morgenstern, the great-grandson of the Rebbe of Kotzk, who was the last rabbi of Włodawa, in central Poland. He was appointed rabbi of the city in early 1939, and was known for his great love of children. With the German occupation, he was taken hostage with nine other Jews, and among other things, he was ordered to hand over all the parts used by the shochets (ritual slaughterers). The Germans justified the order to prevent the kosher slaughter, but it is possible that the real consideration was to neutralize the Jews with cold weapons (weapons without ammunition). In August 1942, the Germans decided on the children’s aktion (roundup). Since the Jews did everything possible to avoid it, the Germans resorted to cunning methods, and managed to gather most of the children to the sports field, ostensibly for a health check. Rabbi Morgenstern also appeared there. Nitschke, the head of the Gestapo in the city, wanted to release him, claiming that his turn had not yet come, but the rabbi refused and stayed put.“

“His presence calmed the children, and together with them and his children he went to Sobibor. This matter appears in the same memorial book in different versions, so there is no uniformity regarding the number of children who were there, but from comparing the testimonies it seems that there were more than a hundred. In my opinion, the multitude of versions actually testifies to the truth of the act, which came up after the war in the trial held in Hanover of Nitschke and his group.“

“So far, I have not been able to find any additional source to complete the documentation on this matter, but there is no doubt that at the heart of Rabbi Morgenstern’s decision to go with the children of his city, and thus forgo the temporary opportunity given to him to be saved, was the leader’s sense of responsibility and commitment to his community, as he understood it in those difficult days.“

(Penina Meizlish, Rabanim BaShoah, Sinai 116, 5755, Daat)