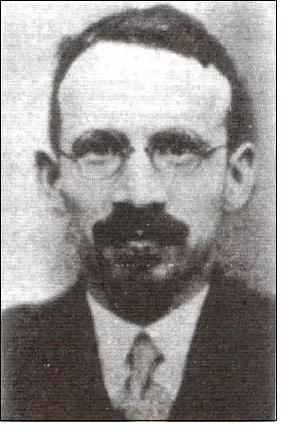

Rabbi Avraham Shlomo Levison z”l

One of the important rabbis of Holland, nicknamed “Rabbi Simcha” (happiness) even though his name was never Simcha…

Written in memory of the revered rabbi who perished in the “Lost Train”, on the 12th of Iyar 5705 (April 25, 1945).

By: Yaakov Rosenfeld, Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

Rabbi Avraham Shlomo was born in 5662 (1902). He was a G-d-fearing and exceptional Torah scholar who, in his youth, was already able to teach, and in the year 5695 (1934-5) he was appointed to serve as the rabbi of the city of Leeuwarden and the chief rabbi of the entire district of Friesland. At the same time, he also served as the rabbi of the district of Drenthe. These places were all in Holland.

Leeuwarden, an ancient city, had no Jews left after the Holocaust. Righteous Among the Nations preserved the ancient synagogue from destruction. Later his furniture and all its contents were moved to Israel, where they were installed in the synagogue in Kfar Batya in the Sharon region.

In 5698-5699 (1938-1939), Jews who had fled Germany to Holland were housed in the town of Westerbork, which was within Rabbi Levison’s rabbinate. It was at this time that the rabbi’s leadership was revealed in all its glory, nobility, and mercy. He would stay with the refugees, on Saturdays and holidays, and at all times of fasting, and would accommodate them as much as he could. In the camp, the rabbi was called “Rabbi Simcha”, because when he came to the refugees with his huge and compassionate heart, he would bring them rivers of joy and serenity.

Rabbi Levison was a pious religious person, but he accepted every individual, regardless of who he was, and he sprinkled the brokenhearted with dews of revival.

After the German occupation, he quickly rescued 700 refugee families from the camp and housed them in houses throughout his city, but their peace did not last long because after about a month the Jews were deported back to the same place, which was converted into a concentration camp.

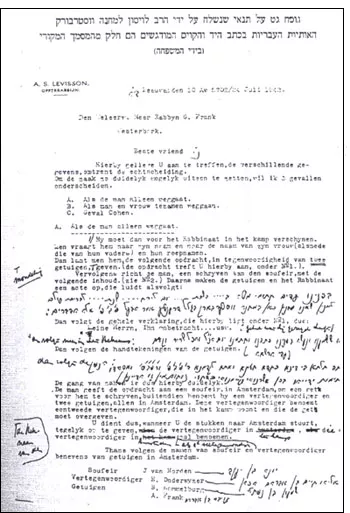

As chief rabbi he was given authority, and for a long period of time he faithfully served the residents of the camp. He took care of them like a compassionate father and provided for all their needs. At that time, a lot of people wrote asking to free agunot (allowing a woman who does not know the fate of her husband to remarry).

Getts (Jewish divorce documents) that the rabbi wrote for the camp residents are preserved in London.

In 5703 (1943) he was himself deported to the camp, and from there to Bergen-Belsen.

He represented fear of Heaven and supreme holiness. He refused to eat non-kosher food even when he was weak and his life was in danger.

In an answer he wrote in the summer of 5702 (1942) to one of the rabbis of The Hague regarding a transfer of bodies from a mass grave to burial in a cemetery, he wrote not to bury the victims in coffins and not to perform the purification, rather to bury in shrouds only.

In one of the testimonies about the Seder night in which the rabbi participated, it is said that he gave his potato to his elderly father. When asked what he would eat, he replied: “It’s not worth talking about, father has never eaten non-kosher food in his life. Will I be able to see him in his old age eating chametz (leaven) on Passover?” And he, the son, said he would eat chametz without having a choice. Apparently he participated in the composition of the special prayer that accompanied the eating of chametz on Passover.

Abel Herzberg, who was among those who documented life in Bergen-Belsen, testified about him: ” Rabbi Levison of Leeuwarden was a hero, who refused to eat a pig even though he was dying of starvation.”

Unfortunately, after the rabbi devoted so much of himself to the People of Israel during the difficult years, he met his death from physical and mental agony and torture, just before the liberation on the train known now as “The Lost Train.”

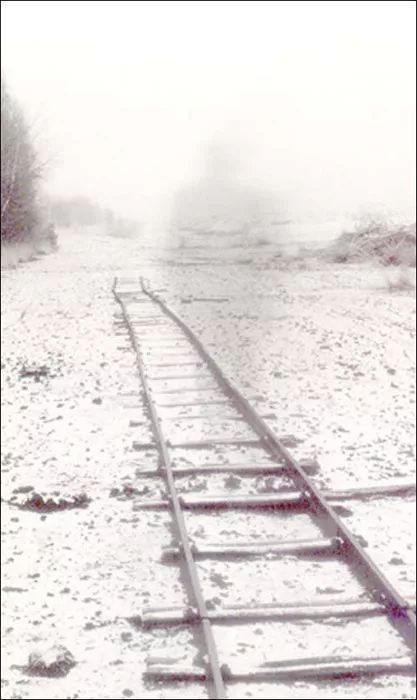

The broken train tracks where the Lost Train stopped, courtesy of Yad Vashem

The Lost Train

In the month of Iyar 5705 (spring 1945), a few days before the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen camp by the British army on April 15, 1945, the camp commander Josef Kramer decided to send all the Jews who were in the camp to the gas chambers in Theresienstadt. Beginning in January 1945, 3,724 Dutch Jews were concentrated in the “Sternlager” (Star Camp) for the purposes of Himmler’s “exchange program”. About 2,000 of them were considered “privileged” because they had certificates or submitted applications for certificates or visas to other countries. Kramer ordered the SS to send about 7,000 Jewish prisoners on three trains to Theresienstadt. The first train left Bergen-Belsen on April 6, 1945 and had 400 prisoners from the “Sternlager” and 2,100 other prisoners on it. The train was liberated on April 13, 1945 by the Americans in the city of Farsleben. The second train left Bergen-Belsen on April 7, 1945 and arrived in Theresienstadt. The third train left Bergen-Belsen on April 10, 1945 and carried about 2,500 Jews from the Netherlands, some from the “Sternlager”, as well as Jews from Hungary and Yugoslavia. The train arrived in Trebitz but not at its destination, later it became known as the “Lost Train” or the “Lost Transport”.

The Story of the Train

The Germans crammed the Jewish prisoners into cattle cars and coal cars. Most of them were sick with typhus, tuberculosis, or other diseases and suffered from hunger and exhaustion. The train began a difficult journey that lasted 13 days. It traveled in the direction of East Germany and looked for railway routes had not been bombed by the Allied Forces, and were not in the occupied areas, in order to reach the south, to the area of Prague and Theresienstadt. Even after the Bergen-Belsen camp was liberated on April 15th by the British, the train remained under the control of the SS and continued to travel. The train was caught in an exchange of fire between the German military and the Red Army, and was subject to aerial bombardment by the Allies.

Apparently the train supervisors were embarrassed and didn’t know where to go. The English advanced from the west, the Americans from the south, and the Russians approached from the east. The Americans bombed railroads and bridges from the air, and this meant that “our” train was stopped many times.

(Yona Emmanuel, It Will Be Told To Generations, pg. 166)

During the journey, many prisoners died. Every time the train stopped, the Germans allowed the Jews to take the dead off the cars and bury them on the side of the tracks. Some of the Jews who got off also tried to look for food in the fields next to the train. There were two lawyers on the train, Dutch Jews, Yitzhak de Vries and Yosef Weiss, who made lists of everyone who died on the way and at which station along the journey his body was taken out and buried, and noted the waymarks on the train tracks. The day before the end of the journey, the German soldiers fled the train and the Jews were left to fend for themselves. On April 23, 1945, the train entered a dense forest in eastern Germany and was stopped outside the village of Trebitz by Russian soldiers from Marshal Zhukov’s army, and they liberated the Jewish survivors.

According to a source cited in English on Wikipedia: “The guards gradually abandoned the prisoners as the Allied Forces approached, leaving the Russians to discover a train car full of the bodies of the dead and others about to die, with a few more prisoners seeking shelter in abandoned houses nearby. Of the prisoners, 198 had already died of malnutrition and disease; Another 320 would die due to complications from exhaustion and disease. Some of the survivors reported that some Soviets who rescued them raped many of them…”

Eight weeks passed before the typhus epidemic stopped. By then another 320 men, women, and children had died. The last to die in the transport, Clara Miller from Holland, was buried on June 21, 1945 in the Jewish cemetery.

Two prisoners, Menachem and Miriam Finkhoff, who survived the transport, left Trebitz on May 13, 1945 on bicycles in order to return to the Holland. Even before they crossed the Dutch border on June 9, 1945, they gave the Americans a memorandum for the Foreign Office at The Hague on May 18, 1945 in Delitzsch, Saxony, reporting on the third train and the condition of the passengers. Through them, the Western Allies learned about the “Lost Transport” from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. American liaison officers contacted the Soviet military offices and they traveled to Trebitz to check the veracity of the reports and initiate the repatriation of the survivors. On June 16, 1945, before the end of the four-week quarantine, the repatriation of the survivors to their country began.

Among the survivors of the “Lost Train” are famous Jews, including Hanna Goslar, who passed away this year and has already been written about on the Ganzach Kiddush Hashem website (in Hebrew).

(Sources: Wikipedia, books, commemorative websites)

Today, on the yahrzeit (anniversary of death) of the revered rabbi, we will unite with the memory of Rabbi Avraham Shlomo ben (son of) Rabbi Shabtai, and perhaps we will also remember him by his second name, “Rabbi Simcha”… and we will pray for the uplifting of the soul of the rabbi who gave all of himself for the suffering and downtrodden People of Israel, and he, just before the light emerged, was not able to see the end and died from pain and torture.

“For you will see the land from afar and you will not enter it…” (Deuteronomy 32:52)

In a future article, we will G-d willing published the names and actions of more survivors and victims.