The Gemara that was Translated in the Cellar

A special article in honour of 80 years since the start of an amazing project

By: Yaakov Rosenfeld

In the month of Av 5783 (summer 2023), about three months from now, it will be the fortieth anniversary of the passing of Rabbi Shmuel Hibner z”l, who for most of his days served as the rabbi of the “Skola” congregation in Brooklyn, New York.

Perhaps it would have been worthwhile to dedicate a separate page to the man and his work then, around the day of his 40th yahrseit (anniversary of death), but “who can withold words?” (Job 4:2) now, at the eightieth anniversary of those dark and deadly days when Rabbi Hibner sat in hiding in occupied Belgium and engaged in his life’s work: translating the Shas (all 6 orders of the Mishna) into the Yiddish language.

Our generation is influenced today by Shas translations into various languages, in magnificent editions, which are published with the generous assistance of various philanthropic personalities and bodies, but that spring, in the year 5703 (1943), exactly eighty years ago, there sat a Jew, a clear Torah scholar, secretly, in the dark, And he was busy translating the Shas into Yiddish. Can anyone imagine what enormous mental effort was required of him to do this?

Let us go back, eighty years, and enter a dark cellar, under the house of a Belgian barber in Brussels, where a Jew sits in the dark, together with his wife. There was dark in the cellar and constant fear in their hearts. Who knew if the Belgian barber would keep his word and not expose those hiding in his house to the Gestapo? And maybe just like that, the wicked would discover the hiding place, and then their religion…

Their only four-year-old son was handed over six months prior to a gentile family. They themselves, after moving to Vienna from their native Galicia (in more detail: From Nadvorna, the famous town), miraculously managed to escape to Belgium, this after Shmuel himself almost met his death on Kristallnacht and was saved thanks to his past service in the Austrian army.

From Vienna they fled to Belgium, and there, in Brussels, as mentioned, they found a hiding place, from which the rabbi almost never left, after he was almost caught during the only time he tried to leave.

In the preface to his halachic (Jewish law) book that he published many years later, when he served as a rabbi in the United States, he wrote words of praise and glory about his wife “the faithful Yachet, whose eyes were always open to protect me from any harm… In the days of darkness and danger, I was not allowed to come out of my hiding place and she risked her life and went out to buy a loaf of bread…”

In that episode, a prominent Jew named Netanel Levkowitz was walking around Brussels. He, who lost those dear to him in Warsaw, walked around Brussels with a burning feeling that the study of the Shas must be made accessible to the younger generation who have no teachers and educators, now in the days when the world was being destroyed. Netanel was ready to pay all he had and bear all the burdens and responsibilities to fulfill his desired goal.

And so, in an indirect way, Divine Providence led Netanel Levkowitz and Rabbi Shmuel Hibner to meet.

It was exactly eighty years ago, in the spring of 5703 (1943).

It is indescribable how much dedication was required on the part of the two men to begin such a project in those days when the sword of the angel of death hovered over them and reaped endless victims.

And so, in a dark cellar in Brussels Rabbi Shmuel Hibner sat and translated three tractates: Brachot, Bava Metzia and part of Bava Kama (after the end of the war he added and translated the tracts of Bava Batra, Shabbat, and the rest of Bava Kama).

Every week, on Sundays when the Nazis drank until they were drunk, Rabbi Shmuel would meet with Netanel, hand over the material and move on. Sometimes, Rabbi Meir Fierwaker, author of the book “Mekadshei Yisrael” (on which it is appropriate to devote an extensive page, an idea for another time) would also join the meeting, and he contributed with his experience and wisdom.

The decision to translate the aforementioned tractates was made unanimously because “the translation is intended first and foremost for the students”… (and these tractates are commonly studying by students)

Later, when the writer Tovia Preschel described the project and its creators (Remembrance Compilation, Part 2), he marveled at the magnitude of the spiritual incentive of these righteous men and wrote:

“At a time when the Nazis were taking the young students from all over Europe to the crematoria and the gas chambers, Jews are sitting with the sword of the Germans placed on their necks and preparing textbooks for youth in the deserted ‘cheders’ and Talmud Torah schools…”

“They did not dream of the future, and they would not have vowed that if they stayed alive they would take up the matter. Instead, they immediately approached the carried it out while everything around them was upside down and there was the fear of death.”

“This is not a legend but a wonderful story about Jewish tenacity, about Jewish faith, about an intense love for the Talmud, a great love that streams of blood will not extinguish…”

Netanel Levkowitz, a merchant and businessman, was the descendant of the Maharal (Rabbi Yehuda Loew) of Prague. He conceived the plan for the translation of the Shas in his heart many years before, and in the month of Elul 5704 (summer 1944), when Belgium was liberated by the Allied armies, Levkowitz and Hibner met again and prepared the three volumes for printing. Three volumes written in blood and with great love, love of God and love of the Torah.

The volumes were printed with splendor and magnificence. Levkowitz spared no effort and spent a great deal of money on his life’s work. Later, when he printed a particularly fancy edition in Belgium of the tractate Bava Metzia, in 5721 (1961), the volume won a special award from the Belgian government for it’s beautiful printing.

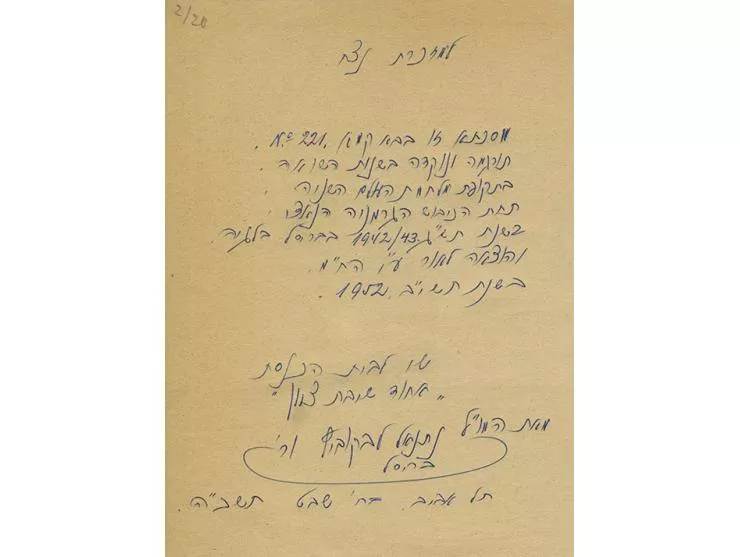

The dedication of Rabbi Netanel Levkowitz for the volume he donated to the Ichud Shivat Zion synagogue in Tel Aviv.

In 5707 (1947), Rabbi Shmuel Hibner immigrated to the United States and was appointed rabbi of the “Ein Yaakov” synagogue of the Skola group in Brooklyn.

Skola (In Yiddish: Skoleh or Skolieh; in Polish: Skole; In Ukrainian: Ско́ле) is a city in the region of Lvov, now in eastern Ukraine, where a large Jewish community existed prewar. The town is immortalized in the last name Skulski (according to Wikipedia).

In the United States, Rabbi Shmuel prevailed in learning the Torah and spreading it. He meritted to derive joy from his descendsants and his halachic (Jewish law) book was decorated with the rare and enthusiastic approbations of Rabbi Moshe Feinstein and Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach.