The Holy Rabbi Yosef Feiner Z”L of Lodz, May G-d Avenge His Blood

Eighty years since his death in sanctification of G-d’s Name

By: Yaakov Rosenfeld, Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

80 years since the liquidation of the Lodz Ghetto

Eighty years have passed since the liquidation of the Lodz Ghetto, and we at Ganzach Kiddush Hashem have produced a two volume book on the Jews of Lodz and their destruction.

At the end of the Jewish year, in the end of Elul 5784 (2024), on the eightieth anniversary of the murder of Rabbi Yosef Feiner, may G-d avenge his blood, who was one of the greatest rabbis of Poland in the interwar period, we spoke about this exhalted and holy tzaddik (righteous person), whose name is almost unknown today. And if the sages said very great things about Torah scholars who were not eulogized properly, what would have been said about a wonderful genius and an exhalted righteous man who was not eulogized at all?

Rabbi Feiner in the Lodz Ghetto, third from left

Therefore, during the twilight of the year 5784, I collected a little material about the genius and righteous man, and for various reasons it was decided to publish it after the holidays, and in the meantime, through Divine Intervention, I found a fascinating document in the Yad Yaari archive containing an exerpt from a conversation between the German writer, Friedrich Hilscher, and Rabbi Yosef Feiner, during those evil days, in the midst of the dying ghetto.

Hilscher, who after the Holocaust described himself as a staunch opponent of the Nazi Party and its ideas, managed to enter the ghetto under a cover story that earned the trust of the SS leadership. He met with the “Ghetto Emperor,” Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski; with the Ghetto Police Chief, Leon Rosenblatt; and with Rabbi Yosseleh (Rabbi Yosef Feiner). In his book “Fifty Years with Germans,” he writes about that conversation and gives over its exact details.

The story that he gave in order to enter the ghetto and strike up a conversation with anyone he wanted was that he was conducting research, so to speak, about the traditional Jewish drink “mead” (honey water).

Indeed, the first part of his conversation with Rabbi Yosef Feiner (who in Hirschler’s writings is referred to as the rabbi who heads the “Community of Rabbis near the Elder of the Jews in Litzmanstadt,” which had 15 rabbis as members) revolves around the matter of honey water, but what follows is much more fascinating. Philosophical conversations of faith in the Valley of Tears, between a German writer and one of the greatest Torah scholars of that generation.

Rabbi Yosef Feiner, on the right

Here are some quotes from the conversation (the wording has been editing a bit – Y.R.):

Rabbi Feiner could be seen in the doorway, wearing a hat, and he removed it. Remembering that the gentile might be offened, he put it back on (…)

“You need to speak with me?” opened the Rabbi.

I explained to him that I want to ask him about the meaning of the drink mead in the service of G-d.

In his answer Rabbi Feiner confirmed that the mead was adopted by the Jews in medieval Germany because they saw it as a noble drink. They drink it on Rosh Hashanah and on (the eve or at the end of) Yom Kippur.

The rabbi offered to bring me the prescription, but I politely declined his offer (because then the possibility of coming back to the ghetto would have been closed for me).

I asked the rabbi:

One day the Christian persecution of the Jews will stop. Now the Nazis began to persecute the Christians as well.

The rabbi said: Like we are being persecuted?

I asked the rabbi: When will G-d put an end to the matter?

The rabbi spread his hands upwards.

I asked: How does God allow nations to desecrate His holy Name like this, and if he didn’t want it, it wouldn’t have happened.

The rabbi answered the question: Do you not believe in the man’s free choice and will?

I answered: (…) He does not have free will. What is your opinion?

The rabbi said: Do you mean to say that wickedness is always permitted?

I answered: That’s not what I said.

(there are several incomprehensible lines here – Y.R.)

The rabbi: I will give you a lesson for beginners:

The soul

(Hilscher wrote it in the dialect, “neshume” – the soul, in the chassidic pronounciation, and indeed in his writings elsewhere he wonders about the differences in pronunciation between the German Jews he knew and the chassidim in Poland. He also spells the word “guf” – body – as Rabbi Feiner pronounced it, “gif,” while the word “ruach” – spirit – is spelled “ri’ech.”)

It is a divine portion given to man as a deposit only.

And it returns to God.

But the spirit (ri’ech) does not return, because it stands before G-d as having freedom of choice and having two passions,

The good and the bad,

And after its death it is given its eternal reward or punishment.

The soul is whole, and so is the body.

This is how we combine the devotion of the soul to G-d through Chassidism with the strict laws imposed on the human spirit, according to the faithful…

(I do not know if the writer quotes the rabbi’s words verbatim, and therefore I do not feel it is appropriate to explain the meaning of his words – Y.R.)

I told him: the apprentice expresses gratitude.

The rabbi said: and what did you learn?

Rosenblatt (the chief of police) made a threatening gesture towards the rabbi with his finger, but Hilscher responded: The rabbi has the right to ask like that, and I am honored that he considers me that way.

Later Hilscher continues describing this dialogue with the rabbi, and finally asked the rabbi for a blessing:

I held the rabbi’s hand and asked for a blessing.

I told him: I am ashamed of everything that was done here, by Germans, in the name of Germany.

But I can only do very little.

My friends and I resist, as much as we can resist, but what are all these things (worth)?

I blessed him: Good fortune and blessing for a hundred years, the way old Lederman blessed my grandmother.

And he answered me: and I will bless you with this blessing itself.

I was happy, my face lit up and we all laughed.

Rosenblatt said: Who knows when we last heard laughter here?…

I said to the rabbi: You have given me great happiness, and we parted with repeated bows.

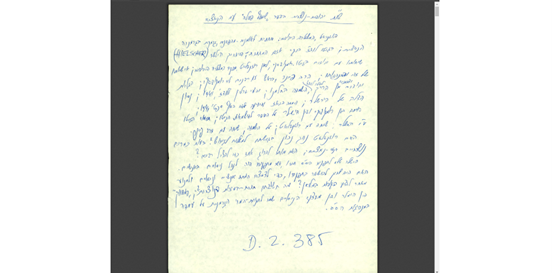

A copy of the original, Yad Yaari archive

Strength and Might for the People

Rabbi Yosef Feiner served in the Lodz rabbinate for over 40 years.

In the Lodz ghetto he was loved and admired by all, and this situation will prove it:

A large group of workers in the Lodz ghetto decided on a strike against Rumkowski, the ghetto “emperor.” They were desperate and starving, and they had nothing left to lose.

Rabbi Yosseleh knew that this organization could lead to bloodshed, so he himself came to participate in the secret meeting of the workers.

He delivered an emotional speech, and miraculously, his words entered their hearts and the strike was canceled, because his words came from the pure heart of a revered leader whom they all loved and were meticulous to follow. And these were his words in that gathering:

“Gentlemen, G-d have mercy on us! We Jews are powerless! I do not think of such a thought to rebel against the Nazi rule. We are not capable of that. But we have the power of trust (in G-d), the power of prayer, the power of our holy Torah.”

“Everywhere I happen to be, I notice, hear, and see that they disgrace and abuse, trample on everything sacred. Jews forget that only G-d can help us. Sometimes brothers become rude and cruel to each other. We lack the desire to help others, if G-d forbid it continues like this, we will all perish! Jews! Only with true trust in G-d, only in upstandingness, in righteousness, and with kindness will we endure and overcome the enemy!”

(Zachor, file 7, Alexander Yizkor Book)

“The Jews of the Lodz Ghetto knew to tell that with his moral influence, he more than once restrained the King of the Jews, Rumkowski, and prevented many decrees. I was privileged to see Rabbi Yosseleh for the last time in the Lodz Ghetto in the summer of 5703 (1943). I was shocked by his appearance. Instead of the handsome Rabbi Yosseleh with the patriarchal beard, which inspires awe, I sat opposite a shrunken old man without the signature beard, lacking title and splendour… Only his two good eyes smiled at me, from a good heart. I almost burst into tears at his poor appearance, although he comforted and encouraged me. I sat in his midst for a long time that Shabbat. Encouraged by his words, I returned to the ‘ghetto prison,’ reconciled and calm, his words of encouragement had a great impact on me and gave me confidence for a long time.”

(Shlomo Frank, Tagbuch Fun Lodzer Ghetta, Alexander Yizkor Book)

Rabbi Yosef Feiner, may G-d avenge his blood, was loved and admired by both the Jews and the Polish residents, whose noble character inspired respect and admiration. He went in and out of government and military circles, with his long, heavy beard falling over his polished rabbinic garb.

Rabbi Yosseleh was born in Piotrkow in 5627 (1867), the firstborn to a family that made a living in physical labour. He spent his childhood in the town of Opoczno, which is close to his hometown and where there was a significant Jewish settlement. As a child, he studied Torah diligently and with great desire, even under difficult conditions. He studied Torah in Piotrkow, in the Lodz region. He excelled in his studies, debated with the city’s scholars and assisted the city’s rabbi from whom he learned Torah. At a young age, he was ordained by him as a rabbi. He learned sand studied quickly and passed the matriculation exams. After his marriage to the daughter of Rabbi Moshe Chaim Buchian of Lodz, he continued his sacred studies at his father-in-law’s house, and in particular he excelled in the teaching of issur v’heter (prohibitions and permissibility) and the laws of Choshen Mishpat (the last section of the Code of Jewish Law, dealing with judicial procedures, damages, injury, and more). He was honored and became a guest of the house of the chief rabbi, Rabbi Eliyahu Chaim Meisel, from whom he received his rabbinical education. Rabbi Meisel noticed that this young man was destined for greatness, nurtured him, and became very close to him, until Rabbi Yosseleh became his right-hand-man in teaching and leadership.

A year after his marriage, he served as a “Rav Mitaam” (community rabbi connected to the government) in nearby Alexander, and was a Alexander chassid. After a year and a half, he left and became Rabbi Meisel’s chief assistant in Lodz, in matters of Torah law, in appearances in government courts, and in contact with the authorities. He strove greatly for the common good. In all his many trips for public affairs, he took with him a small volume of Choshen Mishpat and repeated its teachings countless times.

Due to his refined manners, his intelligence and nobility, his mastery of the Polish language and other languages, which he learned on his own, he had great influence in government circles, until he was appointed in charge of the army in the Lodz district as a military rabbi with the rank of lieutenant colonel. The rabbi took on this role to take great care of the Jewish soldiers, and even saved Jewish soldiers from severe punishment and death. During the days of the Pogrom in Chisinau and the days of the Japanese War and the Revolution, he worked to secure the lives and property of the Jews of Lodz and took part in organizing the Jews of Lodz to defend themselves with arms.

After the death of Rabbi Eliyahu Chaim, Lodz remained without a rabbi for a long time. The local rabbinate established a committee of important rabbis, and Rabbi Yosef was one of the most prominent of them.

During the First World War, he took care of the Jewish refugees who came to the city following the battles that took place in the area and also helped the Poles who turned to him. He turned to the German occupation authorities, and due to his respect and trust, managed to save many Jewish lives.

He was a kind man, and was ready to give his life for each and every person. The Jews of Lodz knew that you could always go to Rabbi Yosseleh, and even on Seder night they would come to him with dozens of questions about Passover.

Immediately after the occupation of Lodz, the Germans began humiliating and oppressing the Jews. The members of the government-in-exile, who fled to the east when the war broke out, wanted to smuggle the rabbi out and put a car at his disposal, but he refused to accept their offer, because he did not want to leave the members of his community, whom he had served for over forty years. He was transferred to the ghetto together with 160 thousand Jews of Lodz and suffered the torments of hell with them.

Following the move of Rabbi Dr. Simcha Triestman from Lodz to Warsaw, on Shvat 26, 5701 (27/2/1941), until the great deportation that took place in 5702 (9/1942), Rabbi Feiner headed the Committee of Rabbis in the Lodz ghetto, which worked in coordination with the Judenrat, and included about 15 rabbis. The committee was included in the Registry Department; it dealt with matters of engagement, divorce, births, and deaths. The committee worked in close organizational connection with the Department of Marriage Affairs. The rabbis, the members of the committee, were paid the same as the other officials of the administration. The chairman and the heads of the administration extended their patronage to the rabbis and other clergy in the ghetto, registering them fictitiously as administrative employees. The members of the committee published the decision allowing mothers and people who felt that their strength ws running out to eat non-kosher meat, after consulting with a doctor and a rabbi.

When the situation in the Lodz ghetto worsened and the Nazis were hunting for the rabbis, Rabbi Yosef hid in the old cemetery. In the month of Elul 5704 (Aug.-Sept. 1944), he was caught and executed in sanctification of G-d’s Name.

(Rabbanim Shehnispu BaShoah, Sefer Kehilat Piotrkow, Carmeno Y., and more)