By: Yaakov Rosenfeld, Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

“Even my wisdom stood before me,” said Rabbi Chanina Bar Papa: Torah that I learned in ‘af’ was fulfilled for me” (interpretation: the Torah that was fulfilled in me is the same Torah that was learned in “af” – through suffering, sorrow and difficulty).

It was the year 5707 (1947) in Jerusalem.

Yaakov Tzvi stood behind the door and his weak fingers knocked lightly.

He had been through a lot before he got there, and now his heart was beating, reverberating, much louder than his hesitant knocks on the door.

Yaakov Tzvi, a Holocaust refugee, made his way to the yeshiva head’s room with failing steps. He’d been through it all, he’d seen it all. Circumstances taught him not to fear anything in the world. He saw death before his eyes more than once or twice. But now, precisely here in the land of dreams, he was afraid. Trembling with fear.

The thought went through his head: “And what if they do not accept me to the yeshiva?”

Around him he saw cheerful young men, his own age, young men who have a home, a father and a mother, young men who have not spent the last six years under siege and in distress, facing hard labor and murderous beatings, young men who haven’t experienced bereavement and despair. They went the usual route, like every child and teenager on earth.

They, the young men who ran around him, would naturally study in the yeshiva. But he, Yaakov Zvi son of Avraham Chaim, may G-d avenge his blood, who did not study in the seventh grade, nor in the eighth grade, nor in the ninth grade, nor in yeshiva, why would they accept him here in the yeshiva meant for older students? It was likely – so he pondered – that all this effort was in vain.

The waiting seemed like forever for him. It is doubtful whether in that long line, when his life depended on being sent to the right or left, whether he felt such tension. Then his senses were clouded and he did not expect anything as he was not afraid of anything, but now, if after all this, he, the survivor of the high-quality and Torah-oriented family, would not accepted into the yeshiva, he might stay on the street and become an ignoramous in matters of religion. Yaakov Tzvi could not think of such an idea happening.

The young man sat in front of the head of the Yeshiva in a small room whose walls were lined with iron cabinets and had a three-winged fan hang from the ceiling.

The head of the yeshiva did not know the young man, but what was clear to him is that he did not belong there. Not “with us”. He heard that a Holocaust survivor had filled out a registration form. He has no doubt that in terms of his educational level, the boy had nothing to look for in this excellent yeshiva, and the only question was how to explain it to him nicely without insulting the orphan boy who had already been through enough in life.

To sum up the dilemma that tormented the head of the yeshiva in a short sentence, it could be said like this: how can one not harm the young man who was a Holocaust survivor while also not harming the reputation of the yeshiva?

The head of the yeshiva looked into Yaakov Tzvi’s big eyes. He mistakenly recognized sadness and despair in them, mourning and gloomy grief. I can’t bring him in here, but what do I say to him, for God’s sake?

I don’t have the tools to deal with such a broken soul. And in general, it is doubtful that the young man ever studied a whole page of Gemara. What exactly is he going to do here in the yeshiva?

A long silence reigned in the small room. The head of the yeshiva knew that it was no longer possible to continue this silence. We have to finish the conversation and the sooner the better.

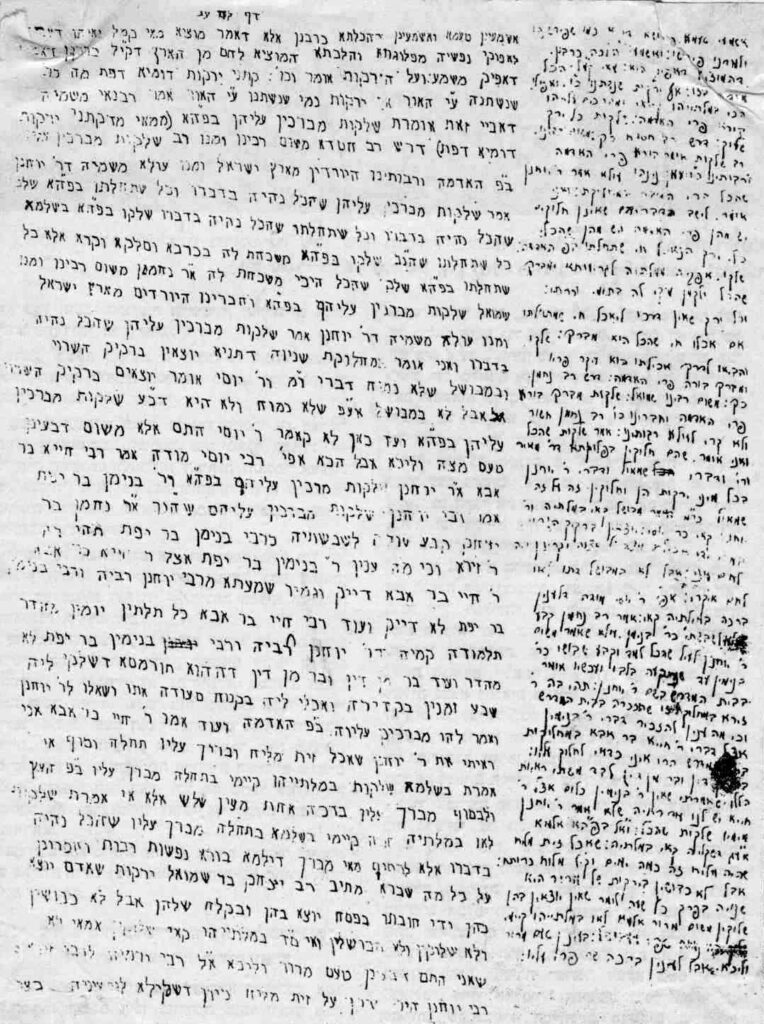

A page from Tractate Brachot that was written in a camp

The genius, the man of kindness and thoughtfulness, felt that he had run out of words. He has nothing to say. And in such a situation, when he had nothing to say, as is the norm, his face and eyelashes began to itch.

In the end, the question fell from his lips

“Hmm, Hmmmm, what do you know?“

Yaakov Tzvi was afraid of this question. And he already knew that he was not in a good situation. Tears formed in his eyes, choked his throat. An enormous bewilderment filled his heart: why?

Why is it my fault that G-d put me on a different path than all the boys here? After all, I was not negligent and I was not lazy. Only you, the blessed G-d, know how many hours I would sit with my father on cold nights in in the attic in the Lodz Ghetto and together we would devotedly study the pages of Gemara with the Rashi and Tosfot commentaries.

Silence reigned in the room and a stubborn tear rolled down Yaakov Tzvi’s cheek.

The head of the yeshiva looked into Yaakov Tzvi’s eyes and did not know his soul. He wanted to comfort, to reassure, to bless, but the insulting question came out of his mouth again: “Vos kenstu? What do you know?…“

“I know the tractates of Shabbat, Yoma, Bava Kama, Bava Metzia, and Bava Batra. By heart!” thus answered the embarassed Yaakov Tzvi. He was sure that all the young men of his age knew this very well.

And the head of the yeshiva, his eyes were round with curiosity.

These tractates are long, difficult and thorough. How does he know them “by heart”? There is not a single guy here who knows these tractates by heart. The head of the yeshiva did not believe it and began to examine Yaakov Tzvi.

And if it were said that “the head of the yeshiva was struck with astonishment” it would be an understatement compared to what was going on in the heart of the head of the yeshiva, who had already taught Torah to countless students, and yet none of them had demonstrated such proficiency in five such difficult and long tractates.

Yaakov Tzvi indeed knew all these treatises thoroughly, with wonderful proficiency and thorough understanding!

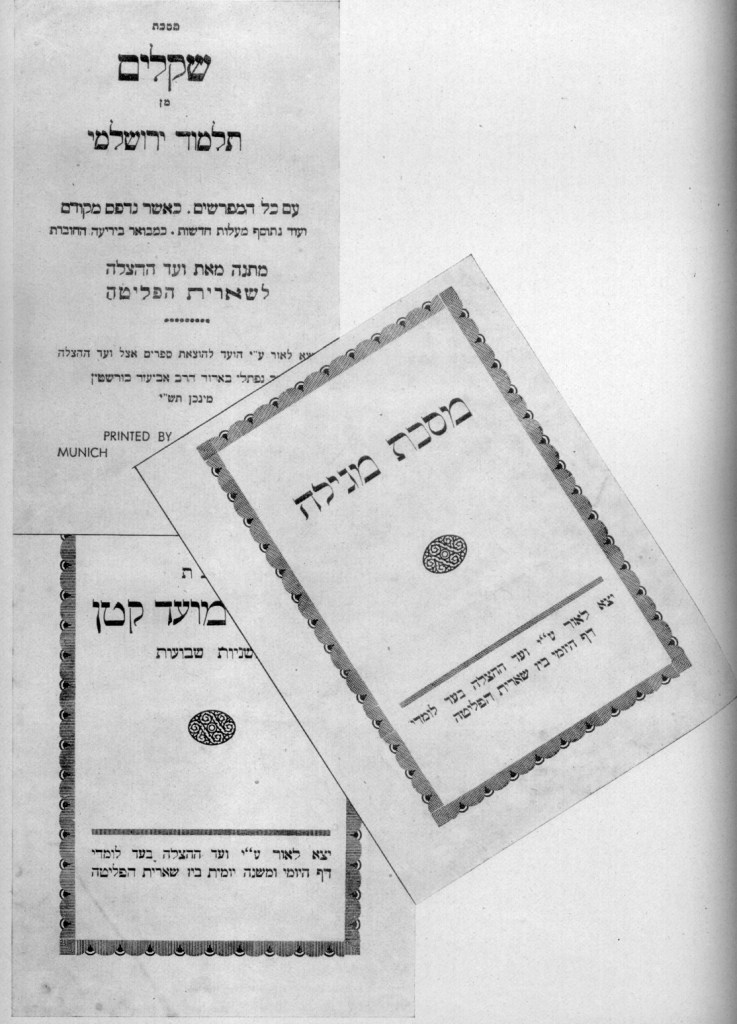

Talmudic tractates and Mishnas printed by the rabbis of the Vaad HaHatzala (Rescue Committee) in Munich

Yaakov Tzvi was accepted into the yeshiva, and grew up to be an enormous scholar. Later, when he a great rabbi, the holy Rebbe (Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky, known as the Steipler) would stand up at full height to meet him. The holy rebbe, who was almost four decades older than him, would stand up from his seat to honor him.

And when Yaakov Tzvi was 28 years old, the Steipler wrote a full letter about him full of rare expressions, which reflected the enormous appreciation that the greatest of the generation had for this young man:

Since the great man, Yaakov Tzvi, who is sharp and well-versed, marvelous in the Torah and with pure fear of G-d, had to travel abroad to be cured of the weakness of his pure body, I would like to get to know him in a place where he is not known, because a rabbi of an exalted scholar like him is precious to find, and I know him well, and he is capable to delve deeply into halacha (Jewish law) and into the depths of Torah student to fight the battle of Torah with common sense.

Written and sealed in honour of the Torah, Wednesday night, the week of the Torah portion of Chukat in 5717 (1957)

Yaakov Tzvi was humble and quiet, and he never spoke about what he went through during the horrible days and how he himself spent his days and nights in the Lodz Ghetto and then in Auschwitz. And when he was old and nearing his death, he told his beloved son the meaning of this wonderful mystery, how he knew how to be tested on five hundred and fifty pages of Gemara with the Rashi, Tosfot, and more commentaries, like the geniuses of the past.

In order to record this story, one must open the gates to the heart.

And so Yaakov Zvi, son of Avraham Chaim, told his story, and his words here should act as an upliftment of his soul there, in the place where righteous people sit with their crowns on their heads and enjoy the glory of the Shechinah (G-d’s presence).

“For five years I lived in the shadow of the Nazi beast. From the beginning of the war, I spent three years in the Lodz Ghetto, and there, every night, upon my return from the arduous forced labor, I would go up with my father to the attic and together we would sit with a few other young men and study for a few hours.”

“We didn’t have the strength, not even one drop, but out of keeping peace in our souls, we couldn’t break away from the Torah.”

“We learned pleasantly and sweetly. We knew that if we were discovered we would be killed without trial, there on the spot, but we learned anyway.”

“Out of little Gemaras we would sit and study every evening after a whole day of hard work until the end of our strength, and the hunger would torture our whole bodies, and the cold would tear us to pieces. Sometimes when we would turn on the faucet, the water would not reach the ground; it froze and shattered on the floor like stones. To this day I hear in my soul the sound of these ‘stones’ shattering on the earth.”

“For three years we studied in the Lodz Ghetto with sorrow and torment and fear of death. In these three years, we finished the tractates of Shabbat, Yoma, Bava Kama, Bava Metzia, and Bava Batra. And we repeated them over and over again and agonized over them endlessly, until when we were deported from Lodz to Auschwitz, in the year 5703 (1943), these tractates were already flesh of our flesh and bone of our bones. They were in our blood, and I already knew that I would never forget these five hundred and fifty pages, neither in this world nor in the next world.”

“I will not forget,” said Yaakov Tzvi, “that cold and gloomy night when we sat and studied together pleasantly, and suddenly we heard the oppressors enter our house, and we knew that we were lost. We heard them scream like beasts of prey, and set up a ladder to the attic where we were hiding. Our breathing stopped and we trembled with fear. We had already prepared for the worst. One of them had already touched the door handle behind which we were sitting, but a miracle happened and suddenly, for no apparent reason, the wicked turned and went downstairs, and we continued to study… and the next day we continued to study. We never stopped.”

“I studied these pages out of devotion,” said Yaakov Tzvi to his son, “and therefore they became a part of me.”

Yaakov Zvi was a boy of about eleven at the outbreak of the war, and when the wicked ones took him to Auschwitz, he was fourteen, and in Auschwitz he went through what Jews went through in Auschwitz… But he did not forget these tractates, which are about a quarter of the entire Shas (6 orders of the Mishna). They were part of his being.

And when Yaakov Tzvi told, “under one of the bushes” (Genesis 21:15), about the holy Zisman Lazerzon, may G-d avenge his blood, who had a regular study partnership with him in the ghetto, apart from the nightly study in the same ghetto, his face flushed and tears welled up in his eyes. The holy Zisman son of Avraham Yosef, may G-d avenge his blood. He was a wonderful genius and was destined to enlighten the world with his Torah and holiness, and Yaakov Tzvi studied with him several more tractates when he would manage to sneak into his house secretly and be swallowed up within its walls for more long hours of devoted Torah study.

These words should serve as an upliftment for the soul of the holy Zisman son of Avraham Yosef, who was killed by the Nazis and no trace of him remains, and for the upliftment of the soul of his study party, the genius Yaakov Tzvi son of Avraham Chaim, who was well versed in the entire Torah, and especially in the five hundred and fifty pages on which he dedicated his soul while under seige and in distress.

(Source: Rabbi Tzvi Meir Silberberg, “Kovetz Maamarei Chizuk,” 5779/2019 edition)